|

MORE INTERVIEWS WITH ALICE IN ENGLISH |

Alice Baker, American mezzosoprano and

Numerous have been her Rossini vehicles, among them Angelina in

La Cenerentola

at Gran Theāter del Liceu in Barcelona, and Rosina in

Il barbiere di Siviglia

for the Frankfurt Opera. In October/November 1997, Miss Baker returned to

the Italian stage with performances of

Candide

in the role of the Old Lady for Teatro Regio di Torino, and will open the

season at Maribor in Slovenia with

Carmen

, and role she will also sing in other houses in that country, and in Tokyo.

She recently made a special guest appearance for the closing concert of the New

Opera Festival of Rome, and in the coming months will appear in a live concert

broadcast of

Falstaff

for the Italian RAI along with the great Falstaff of our century, Giuseppe

Taddei, and colleagues Fiorenza Cossotto and Janet Perry. In fact, her concert

activity is one of her strong points: Alice Baker has passed with great

facility from

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

of Mahler to the

Ninth Symphony

of Beethoven, to the

Wesendonk Lieder

of Wagner, to Mozart's

Grand Mass in C Minor

, to

The Fairy Queen

of Purcell.

She has worked with conductors of the callibre of Carlo Maria Giulini, Giuseppe

Patanč, Sir Neville Marriner, John Nelson, Peter Maag, Sir Alexander Gibson,

Erich Leinsdorf, and Jesus Lopez-Cobos.

She has collaborated professionally with numerous directors, among them Peter

Sellars, Alberto Fassini, Beppe de Tommaso, Silvia Cassini, Luciano Pavarotti,

Pier Luigi Pizzi,and Luca Ronconi.

We met with her in the garden of her home in Rome, on a lovely sunny August

afternoon.....

OK, then, let's talk about that. What is in general, your approach to

characterization?

How important then, is the work of the director in relation to the interpreter?

maybe I am what is refered to in the acting world as a character lead---there

is a certain amount of facility, and quite frankly, I look upon this as an

advantage. It makes for freedom artistically, so many possibilities. I hope

that makes sense. I mean, I am equally happy with

Carmen

as I am with

Suzuki

, as I am with say,

Cenerentola

. Or for example, look at the roles in Handel operas. In any given opera

there might be three or four roles I could take on with equal facility. Like

in

Giulio Cesare

, for example. Since women in opera sing "trouser roles", I sing the title

role, but I also can sing Sesto, who is the son of Cornelia, the widow of

Pompeii, or as it happened most recently in Edmonton, can sing Cornelia, to

Derek Lee Ragin's

Ceasare.

They are all great roles.

great interpreter in recent years

A voice of a thousand colors

Alice Baker is one of the most interesting mezzosopranos in the musical

panorama of this last part of the century. Her credits are without a doubt

impressive considering her youth and rich collaborations with very notable

colleagues. She debuted in the opera world in 1986 singing the role of Emilia

in the opera

Otello

by Verdi in Los Angeles, flanked by Plācido Domingo. She made her first

appearance ever in Italy with Josč Carreras at Teatro dell' Opera di Roma in

the role of

Carmen

.

About a year ago I sang a production of

Madama Butterfly

in Vancouver that ended up being a very interesting experience. Out of the

ordinary

Well, I guess you would call me a singing actress, in that, not only do I try

to do absolute justice to the musical values in the score, but I also try to

bring the theatre element to life and give it equal priority. When preparing

a role, even if it is one I have sung before, I try to look for every possible

angle I can find. I research, read, meet with people, study, learn special

skills that might be required----whatever it takes to

become

the person on stage. So the role of Suzuki then, is an ideal example---to

interpret her, I try to become

her---who she is, her relationship to Butterfly, get into her mind. She is

like a sister to Butterfly, they are childhood friends, they've known each

other since they were little girls, as you see in the original Belasco play.

There is this palpable closeness between them that has taken years to evolve,

so just a look or a glance between them says a thousand words. I try to

capture that feeling, this rapport they have with one another, looking for this

same affinity with whomever may be my current Butterfly; then having found it,

it carries clear out into the house because there is truth in the expression.

The audience can feel it and so can the artists. It is this quality that makes

the performance live and become real in that moment, because there is this

feeling

between them. I try to identify with her as deeply as possible. This carries

forward obviously with Carmen, Amneris, Azucena, Preziosilla, everything. I

guess it is more in the way you approach the role, to identify to the point

of becoming.

Then, when it is there, it is true, and is completely natural and honest. It

becomes very simple and clear.

The rapport one has with the director is extremely important. I've been

exceedingly lucky to work with some of the greatest directors in the field

today, who have pulled wonderful things out of me, and am often able to throw

in ideas of my own that help define and develop the character. Obviously this

work requires at its very basis a great collaborative spirit, and a lot of

experimentation goes on, so it's exciting to combine ideas and develop things

in this way. Then of course, there's the music. The foundation of everything,

the

reason d'etre

---which logistically, in performances on stage, requires coordination in the

pit with the conductor, another artistic collaboration which is simultaneously

going on. Usually we all work together from day one, with musical readings

first, then into staging rehearsals, with the conductor present throughout.

That's great because in this work which takes place in a room before

progressing to the stage, the conductor is there too, close, as close as the

director, a very intimate way of working, so one can see all the nuances of

the phrasing, changes of tempi, etc., all perfected and integrated at the same

time as the staging is developing. You kind of have to compartmentalize your

brain a lot with this type of work---with this dual emphasis on both music and

theatre. It's fascinating and challenging. I love it.

Do you work better with opera directors or with directors with a film or

theatre background?

I really think it's more a question of communicative ability and empathy.

I've worked with directors from different backgrounds with equal success---what

matters is "buon volontā", and given that in any production, people converge

from all parts of the globe, bringing different culturals, languages, ideas,

thoughts, hopes, and dreams; it all still works because the language of theatre

and music is somehow universal, and functions regardless of the differences.

In fact, maybe that's the clue, the

differences make it more interesting.

How did you find working with Luciano Pavarotti?

Well, let's just say that when I walked into the rehearsal room for the first

read, I was scared stiff. When I walked out after that first rehearsal, I was

thinking, my God, he's just

great to work with. I mean, hear is this legend, and whenever he works, he

has a choice. He can impose his fame on a young singer, or he can be who he

is---one of the great artists of our century, yet support and inspire. And

that's what he's like. He is accessible, real, natural, simple, which just

makes him all the greater. I have had equally marvelous experiences working

with Domingo, Carreras, and Shirley Verrett, to name just a few. There's a

reason why these people are such great artists, and it has to do a lot with

what kind of human beings they are together with their art. That's a very big

part of it. So I've been extremely lucky and have learned so much by virture

of their generosity.

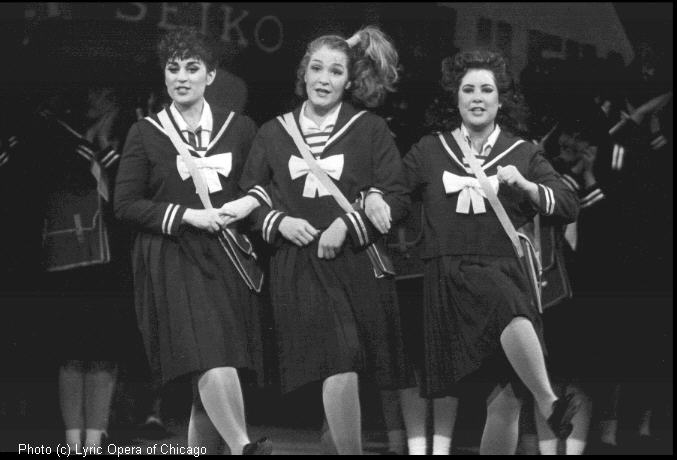

And of Peter Sellars, what do you think?

Peter is

fantastic, an endless flow of ideas. I worked

with him in a production of

The Mikado

at Lyric Opera of Chicago while an apprentice there. I was one of the "three

little maids", and we all learned to ride skateboards for the production. We

came out of an elevator singing "three little maids from school are we" with

these ghetto blasters resting on our shoulders, riding around on our

skateboards, around this big board-. room table of a major corporation in

Tokyo, e.g. the set. The audience had these little white paper covers on

their seat backs like they do on airplanes, as if they were seated on a 747

headed for Japan. Things like that, really fun. So here was this production,

obviously updated and highly original, as is his trademark. In spite of the

fact that he set it this way and it breaks all the traditonal concepts of

Gilbert and Sullivan, to me this is what theatre is all about, and should

very much be this way in opera---and I don't mean necessarily that one has to

update productions to make them fresh, but refer rather to the wealth of

creative ideas he brings to his work, and actually his concept of the piece

remains for me at least, the definitive version of the work.

What roles do you most like to interpret?

Well, I have a voice which allows me to sing a fairly wide range of repertoire

as it has size and compass, yet retains flexibility. So to answer your

question, I guess there really is no one simple answer, no particular role or

roles. I sing both leading and secondary roles and it doesn't matter a bit if

it is a so called starring role or a little role. All that matters is that it

is a

good

role and that I can find an affinity with the character. That it says

something. I think

Apropos of Rossini, do you prefer to sing from critical edition scores, or do

you like instead to follow the current trends of fioratura as evidenced by

your own colleagues?

Apropos of Rossini, do you prefer to sing from critical edition scores, or do

you like instead to follow the current trends of fioratura as evidenced by

your own colleagues?

Critical editions. Maybe because I prefer to try to get to the

essence of what the composer intended, to do justice to his work. When I sang

L'Italiana in Algeri

at the Opera in Rome, the critical edition of the opera had just come out, the

one by Bruno Cagli, and that's the one we used. It was a revelation. I had

arrived with a score from the States, and it was sadly lacking in elegance and

refinement, and of course, in places where there is some doubt as what Rossini

actually wrote, Cagli knew how to find the closest best guess ---his real

intentions. Then there are of course the copius notes and his wealth of

knowledge on the subject that he included in the edition, so there's just no

comparison. Like night and day.

So there's no real preference regarding the roles. Has there ever been a

composer whose work terrified you to learn, or at least, presented interpretive

difficulties for Alice Baker?

No, in general I don't think so, not problems of interpretation, even if at the

very beginning of my career I found myself often in the position of having

assignments given me----and with a certain apprehension on my part----on very

short notice. In St. Louis for example, I was invited to come and take over

for a countertenor who suddenly pulled out, so there I was, learning Ruggiero

in

Alcina--

nine arias on either side of recitatives, and all the da capi with all the

ornamentation to write, in only ten days before going into production. That

is what I now refer to as a

KAMAKAZI

mission. Oh, and no prompter in St. Louis, so there's nobody going to save

you if you drop a line---and in a recitativo that can be deadly. About an

hour and a half of non-stop singing to get through the role from start to

finish, then of course, everything else inbetween to know the work---any given

opera is about 350 pages of music. My mother and father have a farm in

Michigan, and I went there before going to St. Louis. There is a lane which

runs the length of the property---it takes 20 minutes to walk the length of the

lane, and I did nothing

but walk back and forth on that lane for those ten days with my headphones on,

to get that opera in my head. It was a really tough rehearsal period, the

rest of the cast having been engaged long before and all extemely well

prepared, as I would have wanted to be, and of the highest possible callibre,

the best young singers in America. So I was really under the gun the whole

time. I'd come back from staging rehearsals so

zonked,

run the tub, get in, turn on the tape and unwind while still studying,

getting everything memorzied so I could affront the next day. It all came out

just fine in the end, and that's due not only to the monumental amount of

compressed work for me that was involved, but really, because of all the help

and support I got from a great conductor and director, namely John Nelson and

Stephen Wadsworth. They coddled

me through it!

Or my debut in Rome; actually it was my European

debut. I was rehearsing for

L'Italiana in Algeri

which was to be the actual debut, and I got a call from Michele Corradi, who

was at that time the artistic director of the Theatre, at nine in the morning

(I was still in bed), asking if I would sing

Carmen

that evening with Carreras. Well I did, and it went well and it

launched

me, but let's just say that in general, I would never recommend this method.

I believe in calculated risk, but let's not exagerate. So to finally get back

to your question,

this

is the kind of thing I find really frightening. You are so young. Anyone who

strives to have a career must obviously make sacrifices,

take intelligent risks.

Do you feel like offering any advice to singers just starting out?

Yes.

Thanks for asking.

I am of the opinion that you have to have a profound passion for this work.

You have to eat, sleep, breathe, dream it, and then some. It's

necessary to arrive at and maintain the level of artistry

. You change

hats a lot, have to be flexible, open, and willing to do whatever it takes to

get there. You have to protect and

maintain the instrument---you're a vocal athelete. You need good health, you

have to take care of yourself. Otherwise it shows up in the voice and in the

quality of your work. It's hard on friends and family because you

may wish

to be normal, but you can never really be

normal

. You're traveling all the time, sometimes when they need

or want you to be around. You keep different hours than most folks. You kind

of slip through the cracks as far as day to day life is organized for most

people, especially on bea

urocratic sorts of things.

So in a way, it puts a burden on the people around you . They have to put up

with you. But the rewards and satisfaction, the sheer joy of it, and the

knowledge that you are creating something very rare and special and offering

it up to the people who see and hear you make it no sacrifice at all.

For some critics, especially our Italian critics, being too young is dangerous

for singers attempting certain roles. What do you think?

In principle, I agree, because here we are talking about vocal maturity and

vocal resources, even though a very young singer might be perfectly capable of

negotiating the dramatic demands of a given role at the outset of his or her

career, it might present problems of vocal health in the long run---what I mean

is, even though you might be able to get through the score and sing the part,

can you do it every day in a row, could you do it for years on end, can you

still do it when you have the flu, can you do it six hours a day, six days a

week while in production, and still have something left over for the

performances? And then, what kind of shape are you going to be in after the

production closes and you move on to the next city, the next climate, and the

next production? I have seen a lot of three and five year careers. It

depends on the development and

resistenza

of the voice, not just the ability to get through the role. Everyone is

different and matures at an individual rate. A light lyric soprano, for

instance, might be vocally mature at only 25 years. Heavier voices can take

much longer. I'm sure you know all that. I am for example, just now

learning Azucena, a role I have dreamed of singing for as long as I can

remember, but have waited until now. It will be, I think, about as far into

the dramatic repertoire I can safely go, I must sing her with great

intelligence and always lyrically, musically. But I think I will find a way to

do justice to the role and leave my own mark. Singing is very mental---it's

a lot about how and what you do with the resources you have. Look at Domingo

and his approach to

Otello

and how he has taken this role and made it his own. When he first sang it, I

think people were not really sure about his ability to tackle the role without

damaging himself. He sings with such intelligence. Maria Ewing has done the

same thing with Salomč. I happened to be singing another production in

repertory at the Opera in Los Angeles at the time she sang the role for the

very first time, so of course saw it, then I saw her sing it again a few

months ago, in the same production by the way, the Peter Hall production, in

the new opera house in Detroit. It was marvelous to see how she has grown in

the role and assumed so many more dimensions, and this in a span of about 10

years. Whatever the role, I remain convinced the voice must always be cared

for and used with care, never ever forced. Otherwise you run the risk of

damaging the instrument, and what good is that? Singers need to remember they

are athletes, albeit vocal athletes, and take care and train themselves like

athletes do.

Is there for you, a challenge to meet at every cost?

Yes. To be the best, artistically, and more important,

as a human being in this world. I'd like to see the opera world arrive at a

continually higher level visually---on a paar with film and theatre. I

think it's time we really did something about the situation of people starving

to death, or dying of diseases that we really could handle, or of people

not having a roof over their heads: with all the money and brains and talent

in this world, why are we still having these problems? I know we can do better

than this.

A basic education. If I ever arrive at any sort of power to effect change, I

will aim there.

I know that's a big order...but there's still an awful lot of room for

improvement.

Regarding opera,

I'd like to get rid of the stereotypical stuff that sometimes makes opera

silly and dated---get to the truth---

and fully respect the wishes and intentions of the composer. Some projects

adapt well to changing the time and setting, but others don't. I really object

when directors who don't speak the langauge of the libretto fluently, or didn't

do their homework ask singers to enact scenes which have absolutely no relation

to the text which they are singing at that moment. If you're smart and good at

what you do, you can find a way to do it and still remain "fedele" to the text.

Same goes with the music.

A lot of opera today looks like the silent movies of

the first decade of the century---it must be great theatre and great music or

it will never work, otherwise it weakens the whole structure instead of making

it stronger, it's distracting, and takes away from the greatness of the art

form. I'd like to see arias, for instance on MTV, like music videos. With

the right director and production values they'd be just fantastic. I'd like to

see more well-made films of opera, produced realistically...I could go on and

on.....

On to Productions Main Page

On to Photo Galleries

Back to

Alice's Home Page

||The Story behind

the Face||

So, what's it like at the Office? ||

||

A little Humour, perhaps? ||

Kidstuff...||

Backstage fun...||

||

Interviews with Alice||

CD: Pergolesi's Stabat Mater ||

||

Ok, so how did all this silly stuff start, anyway? Opera Singer FAQ ||

||

The Cats of Rome||

||

Press

Quotes in English||

Biography

for Alice ||

||

Contact info for Alice || Or, E-mail Alice directly here ||

Back

to the Top||

CMI Arts

Copyright Š 2000 - 2003 CMI Arts. All rights reserved.