BALUNS AND COAXIAL AERIALS

If you are dealing with radiofrequency

aerials you might like to experiment with the configurations proposed.

In fig. 1 there is a balun which transforms an unbalanced line into a

balanced feed. You need to connect a variable capacitor, typically a

trimmer capacitor, between two points on the braid of the terminal part

of the coaxial cable as shown in the drawing. The length and the

capacitor value are optimized for operation in the Citizen Band and 50Ω cable but the set up is not critical

at all and should work at other frequencies as well. The advantage of

this balun is that you can provide a perfectly balanced feed to the

aerial thus compensating for any unbalance introduced by the topography

of the ground around the same aerial. Another interesting application

for this balun is to use it as a power splitter: if you measure the

output power relative to ground (i.e. the cold side of the capacitor),

you may adjust the power fed to the two terminals by simply operating on

the capacitor. The phase relationship has not been investigated. Fig. 2

is a more classical approach to the problem: two quarter wavelength

sections of the same coaxial cable give a balanced output with the least

of trouble, but it must be mentioned that it works well only around the

designed frequency, it is not a wideband balun. Length l is equal to (λ/4)xP

where λ

is the operating wavelength and P is the propagation

factor which depends on the type of dielectric material used in the

coaxial cable as shown in the table:

If you are dealing with radiofrequency

aerials you might like to experiment with the configurations proposed.

In fig. 1 there is a balun which transforms an unbalanced line into a

balanced feed. You need to connect a variable capacitor, typically a

trimmer capacitor, between two points on the braid of the terminal part

of the coaxial cable as shown in the drawing. The length and the

capacitor value are optimized for operation in the Citizen Band and 50Ω cable but the set up is not critical

at all and should work at other frequencies as well. The advantage of

this balun is that you can provide a perfectly balanced feed to the

aerial thus compensating for any unbalance introduced by the topography

of the ground around the same aerial. Another interesting application

for this balun is to use it as a power splitter: if you measure the

output power relative to ground (i.e. the cold side of the capacitor),

you may adjust the power fed to the two terminals by simply operating on

the capacitor. The phase relationship has not been investigated. Fig. 2

is a more classical approach to the problem: two quarter wavelength

sections of the same coaxial cable give a balanced output with the least

of trouble, but it must be mentioned that it works well only around the

designed frequency, it is not a wideband balun. Length l is equal to (λ/4)xP

where λ

is the operating wavelength and P is the propagation

factor which depends on the type of dielectric material used in the

coaxial cable as shown in the table:

|

Dielectric |

P |

Typical Cable |

|

Solid polyethylene |

0.665 |

RG 58 / RG 11 |

|

Polyethylene/air |

0.835 |

RG 62 / RG 79 |

|

Fluorocarbon (Teflon) |

0.675 |

RG 94 / RG 209 |

|

Foam polyethylene |

0.816 |

TV cable |

The balun in fig. 2 can

be wired also as in fig. 3. In fact, points A and B are at the same

potential and can be connected together. Nothing changes from the

electrical point of view but it can make a more compact construction in

certain circumstances. The first application will allow you to install a

CB car aerial in any other place without the need of the metal body of

the car (fig. 4). The vertical section of the coaxial cable is

short-circuited at the lower end. You might need to adjust the length of

the whip, once in its final place, because distance d is to be

subtracted from the total length of the car aerial.

The balun in fig. 2 can

be wired also as in fig. 3. In fact, points A and B are at the same

potential and can be connected together. Nothing changes from the

electrical point of view but it can make a more compact construction in

certain circumstances. The first application will allow you to install a

CB car aerial in any other place without the need of the metal body of

the car (fig. 4). The vertical section of the coaxial cable is

short-circuited at the lower end. You might need to adjust the length of

the whip, once in its final place, because distance d is to be

subtracted from the total length of the car aerial.

The typical application is shown in fig. 5. Two different lengths are given: one applies to 50Ω cables and baluns and the other applies to 75Ω cables and baluns (fig. 7), these values are good for the design of receiving FM or TV aerials right up to UHF. It must be said that these designs are narrow band aerials and are not suitable to cover a wide frequency range. This means that if you tune to a specific TV channel you will get a performance that could be better than a Yagi but gives poor results at other channels. One way around is to purposefully mismatch the design in order to cover a wider range but I was unable to assess how good this solution was.

If you find that the aerial is too long at

the working frequency, you could apply the design of fig. 6 where a coil

is inserted at the base of the aerial. The coil is made with 17 turns of

2mm electric wire on a 17mm form. These data are valid for the 27Mhz

band and must be properly scaled at other frequencies. In all cases the

vertical coax must be shorted at the far end because it works also as an

impedance matcher for the rest of the aerial. Installation can be

vertical, as shown in the drawings, or horizontal.

If you find that the aerial is too long at

the working frequency, you could apply the design of fig. 6 where a coil

is inserted at the base of the aerial. The coil is made with 17 turns of

2mm electric wire on a 17mm form. These data are valid for the 27Mhz

band and must be properly scaled at other frequencies. In all cases the

vertical coax must be shorted at the far end because it works also as an

impedance matcher for the rest of the aerial. Installation can be

vertical, as shown in the drawings, or horizontal.

All the mentioned aerials were tested in the 27Mhz band with satisfactory results: best performance being from the design of fig. 5. Gain was measured between 6 and 9 dB but the instrument available was not very accurate and I cannot bet on the number reported. As a receiving aerial it was tested in the FM range, VHF and UHF: in the VHF range I could see a TV channel that I was unable to see with a 4 element Yagi; in the UHF range the mechanical construction is rather critical due to the small size and the need of a wideband aerial becomes a major drawback.

SINGLE LED FLASHER

Flashing a LED should

not require a complex circuit. A reverse biased transistor does the job

in a nice way. Circuit "a" flashes the LED twice a second:

changing the capacitor and/or the resistor will change the frequency,

also the supply voltage will influence its frequency of operation. A

BC337 can be used instead of the 2N2222A; in this case the supply

voltage can be lowered to 9V. Circuit "b" gives the same result

but it will work directly off the mains, so be careful with the live

wire because it can be a hazard if you do not take all necessary

precautions. If the mains voltage is 110VAC the resistor should be

decreased from 100K to 47K. If a BC337 is used, then the resistor is

390K for a 220V mains and 180K for a 110V mains. The zener is not

required for its operation: it is only a safety measure that avoids

voltage build up if the LED gets disconnected. When you reconnect it,

the current surge will destroy the transistor and the LED. The capacitor

could be damaged as well. Both circuits will work with all coloured led

but circuit "a"

will require a 2V higher supply

voltage if you use white or blue led.

Flashing a LED should

not require a complex circuit. A reverse biased transistor does the job

in a nice way. Circuit "a" flashes the LED twice a second:

changing the capacitor and/or the resistor will change the frequency,

also the supply voltage will influence its frequency of operation. A

BC337 can be used instead of the 2N2222A; in this case the supply

voltage can be lowered to 9V. Circuit "b" gives the same result

but it will work directly off the mains, so be careful with the live

wire because it can be a hazard if you do not take all necessary

precautions. If the mains voltage is 110VAC the resistor should be

decreased from 100K to 47K. If a BC337 is used, then the resistor is

390K for a 220V mains and 180K for a 110V mains. The zener is not

required for its operation: it is only a safety measure that avoids

voltage build up if the LED gets disconnected. When you reconnect it,

the current surge will destroy the transistor and the LED. The capacitor

could be damaged as well. Both circuits will work with all coloured led

but circuit "a"

will require a 2V higher supply

voltage if you use white or blue led.

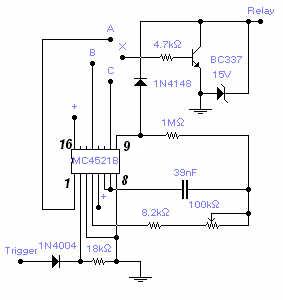

LONG DELAY TIMER

A max.

delay of 20 hours is achieved by this relatively simple circuit. A

permanent ground, or no signal, at the trigger input starts the timer. A

ground at the relay output is available after a set time that depends on

the connection of the transistor base (X) to one of the counter output:

connection with (C) gives a min. delay of 1m 40s and max. of 18m 30s.

Connection with (B) gives a min. delay of 13m 20s and max. of 2h 28m.

Connection with (A) gives a min. delay of 1h 47m and max. of 20h. Supply

voltage is between 6 and 15V and longer delay could be obtained by

increasing the capacitor value up to 10 times with a delay in excess of

1 week. A positive at the trigger input will reset the counter. Adjust

the 100K pot. for the desired timing. The load is typically a relay but

any load with a max. current of 200 mA will work fine. Admittedly this

is not a very original circuit but can save some time if you need to

build one. The IC is a Cmos 24-stage binary counter MC4521B from

Fairchild, or alternatively, you may use the MC14521B from Motorola.

A max.

delay of 20 hours is achieved by this relatively simple circuit. A

permanent ground, or no signal, at the trigger input starts the timer. A

ground at the relay output is available after a set time that depends on

the connection of the transistor base (X) to one of the counter output:

connection with (C) gives a min. delay of 1m 40s and max. of 18m 30s.

Connection with (B) gives a min. delay of 13m 20s and max. of 2h 28m.

Connection with (A) gives a min. delay of 1h 47m and max. of 20h. Supply

voltage is between 6 and 15V and longer delay could be obtained by

increasing the capacitor value up to 10 times with a delay in excess of

1 week. A positive at the trigger input will reset the counter. Adjust

the 100K pot. for the desired timing. The load is typically a relay but

any load with a max. current of 200 mA will work fine. Admittedly this

is not a very original circuit but can save some time if you need to

build one. The IC is a Cmos 24-stage binary counter MC4521B from

Fairchild, or alternatively, you may use the MC14521B from Motorola.

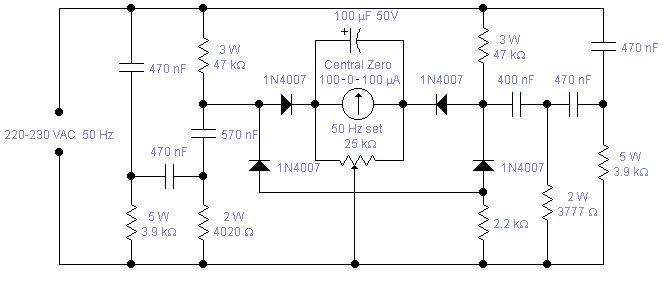

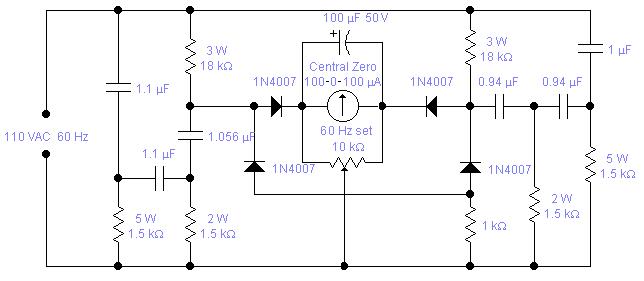

MAINS FREQUENCY METER

Mains

frequency is pretty stable and it is unlikely that you have to measure

it but if you have an emergency generator you might find this circuit

useful as it will give an indication whether the generator is running

too fast or too slow. Actually you can use the mains frequency to

calibrate it by adjusting the 25K multiturn trimmer until it reads 0.

The odd looking components values are easily obtained using standard

values: 3777 is 3900 in parallel with 120KΩ,

4020 is 3900 and 120 in series, 570nF is 470nF with 100nF in parallel

and 400nF is 4 x 100nF capacitors in parallel. Components should be

chosen for their stability and precision. 1% tolerance would be ideal

but 5% is acceptable so long as you measure them with a good meter.

Capacitors should be properly rated for direct connection to the mains

and resistors should have a low temperature coefficient as it will

adversely affect the zero setting and change the filters response. The

100μF capacitor could be

occasionally reverse biased with a voltage of 0.1-0.2 V. There is no

problem for the capacitor which is generously rated. Operation is quite

simple: connect it first to the mains, wait about 4-5 minutes until all

resistors reach their working temperature, calibrate, and then connect

to the generator. Variation in the mains voltage will not change the

zero setting but will make the meter more or less sensitive: for

example, a reading of 51 Hz will show as 51.1 with a 10% supply voltage

increase.

Mains

frequency is pretty stable and it is unlikely that you have to measure

it but if you have an emergency generator you might find this circuit

useful as it will give an indication whether the generator is running

too fast or too slow. Actually you can use the mains frequency to

calibrate it by adjusting the 25K multiturn trimmer until it reads 0.

The odd looking components values are easily obtained using standard

values: 3777 is 3900 in parallel with 120KΩ,

4020 is 3900 and 120 in series, 570nF is 470nF with 100nF in parallel

and 400nF is 4 x 100nF capacitors in parallel. Components should be

chosen for their stability and precision. 1% tolerance would be ideal

but 5% is acceptable so long as you measure them with a good meter.

Capacitors should be properly rated for direct connection to the mains

and resistors should have a low temperature coefficient as it will

adversely affect the zero setting and change the filters response. The

100μF capacitor could be

occasionally reverse biased with a voltage of 0.1-0.2 V. There is no

problem for the capacitor which is generously rated. Operation is quite

simple: connect it first to the mains, wait about 4-5 minutes until all

resistors reach their working temperature, calibrate, and then connect

to the generator. Variation in the mains voltage will not change the

zero setting but will make the meter more or less sensitive: for

example, a reading of 51 Hz will show as 51.1 with a 10% supply voltage

increase. Full scale deflection is around +/- 2 Hz. If

you wish to accommodate a wider range of +/- 3.5 Hz, typical for a

petrol driven generator, you have to change the 2.2KΩ

resistor to 12KΩ.

Full scale deflection is around +/- 2 Hz. If

you wish to accommodate a wider range of +/- 3.5 Hz, typical for a

petrol driven generator, you have to change the 2.2KΩ

resistor to 12KΩ.

WARNING! This circuit is directly connected to the mains and should be assembled in a box which will avoid access to any of its part and care must be exercised when calibrating the unit. If you live in the States or you have a 110 VAC, 60 Hz mains, you may try the second circuit: the reported values are calculated values, I did not actually test the unit. The odd capacitors values are easily obtained with the combination of standard values: 0.94 is 2 x 0.47 in parallel, 1.056 is 1μF + 56nF in parallel and 1.1 is 1 + 0.1μF.

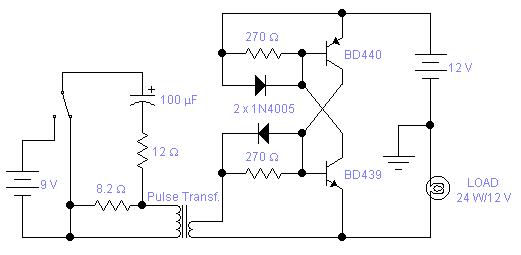

ELECTRONIC RELAY

In some

applications where you require speed of operation and no contact

bouncing, you may find this circuit helpful. This is really the

implementation of an SCR with discrete components. The medium power

complementary pair will switch on and off a load up to 3A. You may

modify the circuit to carry up to 10A using suitable power transistors

and diodes. The left side of the circuit shows a typical drive. This

electronic relay will latch in the on or off position depending on the

direction of the pulse going through the primary winding of the

transformer. You may omit the capacitor altogether; in this case the

circuit behaves very much like the coil of a relay: when you apply a

voltage to the primary it will switch on and when you remove the voltage

it will switch off. The drawback in this second case is that there is a

large amount of power dissipated in the 12Ω

resistor which must be rated accordingly. The pulse transformer is

recovered from a faulty electronic neon light. The drive circuit for

these lamps always includes a pulse transformer. The higher impedance,

or resistance, is the primary and the other winding is the secondary.

The measured resistance was below 0.4Ω and the

inductance was 680 and 47μH for the

primary and secondary respectively. The ideal would be a pulse

transformer with two secondary windings so that both transistors could

be driven but you have the same results if the drive is applied to one

transistor only. The circuit has its limitations: there is a voltage

drop across the switch, in the on state, between 0.7 and 1V, this may

not be acceptable in low voltage applications; it will work only with DC

supplies and there is a minimum sustain current, 12mA in the circuit

shown. Below this current the switch will revert to its off state. You

may, of course, design a circuit with low power transistors with a

sustain current of only a few μA if

necessary.

In some

applications where you require speed of operation and no contact

bouncing, you may find this circuit helpful. This is really the

implementation of an SCR with discrete components. The medium power

complementary pair will switch on and off a load up to 3A. You may

modify the circuit to carry up to 10A using suitable power transistors

and diodes. The left side of the circuit shows a typical drive. This

electronic relay will latch in the on or off position depending on the

direction of the pulse going through the primary winding of the

transformer. You may omit the capacitor altogether; in this case the

circuit behaves very much like the coil of a relay: when you apply a

voltage to the primary it will switch on and when you remove the voltage

it will switch off. The drawback in this second case is that there is a

large amount of power dissipated in the 12Ω

resistor which must be rated accordingly. The pulse transformer is

recovered from a faulty electronic neon light. The drive circuit for

these lamps always includes a pulse transformer. The higher impedance,

or resistance, is the primary and the other winding is the secondary.

The measured resistance was below 0.4Ω and the

inductance was 680 and 47μH for the

primary and secondary respectively. The ideal would be a pulse

transformer with two secondary windings so that both transistors could

be driven but you have the same results if the drive is applied to one

transistor only. The circuit has its limitations: there is a voltage

drop across the switch, in the on state, between 0.7 and 1V, this may

not be acceptable in low voltage applications; it will work only with DC

supplies and there is a minimum sustain current, 12mA in the circuit

shown. Below this current the switch will revert to its off state. You

may, of course, design a circuit with low power transistors with a

sustain current of only a few μA if

necessary.

In order to

generate a single note you may try these simple circuits. With only

three components you may implement some basic buzzers. You need a

telephone earpiece for the first circuit. Any old telephone set has got

one of those magnetic earpiece that is right for our purposes. Add an

extra capacitor and a transistor and you have your buzzer. Frequency of

operation is about 1800 Hz and the capacitor must be changed if you wish

to have a different frequency. The second circuit is implemented with a

ceramic sounder: its intrinsic capacity is used to make another simple

buzzer. Working frequency is 800 Hz and power drain is really low. The

operating voltage is 9.5 - 20V for the circuit with the ceramic sounder

and 8 - 16V for the other circuit. Do not expect a loud sound level: it

is rather limited just as the current drain is. These buzzers are

suitable for audio signaling on portable devices and wherever it is

necessary to have a sound source implemented with a minimum components

count. Not all transistors will oscillate: you have to use the specified

type although I found that the BC109 and 2N2222A will also work albeit

at a slightly different voltage.

In order to

generate a single note you may try these simple circuits. With only

three components you may implement some basic buzzers. You need a

telephone earpiece for the first circuit. Any old telephone set has got

one of those magnetic earpiece that is right for our purposes. Add an

extra capacitor and a transistor and you have your buzzer. Frequency of

operation is about 1800 Hz and the capacitor must be changed if you wish

to have a different frequency. The second circuit is implemented with a

ceramic sounder: its intrinsic capacity is used to make another simple

buzzer. Working frequency is 800 Hz and power drain is really low. The

operating voltage is 9.5 - 20V for the circuit with the ceramic sounder

and 8 - 16V for the other circuit. Do not expect a loud sound level: it

is rather limited just as the current drain is. These buzzers are

suitable for audio signaling on portable devices and wherever it is

necessary to have a sound source implemented with a minimum components

count. Not all transistors will oscillate: you have to use the specified

type although I found that the BC109 and 2N2222A will also work albeit

at a slightly different voltage.

![]() Eager for more

Eager for more  Full astern to main page

Full astern to main page

![]()