It's difficult to understand Sicily without knowing its history, which sunk in the fog of prehistory and myth.

The Hellenic invasions | The Norman conquest | Modern Sicily

HISTORY

It's difficult to understand Sicily without knowing its history, which sunk in the fog of prehistory and myth.

The Hellenic invasions | The Norman conquest | Modern Sicily

The

story of Sicily reflects the story of mankind in the Mediterranean, from the

first evidence of the human ability to think, to the current problems of Europe. The

oldest remains are the cave paintings in the Addaura Caves on Monte Pellegrino

north of Palermo, reputed to be around 10000 years old. There are remains of

a prehistoric village on Panarea, one of Lipari Island.

evidence of the human ability to think, to the current problems of Europe. The

oldest remains are the cave paintings in the Addaura Caves on Monte Pellegrino

north of Palermo, reputed to be around 10000 years old. There are remains of

a prehistoric village on Panarea, one of Lipari Island.

About 700 BC Semitic Carthaginians from north Africa established colonies

on Sicily, but it was the Greek, those consummate sailors endlessly curios about

the world around them, who brought civilization to the island. Countiously feeling

their way westward towards the Pillars of Hercules and the vast Atlantic Ocean

beyond, they encountered the island. Some continued north, braving the terrors

of the monster Scylla and Charybdis (whirlpools and rocks in the Strait of Messina),

to the coast of mainland Italy where they settled, but most were content to

settle on the amazingly fertile eastern and southern coasts of the island, gradually

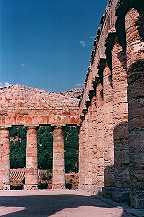

spreading out all around the coast. The Greek remains on Sicily today probably

outclass in quantity, if not in quality, the remains on mainland Greece. The

Greek brought civilization but certainly not peace, importing instead the jealousies

and hatreds between cities that were part of Greek mainland culture. The city

of Corinth, deadly enemy of Athens, founded the city of Syracuse on the eastern

coast, which prospered amazingly.

About 700 BC Semitic Carthaginians from north Africa established colonies

on Sicily, but it was the Greek, those consummate sailors endlessly curios about

the world around them, who brought civilization to the island. Countiously feeling

their way westward towards the Pillars of Hercules and the vast Atlantic Ocean

beyond, they encountered the island. Some continued north, braving the terrors

of the monster Scylla and Charybdis (whirlpools and rocks in the Strait of Messina),

to the coast of mainland Italy where they settled, but most were content to

settle on the amazingly fertile eastern and southern coasts of the island, gradually

spreading out all around the coast. The Greek remains on Sicily today probably

outclass in quantity, if not in quality, the remains on mainland Greece. The

Greek brought civilization but certainly not peace, importing instead the jealousies

and hatreds between cities that were part of Greek mainland culture. The city

of Corinth, deadly enemy of Athens, founded the city of Syracuse on the eastern

coast, which prospered amazingly. Alarmed by the growing power of the Tyrant of Syracuse, as the ruler was known,

Athens dispatched an immense fleet, but it was totally defeated and some 7000

Athenians finished up as slaves in the quarries of Syracuse.

Alarmed by the growing power of the Tyrant of Syracuse, as the ruler was known,

Athens dispatched an immense fleet, but it was totally defeated and some 7000

Athenians finished up as slaves in the quarries of Syracuse.![]()

All the previous conquerors

of Sicily had at least shared a common Mediterranean background, but the Normans

came like a thunderbolt from the north, led by two brothers, Robert and Roger

de Hauteville, who had already worked their way down the length of Italy. They

crossed the Strait of Messina in strength in 1061 (just five years before their

fellow Normans crossed the English Channel for the conquest of England) and,

after some 30 years of bitter fighting, eventually dominated all Sicily. They

established a monarchy with the capital in Palermo, which endured, under five

successive kings, until the last decade of the 12C.

All the previous conquerors

of Sicily had at least shared a common Mediterranean background, but the Normans

came like a thunderbolt from the north, led by two brothers, Robert and Roger

de Hauteville, who had already worked their way down the length of Italy. They

crossed the Strait of Messina in strength in 1061 (just five years before their

fellow Normans crossed the English Channel for the conquest of England) and,

after some 30 years of bitter fighting, eventually dominated all Sicily. They

established a monarchy with the capital in Palermo, which endured, under five

successive kings, until the last decade of the 12C. A multi-talented man centuries in advance of his time, running his essentially

Germanic empire from this outpost in the Mediterranean, he earned for himself the sobriquet

Stupor Mundi (The Wonder of the World). He clashed with the Pope and was excommunicated. After his death in 1250 legend told how he was seen

riding at the head of a vast army into the mouth of Etna.

A multi-talented man centuries in advance of his time, running his essentially

Germanic empire from this outpost in the Mediterranean, he earned for himself the sobriquet

Stupor Mundi (The Wonder of the World). He clashed with the Pope and was excommunicated. After his death in 1250 legend told how he was seen

riding at the head of a vast army into the mouth of Etna.![]()

In the 1920s and 1930s Mussolini's decree that the Mediterranean was Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), together with his African adventures,

brought Sicily again into mainland politics. The island suffered badly in the

Second World War, when the Allies used it as a springboard to enter Italy from

Africa. The immediate post-war years were a time of confusion and feuding with

considerable violence, in which the Mafia played a leading

role. In

1946 the island was granted regional autonomy its own president and parliament

but, along with the rest of the Mezzogiorno (Italy south of Rome) gained

relatively little from Italy's economic progress. Although Sicilians still emigrate

in their thousands, land reform, the determined attack upon organized crime

and a burgeoning tourist industry all give hope for the future.

Mediterranean was Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), together with his African adventures,

brought Sicily again into mainland politics. The island suffered badly in the

Second World War, when the Allies used it as a springboard to enter Italy from

Africa. The immediate post-war years were a time of confusion and feuding with

considerable violence, in which the Mafia played a leading

role. In

1946 the island was granted regional autonomy its own president and parliament

but, along with the rest of the Mezzogiorno (Italy south of Rome) gained

relatively little from Italy's economic progress. Although Sicilians still emigrate

in their thousands, land reform, the determined attack upon organized crime

and a burgeoning tourist industry all give hope for the future.![]()