|

PICCOLE STORIE - DIARI MINIMI

|

'The War in

Italy'

(August,

1916)

By H.G. Wells (Bromley, 21 settembre 1866 – Londra, 13

agosto 1946)

Herbert George Wells nasce in Inghilterra da una

famiglia di umili condizioni. Entra alla Normal School of Science di

Londra dove, dopo aver svolto molti lavoretti per mantenersi, studia biologia sotto il Prof. T.H. Huxley. Dal 1893 inizia a

vendere regolarmente racconti ed articoli di fantascienza. Famoso rimase

l'adattamento radiofonico de "La guerra dei mondi" che Orson Welles (1938)

fece alla radio come una radiocronaca in diretta. Chi non aveva seguito la

presentazione credette che la Terra stesse realmente subendo lo sbarco

d'una bellicosa flotta d'astronavi marziane. Sulla Costa orientale degli

U.S.A. si scatenò il panico.

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._G._Wells

War

and the Future - Guerra e Futuro |

|

|

Per chi ama le montagne

http://www.summitpost.org/user_page.php?user_id=17266

"Deve essere stato come prendere

d'assalto il cielo." H. G. Wells

Behind the Front - 2a parte -

della 1a parte Guerra in Montagna

http://www.frontedolomitico.it/Testimonianze/FronteDolomiticoWells.htm

open library

http://www.archive.org/details/warandfutureital00welluoft

I HAVE a peculiar affection for Verona and certain things in Verona. Italians

must forgive us English this little streak of impertinent proprietorship in the

beautiful things of their abundant land. It is quite open to them to revenge

themselves by professing a tenderness for Liverpool or Leeds. It was, for

instance, with a peculiar and personal indignation that I saw where an Austrian

air bomb had killed five-and-thirty people in the Piazza Erbe. Somehow in that

jolly old place, a place that have very much of the quality of a very pretty and

cheerful old woman, it seemed exceptionally an outrage. And I made a special

pilgrimage to see how it was with that monument of Can Grande, the equestrian

Scaliger with the sidelong grin, for whom I confess a ridiculous admiration. Can

Grande, I rejoice to say, has retired into a case of brickwork, surmounted by a

steep roof of thick iron plates; no aeroplane exists to carry bombs enough to

smash that covering; there he will smile securely in the darkness until peace

comes again.

Piccola traduzione del paragrafo sovrastante: Ho un amore particolare per Verona,.. e sono

estremamente indignato nel vedere il punto dove in Piazza delle Erbe una bomba

austriaca ha ucciso 35 persone. E lo sono ancora di più nel vedere il Can Grande

a cavallo ridotto in una trincea di mattoni sormontati da lastre di ferro

All over Venetia the Austrian seaplanes are making the same sort of idiot raid

on lighted places that the Zeppelins have been making over England. These raids

do no effective military work. What conceivable military advantage can there be

in dropping bombs into a marketing crowd? It is a sort of anti-Teutonic

propaganda by the Central Powers to which they seem to have been incited by

their own evil genius. It is as if they could convince us that there is an

essential malignity in Germans, that until the German powers are stamped down

into the mud they will continue to do evil things. All of the Allies have borne

the thrusting and boasting of Germany with exemplary patience for half a century;

England gave her Heligoland and stood out of the way of her colonial expansion,

Italy was a happy hunting ground for her business enterprise, France had come

near resignation on the score of Alsace-Lorraine. And then over and above the

great outrage of the war come these incessant mean-spirited atrocities. A great

and simple wickedness it is possible to forgive; the war itself, had it been

fought greatly by Austria and Germany, would have made no such deep and enduring

breach as these silly, futile assassinations have down between the

Austro-Germans and the rest of the civilised world. One great misdeed is a thing

understandable and forgivable; what grows upon the consciousness of the world is

the persuasion that here we fight not a national sin but a national insanity;

that we dare not leave the German the power to attack other nations any more for

ever All over Venetia the Austrian seaplanes are making the same sort of idiot raid

on lighted places that the Zeppelins have been making over England. These raids

do no effective military work. What conceivable military advantage can there be

in dropping bombs into a marketing crowd? It is a sort of anti-Teutonic

propaganda by the Central Powers to which they seem to have been incited by

their own evil genius. It is as if they could convince us that there is an

essential malignity in Germans, that until the German powers are stamped down

into the mud they will continue to do evil things. All of the Allies have borne

the thrusting and boasting of Germany with exemplary patience for half a century;

England gave her Heligoland and stood out of the way of her colonial expansion,

Italy was a happy hunting ground for her business enterprise, France had come

near resignation on the score of Alsace-Lorraine. And then over and above the

great outrage of the war come these incessant mean-spirited atrocities. A great

and simple wickedness it is possible to forgive; the war itself, had it been

fought greatly by Austria and Germany, would have made no such deep and enduring

breach as these silly, futile assassinations have down between the

Austro-Germans and the rest of the civilised world. One great misdeed is a thing

understandable and forgivable; what grows upon the consciousness of the world is

the persuasion that here we fight not a national sin but a national insanity;

that we dare not leave the German the power to attack other nations any more for

ever

Piccola traduzione ..: anche sopra Venezia si fanno simili azioni le stesse che gli

zeppelin fanno sopra il mio paese. Questi raid non hanno alcunché di strategico.

Quale mente diabolica può pensare a vantaggi bombardando un mercato. Tutti gli

alleati hanno tollerato per cinquant'anni e dato come noi Helgoland o la Francia

L'Alsazia e Lorena.

Venice has

suffered particularly from this ape-like impulse to hurt and

terrorise enemy non-combatants. Venice has indeed suffered from this war far

more than any other town in Italy. Her trade has largely ceased; she has no

visitors. I woke up on my way to Udine and found my train at Venice with an hour

to spare; after much examining and stamping of my passport I was allowed outside

the station wicket to get coffee in the refreshment room and a glimpse of a very

sad and silent Grand Canal. There was nothing doing; a black despondent remnant

of the old crowd of gondolas browsed dreamily among against the quay to stare at

me the better. The empty palaces seemed to be sleeping in the morning sunshine

because it was not worth while to wake up. . . .

Venezia ha sofferto più di ogni altra città. Non ci sono più turisti, non c'è

più commercio. Mi ci sono fermato nell'andare ad Udine e dopo timbri e controlli

in un'ora di tempo fra un treno e l'altro ho potuto uscire dalla stazione

(vecchia asburgica) e prendere un caffè sul Canalgrande.

Except in the case of Venice, the war does not seem as yet to have made nearly

such a mark upon life in Italy as it has in England or provincial France.

People speak of Italy

as a poor country, but that is from a banker’s point of view. In

some respects she is the richest country on earth, and in the matter of staying

power I should think she is better off than any other belligerent. She produces

food in abundance everywhere; her women are agricultural workers, so that the

interruption of food production by the war has been less serious in Italy than

in any other part of Europe. In peace time, she has constantly exported labour;

the Italian worker has been a seasonal emigrant to America, north and south, to

Switzerland, Germany and the south of France. The cessation of this emigration

has given her great reserves of man power, so that she has carried on her

admirable campaign with less interference with her normal economic life than any

other power. The first person I spoke to upon the platform at Modane was a

British officer engaged in forwarding Italian potatoes to the British front in

France. Afterwards, on my return, when a little passport irregularity kept me

for half a day in Modane, I went for a walk with him along the winding pass road

that goes down into France. “You see hundreds and hundreds of new Fiat cars,” he

remarked, “along here—going up to the French front.”

La gente parla dell'Italia come d'un paese povero, ma questo è un punto di vista

dei banchieri. Sotto certi aspetti questo è il paese più ricco del mondo.

Produce cibo e i suoi abitanti, in special modo le donne sono nati agricoltori.

Con gli uomini che stagionalmente emigravano, ora non risentono di conseguenze

perchè sono al fronte. Anzi si può dire che ha danneggiato chi importava mano

d'opera. Ho parlato con un ufficiale inglese che provvedeva i suoi sul fronte

francese con patate Italiane e a Modane (dogana Francese) si vedono passare

centinaia di automezzi Fiat per il fronte francese

But there is a return trade. Near Paris I saw scores of thousands of shells

piled high to go to Italy. . . . But there is a return trade. Near Paris I saw scores of thousands of shells

piled high to go to Italy. . . .

I doubt if English people fully realise either the economic sturdiness or the

political courage of their Italian ally. Italy is not merely fighting a

first-class war in first-class fashion but she is doing a big, dangerous,

generous and far-sighted thing in fighting at all.

France and England

were

obliged to fight; the necessity was as plain as daylight. The participation of

Italy demanded a remoter wisdom. In the long run she would have been swallowed

up economically and politically by Germany if she had not fought; but that was

not a thing staring her plainly in the face as the danger, insult and challenge

stared France and England in the face. What did stare her in the face was not

merely a considerable military and political risk, but the rupture of very close

financial and commercial ties. I found thoughtful men talking everywhere I have

been in Italy of two things, of the Jugo-Slav riddle and of the question of post

war finance. So far as the former matter goes, I think the Italians are set upon

the righteous solution of all such riddles, they are possessed by an intelligent

generosity. They are clearly set upon deserving Jugo-Slav friendship; they

understand the plain necessity of open and friendly routes towards Roumania. It

was an Italian who set out to explain to me that Fiume must be at least a free

port; it would be wrong and foolish to cut the trade of Hungary off from the

Mediterranean. But the banking puzzle is a more intricate and puzzling matter

altogether than the possibility of trouble between Italian and Jugo-Slav.

Francia e Inghilterra sono obbligate a combattere gli italiani no. In Italia si

parla di due cose: dei rapporti con la futura Jugoslavia, dei confini orientali

e delle sponde dell'adriatico e dei debiti postbellici per gli armamenti. La

generosità del paese penso però che risolverà tutto. Me lo ha detto un

italiano che alla fine Fiume resterà porto franco. Sarebbe folle chiudere lo

sbocco al mare all'Ungheria !!!.

I write of these things with the simplicity of an angel, but without an angelic

detachment. Here are questions into which one does not so much rush as get

reluctantly pushed. Currency and banking are dry distasteful questions, but it

is clear that they are too much in the hands of mystery-mongers; it is as much

the duty of anyone who talks and writes of affairs, it is as much the duty of

every sane adult, to bring his possibly poor and unsuitable wits to bear upon

these things, as it is for him to vote or enlist or pay his taxes. Behind the

simple ostensible spectacle of Italy recovering the unredeemed Italy of the

Trentino and East Venetia, goes on another drama. Has Italy been sinking into

something rather hard to define called “economic slavery”? Is she or is she not

escaping from that magical servitude? Before this question has been under

discussion for a minute comes a name -for a time I was really quite unable to

decide whether it is the name of the villain in the piece or of

the maligned

heroine, or a secret society or a gold mine, or a pestilence or a delusion - the

name of the Banca Commerciale Italiana

**.

Forse sono un pò ingenuo nel trattare simili cose. Dietro l'apparente semplice

spettacolo di un paese che sta cercando di recuperare il Trentino e la

Venetia Giulia, continua un altro dramma. L'Italia è affondata in qualcosa di

piuttosto duro come si definirebbe la "schiavitù economica". E qui purtroppo

bisogna scendere a parlare della Banca Commerciale Italiana, eroina del

maligno, società segreta, miniera d'oro, o pestilenza e inganno.

Banking in a

country undergoing so rapid and vigorous an economic development as

Italy is very different from the banking we simple English know of at home.

Banking in England, like land-owning, has hitherto been a sort of hold up. There

were always borrowers, there were always tenants, and all that had to be done

was to refuse, obstruct, delay and worry the helpless borrower or would-be

tenant until the maximum of security and profit was obtained. I have never

borrowed but I have built, and I know something of the extreme hauteur of

property of England towards a man who wants to do anything with land, and with

money I gather the case is just the same. But in Italy, which already possessed

a sunny prosperity of its own upon mediaeval lines, the banker has had to be

suggestive and persuasive, sympathetic and helpful. These are unaccustomed

attitudes for British capital. The field has been far more attractive to the

German banker, who is less of a proudly impassive usurer and more of a partner,

who demands less than absolute security because he investigates more

industriously and intelligently. This great bank, the Banca Commerciale

Italiana, is a bank of the German type: to begin with, it was certainly

dominated by German directors; it was a bank of stimulation, and its activities

interweave now into the whole fabric of Italian commercial life. But it has

already liberated itself from German influence, and the bulk of its capital is

Italian. Nevertheless I found discussion ranging about firstly what the Banca

Commerciale essentially was, secondly what it might become, thirdly what it

might do, and fourthly what, if anything, had to be done to it.

Le banche in un paese così nuovo e giovane sono cosa diversa dalle nostre. !! ma

in Italia dove opera il banchiere tedesco questo è poco più di un usuraio.

Questa grande banca, la Banca Commerciale Italiana, è una banca di tipo tedesco

creata da tedeschi e diretta da tedeschi. Le sue attività si intessono ora nel

tessuto intero della vita italiana. Oggi si dice che non c'è più il loro

capitale e parimenti l'influenza

(quando Wells scrive l'Italia non ha ancora

dichiarato guerra alla Germania !!! :siamo in agosto del 16 e sono due anni che

si combatte in Europa) tanto che più sotto si precisa

To-night,” said my companion,

“I think we shall declare war upon Germany. The

decision is being made.)Tuttavia ho trovato chi discuteva di cosa fosse in primo luogo la Banca

Commerciale ed in secondo luogo cosa potesse diventare e via cosi.

It is a novelty

to an English mind to find banking thus mixed up with politics,

but it is not a novelty in Italy. All over Venetia there are agricultural banks

which are said to be “clerical.” I grappled with this mystery. “How are they

clerical?” I asked Captain Pirelli. “Do they lend money on bad security to

clerical voters, and on no terms whatever to anti-clericals?” He was quite of my

way of thinking. “Pecunia non olet,” he said; “I have never yet smelt a clerical

fifty lira note.” . . But on the other hand Italy is very close to Germany;

she wants easy money for development, cheap coal, a market for various products.

The case against the Germans - this case in which the Banca Commerciale Italiana

appears, I am convinced unjustly, as a suspect - is that they have turned this

natural and proper interchange with Italy into the acquisition of German power.

That they have not been merely easy traders, but patriotic agents. It is alleged

that they used their early “pull” in Italian banking to favour German

enterprises and German political influence against the development of native

Italian business; that their merchants are not bona-fide individuals, but

members of a nationalist conspiracy to gain economic controls. The German is a

patriotic monomaniac. He is not a man but a limb, the worshipper of a national

effigy, the digit of an insanely proud and greedy Germania, and here are the

natural consequences. It is a novelty

to an English mind to find banking thus mixed up with politics,

but it is not a novelty in Italy. All over Venetia there are agricultural banks

which are said to be “clerical.” I grappled with this mystery. “How are they

clerical?” I asked Captain Pirelli. “Do they lend money on bad security to

clerical voters, and on no terms whatever to anti-clericals?” He was quite of my

way of thinking. “Pecunia non olet,” he said; “I have never yet smelt a clerical

fifty lira note.” . . But on the other hand Italy is very close to Germany;

she wants easy money for development, cheap coal, a market for various products.

The case against the Germans - this case in which the Banca Commerciale Italiana

appears, I am convinced unjustly, as a suspect - is that they have turned this

natural and proper interchange with Italy into the acquisition of German power.

That they have not been merely easy traders, but patriotic agents. It is alleged

that they used their early “pull” in Italian banking to favour German

enterprises and German political influence against the development of native

Italian business; that their merchants are not bona-fide individuals, but

members of a nationalist conspiracy to gain economic controls. The German is a

patriotic monomaniac. He is not a man but a limb, the worshipper of a national

effigy, the digit of an insanely proud and greedy Germania, and here are the

natural consequences.

Per noi trovare una banca che si immischia nella politica è una novità ma non

qui in Italia. Nel Veneto si sono banche agricole che si definiscono clericali

(si riferisce probabilmente alla dizione Banca Cattolica ..... ) così ho chiesto

al capitano Pirelli addetto alle P.R.

(Alberto Pirelli

padre di Leopoldo, in Cavalleria come il fratello Piero)

"come si fa ad essere clericali ? si danno

i soldi solo in cambio dei voti dei cattolici

?"

"Pecunia non olet" mi risponde lui - Il denaro non puzza

- In altri campi c'è

un abisso con la Germania e forse questi sulla Commerciale sono

sospetti infondati. È acclarato però che hanno usato la banca per favorire le imprese tedesche

e l'influenza politica tedesca contro lo sviluppo di affari nazionali italiani. Il

tedesco è un patriota monomaniaco e queste sono le conseguenze.

The case of the individual Italian compactly is this:

“We do not like

the

Austrians and Germans. These Imperialisms look always over the Alps. Whatever

increases German influence here threatens Italian life. The German is a German

first and a human being afterwards. . . . But on the other hand England seems

commercially indifferent to us and France has been economically hostile . . . ”

“After all,” I said presently, after reflection, “in that matter of Pecunia non

olet; there used to be fusses about European loans in China. And one of the

favourite themes of British fiction and drama before the war was the unfortunate

position of the girl who accepted a loan from the wicked man to pay her debts at

bridge.” “Italy,” said Captain Pirelli, “isn’t a girl. And she hasn’t been

playing bridge (gioco).”

I incline on the whole to his point of view. Money is facile cosmopolitan stuff.

I think that any bank that settles down in Italy is going to be slowly and

steadily naturalised Italian, it will become more and more Italian until it is

wholly Italian. I would trust Italy to make and keep the Banca Commerciale

Italiana Italian. I believe the Italian brain is a better brain than the German

article. But still I heard people talking of the implicated organisation as if

it were engaged in the most insidious duplicities. “Wait for only a year or so

after the war,” said one English authority to me, “and the mask will be off and

it will be frankly a ‘Deutsche Bank’ once more.” They assure me that then German

enterprises will be favoured again, Italian and Allied enterprises blockaded and

embarrassed, the good understanding of Italians and English poisoned, entirely

through this organisation. . . .

"Noi non amiamo gli austriaci e i tedeschi, ma i francesi ci sono ostili e gli

Inglesi se ne fregano, cosa avreste fatto voi ? Uno dei temi preferiti della

drammaturgia inglese d'anteguerra era la scomoda posizione di una sfortunata

ragazza che ha accettato un prestito da un uomo malvagio per pagare i suoi

debiti di gioco". "L'Italia," ha detto il capitano Pirelli "non è

una ragazza. E

non sta giocando a Bridge". Io credo che i cervelli italiani

in questo campo (bancario)

siano migliori di tanti altri. ... "Aspettate anche solo un anno più o meno dopo

la guerra," mi ha detto un'autorità inglese , "e la maschera volerà via e sarà

di nuovo una "deutsche bank". Mi assicurano che le imprese tedesche poi saranno

favorite di nuovo, quelle italiane ed Alleate boicottate.

The reasonable uncommercial man would like to reject all this last sort of talk

as “suspicion mania.” So far as the Banca Commerciale Italiana goes, I at least

find that easy enough; I quote that instance simply because it is a case where

suspicion has been dispelled, but in regard to a score of other business veins

it is not so easy to dispel suspicion.

This war has

been a shock to reasonable

men the whole world over. They have been forced to realise that after all a

great number of Germans have been engaged in a crack-brained conspiracy against

the non-German world; that in a great number of cases when one does business

with a German the business does not end with the individual German. We hated to

believe that a business could be tainted by German partners or German

associations. If now we err on the side of over-suspicion, it is the German’s

little weakness for patriotic disingenuousness that is most to blame. . .

Questa guerra è uno shock per le persone ragionevoli di tutto il mondo. Tutti

hanno realizzato che i tedeschi hanno ingaggiato una guerra contro i non

tedeschi e che in molti casi quando si fanno affari con questi , l'affare non

termina con chi hai di fronte.

But anyhow I do not think there is much good in a kind of witch-smelling among

Italian enterprises to find the hidden German. Certain things are necessary for

Italian prosperity and Italy must get them.

The Italians

want intelligent and

helpful capital. They want a helpful France. They want bituminous coal for

metallurgical purposes. They want cheap shipping. The French too want

metallurgical coal. It is more important for civilisation, for the general

goodwill of the Allies and for Great Britain that these needs should be supplied

than that individual British money-owners or ship-owners should remain

sluggishly rich by insisting upon high security or high freights. The control of

British coal-mining and shipping is in the national interests—for international

interests—rather than for the creation of that particularly passive, obstructive,

and wasteful type of wealth, the wealth of the mere profiteer, is as urgent a

necessity for the commercial welfare of France and Italy and the endurance of

the Great Alliance as it is for the well-being of the common man in Britain.

Gli italiani vogliono capitali "puliti" da Francia. Gli serve carbone

bituminoso (il più sporco), noli a buon mercato. Il controllo statale del carbone è negli

interessi nazionali, piuttosto che la nascita di un approfittatore puro

semplice, è una urgente necessità questa per il benessere commerciale di Francia

ed Italia e la perseveranza della Grand'Alleanza come è per il benessere

dell'uomo comune in Gran Bretagna.

I left my military

guide at Verona on Saturday afternoon and reached Milan in

time to dine outside Salvini’s in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, with an

Italian fellow story-writer. The place was as full as ever; we had to wait for a

table. It is notable that there were still great numbers of young men not in

uniform in Milan and Turin and Vicenza and Verona; there was no effect anywhere

of a depletion of men. The whole crowded place was smouldering with excitement.

The diners looked about them as they talked, some talked loudly and seemed to be

expressing sentiments. Newspaper vendors appeared at the intersection of the

arcades, uttering ambiguous cries, and did a brisk business of flitting white

sheets among the little tables.

“To-night”

said my companion“I think we shall declare war upon Germany. The

decision is being made”

I asked intelligently why this had not been done before. I forget the precise

explanation he gave. A young soldier in uniform, who had been dining at an

adjacent table and whom I had not recognised before as a writer I had met some

years previously in London, suddenly joined in our conversation, with a slightly

different explanation. I had been carrying on a conversation in slightly

ungainly French, but now I relapsed into English.

Lascio la mia guida sabato pomeriggio e raggiungo Milano in tempo per

pranzare al Salvini in Galleria con un amico italiano scrittore. Il locale è

pieno e dobbiamo anche aspettare per un tavolo. E' sorprendente vedere

tanti giovani non in divisa. Stanotte, dice il mio accompagnatore, è certo che

si dichiari guerra alla Germania. Gli chiedo perchè non l'avete fatto

prima ma non ricordo la risposta. Un giovane in uniforme che pranza al tavolo a

fianco, e che subito non riconosco come lo scrittore che vidi a Londra, entra

nella nostra discussione con un'altra spiegazione.

But indeed the matter of that declaration of war is as plain as daylight; the

Italian national consciousness has not at first that direct sense of the German

danger that exists in the minds of the three northern Allies.

To the Italian

the traditional enemy is Austria, and this war is not primarily a war for any other

end than the emancipation of Italy. Moreover we have to remember that for years

there has been serious commercial friction between France and Italy, and

considerable mutual elbowing in North Africa. Both Frenchmen and Italians are

resolute to remedy this now, but the restoration of really friendly and trustful

relations is not to be done in a day. It has been an extraordinary misfortune

for Great Britain that instead of boldly taking over her shipping from its

private owners and using it all, regardless of their profit, in the interests of

herself and her allies, her government has permitted so much of it as military

and naval needs have not requisitioned to continue to ply for gain, which the

government itself has shared by a tax on war profits. The Anglophobe elements in

Italian public life have made the utmost of this folly or laxity in relation

more particularly to the consequent dearness of coal in Italy. They have carried

on an amazingly effective campaign in which this British slackness with the

individual profiteer, is represented as if it were the deliberate greed of the

British state. This certainly contributed very much to fortify Italy’s

disinclination to slam the door on the German connection.

Per gli italiani il tradizionale nemico è l'Austria e lo scopo primario è

emanciparsi dalla sua custodia. Non si possono dimenticare le frizioni

commerciali fra Francia e Italia, anche per il N. Africa.

Sembra che abbiano compreso tutto ciò ma non si risolvono in un giorno queste

cose, se ci mettiamo anche quanto successo sui noli britannici (vedi in calce).

I did my best to

make it clear to my two friends that so far from England

exploiting Italy, I myself suffered in exactly the same way as any Italian,

through the extraordinary liberties of our shipping interest. “I pay as well as

you do,” I said; “the shippers’ blockade of Great Britain is more effective than

the submarines’. My food, my coal, my petrol are all restricted in the sacred

name of private property. You see, capital in England has hitherto been not an

exploitation but a hold-up. We are learning differently now. . . . And anyhow,

Mr. Runciman has been here and given Italy assurances. . . . ”

In the train to Modane this old story recurred again. It is imperative that

English readers should understand clearly how thoroughly these little matters

have been worked by the enemy. Some slight civilities led to a conversation that

revealed the Italian lady in the corner as an Irishwoman married to an Italian,

and also brought out the latent English of a very charming elderly lady opposite

to her. She had heard a speech, a wonderful speech from a railway train, by “the

Lord Runciman.” He had said the most beautiful things about Italy.

I did my best to echo these beautiful things.

Ho fatto del mio meglio per spiegare ai due amici, che soffro al pari di loro.

Il blocco dei trasportatori e più grande di quello sottomarino. Il mio cibo, il mio carbone, la mia benzina sono razionati nel nome sacro della

proprietà privata. Sul treno per Modane questa vecchia storia è ricorsa di nuovo. È

imperativo che il lettore Inglese sappia queste cose a fondo, queste piccole

questioni che hanno lavorato per il nemico.

Then the Irishwoman remarked that Mr. Runciman had not satisfied everybody. She

and her husband had met a minister

-I found afterwards he was one of the members

of the late Giolitti government—who had been talking very loudly and scornfully

of the bargain Italy was making with England. I assured her that the desire of

England was simply to give Italy all that she needed.

“But,” said the husband casually, “Mr. Runciman is a shipowner.” -I found afterwards he was one of the members

of the late Giolitti government—who had been talking very loudly and scornfully

of the bargain Italy was making with England. I assured her that the desire of

England was simply to give Italy all that she needed.

“But,” said the husband casually, “Mr. Runciman is a shipowner.”

I explained that he was nothing of the sort. It was true that he came of a

shipowning family—and perhaps inherited a slight tendency to see things from a

shipowning point of view—but in England we did not suspect a man on such a score

as that.

“In Italy I think we should,” said the husband of the Irish lady.

Poi l'irlandese ha osservato che il Sig. Runciman non aveva soddisfatto tutti.

Lei e suo marito ha incontrato un ministro-ho trovato in seguito è stato uno dei

membri della fine del governo Giolitti, che era stata molto forte e parlare

scornfully del patto che l'Italia è stata con l'Inghilterra. Mi ha assicurato

che il suo desiderio d'Inghilterra è stato semplicemente quello di dare tutto

ciò che l'Italia aveva bisogno. "Ma", ha detto il marito casualmente, "Mr.

Runciman è un armatore. "

Ho spiegato che era niente del genere. Si è vero che è venuto di una famiglia di

armatori e forse ereditato una leggera tendenza a vedere le cose da un punto di

vista armatori, ma in Inghilterra non abbiamo il sospetto di un uomo su un

cliente che come. "In Italia credo che dovremmo", ha detto il marito della

signora irlandese.

This incidental discussion

is a necessary part of my impression of Italy at war.

The two western allies and Great Britain in particular have to remember Italy’s

economic needs, and to prepare to rescue them from the blind exploitation of

private profit. They have to remember these needs too, because, if they are left

out of the picture, then it becomes impossible to understand the full measure of

the risk Italy has faced in undertaking this war for an idea. With a Latin

lucidity she has counted every risk, and with a Latin idealism she has taken her

place by the side of those who fight for a liberal civilisation against a

Byzantine imperialism.

As I came out of the brightly lit Galleria Vittorio Emanuele into the darkened

Piazza del Duomo I stopped under the arcade and stood looking up at the shadowy

darkness of that great pinnacled barn, that marble bride-cake, which is, I

suppose, the last southward fortress of the Franco-English Gothic.

“It was here,” said my host, “that we burnt the German stuff.” “What German

stuff?” “Pianos and all sorts of things. From the shops. It is possible, you

know, to buy things too cheaply—and to give too much for the cheapness.”

Questa discussione fortuita è una parte necessaria delle mie impressioni sul

Vostro paese in guerra. I due alleati occidentali e la Gran Bretagna in

particolare devono ricordare i bisogni economici Italiani ed evitare che cadano

in mano al cieco profitto privato. Devono ricordare questi bisogni anche perché

se si lasciano fuori poi diventa impossibile capire la misura del rischio

affrontato nell'impresa di questa guerra dall'Italia intera per un'idea. Con una

lucidità latina ha contato ogni rischio, e con un idealismo latino ha portato il

suo contributo per una civilizzazione liberale contro un imperialismo bizantino.

Come sono uscito dalla luminosa Galleria Vittorio Emanuele e mi sono gettato

nella buia piazza Duomo ho volto lo sguardo a quel capolavoro d'arte gotica

Franco Inglese ultima fortezza a sud .

""E 'stato qui", disse il mio ospite ", che abbiamo bruciato

la roba? tedesca".

"Che roba?" "Pianoforti e ogni genere di cose.

**

In altra parte del sito ho riassunto così la vicenda Commerciale su cui s'era

fatto e si faceva anche molto Gossip -

Capita, quando si incontrano vicende di spionaggio, di sobbalzare sulla sedia

alla lettura di certi nomi. Ma questo è un campo dove i "si dice" si sprecano.

E’ successo così anche quando è uscito il nome della Banca Commerciale Italiana,

banca famosa per essere nata da imprenditori svizzeri e tedeschi nel 1894 (salvo

per 100.000 lire sottoscritte dal Conte Alfonso Sanseverino-Vimercati nominato

Primo Presidente) e che di tedesco si trascinò per anni oneri e onori. La

Commerciale era il nido, la balia, la levatrice di tutte le principali grandi

aziende italiane nate all’inizio del 900 che prima o poi tornavano allo

sportello per curarsi le ferite o trovare acquirenti. Quando scoppiò la grande

guerra il sospetto che a manovrare le aziende militarizzate italiane fossero i

tedeschi (e ne vedremo anche i motivi) era altissimo se circolavano simili

rapporti….Fascicolo: Banca Commerciale ed Affini 11/9/1915 - Fondo: Carte di A.

Salandra Biblioteca Comunale Ruggero Bonghi di Lucera - Oggetto: Informazioni

sulla Commerciale, sulla Ansaldo (Perrone), sul giornalista Naldi e su Garroni,

ambasciatore dell'Italia in Turchia

- "E' attorno alla Banca Commerciale che stanno tuttora raggruppati

saldamente in Italia gli interessi germanici: e questi solo dal ritorno del

giolittismo possono sperare la loro salvezza. Unico gruppo finanziario

autorevolmente opposto a quello della Commerciale è quello che fa capo alla

ditta Ansaldo. In questi giorni si sta cercando di attirare pure questo

nell'orbita della Banca Commerciale. Gira voce di una conferenza di Giolitti con

il comm. Pio Perrone, dell'Ansaldo, incontro che non sembra esserci ancora

stato, mentre si è svolto invece l'incontro tra Perrone e Fenoglio per tentare

un accordo tra i due gruppi. Inoltre il Consorzio per l'impianto di una fabbrica

di munizioni a Genova, sotto la presidenza della Camera di Commercio, sicuro

presidio della Banca Commerciale, è in sostanza un abile tentativo per

raggruppare su un terreno neutro sotto l'egida della commerciale, il gruppo

Terni, col gruppo Ansaldo e le società di navigazione, la presidenza dell'Odero,

la vicepresidenza al Perrone, ottimo mezzo di avvicinamento dei due elementi che

si vogliono fondere. Tale sforzo della Commerciale nasce forse da

un'esagerazione della campagna antitedesca in Italia svolta dai Perrone. Questa

trae, invece, le sue forze da una ben più intima e profonda convinzione del

danno che il nostro vassallaggio verso la Germania arreca alla nostra economia

nazionale". - "E' attorno alla Banca Commerciale che stanno tuttora raggruppati

saldamente in Italia gli interessi germanici: e questi solo dal ritorno del

giolittismo possono sperare la loro salvezza. Unico gruppo finanziario

autorevolmente opposto a quello della Commerciale è quello che fa capo alla

ditta Ansaldo. In questi giorni si sta cercando di attirare pure questo

nell'orbita della Banca Commerciale. Gira voce di una conferenza di Giolitti con

il comm. Pio Perrone, dell'Ansaldo, incontro che non sembra esserci ancora

stato, mentre si è svolto invece l'incontro tra Perrone e Fenoglio per tentare

un accordo tra i due gruppi. Inoltre il Consorzio per l'impianto di una fabbrica

di munizioni a Genova, sotto la presidenza della Camera di Commercio, sicuro

presidio della Banca Commerciale, è in sostanza un abile tentativo per

raggruppare su un terreno neutro sotto l'egida della commerciale, il gruppo

Terni, col gruppo Ansaldo e le società di navigazione, la presidenza dell'Odero,

la vicepresidenza al Perrone, ottimo mezzo di avvicinamento dei due elementi che

si vogliono fondere. Tale sforzo della Commerciale nasce forse da

un'esagerazione della campagna antitedesca in Italia svolta dai Perrone. Questa

trae, invece, le sue forze da una ben più intima e profonda convinzione del

danno che il nostro vassallaggio verso la Germania arreca alla nostra economia

nazionale".

E l’anno dopo ci pensava (Don) Giovanni Preziosi, interventista, antisemita poi

fascista con l’opera -

La Germania alla conquista dell’Italia -: con nota del

Prof. Maffeo Pantaleoni – Indice: «Il pangermanesimo: metodi e pericoli - Le

finalità della penetrazione germanica in Italia - Il cavallo di Troia (Per

rendere l’Italia strumento della politica tedesca); Origini e scopi della Banca

Commerciale Italiana; Le dimissioni dei Consiglieri esteri della Banca

Commerciale; La retata delle società anonime; Per favorire l’industria e il

commercio tedesco; Le informazioni riservate; Per la conquista delle industrie

italiane; La conquista della marina mercantile; Le industrie siderurgiche e

d’armamenti nelle mani della banca tedesca; La conquista delle industrie

elettriche; Nelle elezioni politiche; L’assorbimento del nostro risparmio; Lo

sfruttamento dell’emigrazione; I tedeschi domandavano la cittadinanza italiana

alla vigilia della guerra; (E la stampa?) - Giolitti e la Banca Commerciale - Un

comunicato in difesa della banca tedesca nella stampa inglese - La penetrazione

germanica in Inghilterra e il “metodo della catena”.

Ce n’era abbastanza da far saltare le coronarie a

chiunque (ma il direttore della Commerciale era Ebreo): ma in altre sedi poi lo

si taccia durante il fascismo di fare comunella con la Banca per fare le scarpe

al duce dal suo Ufficio del quotidiano “Il mezzogiorno”. Firmerà il manifesto

della razza e il 25 aprile 1945 si getterà dalla finestra con la moglie

ufficiale (da spretato).

Tutto questo chiacchiericcio nasceva anche dalla figura dei primi amministratori

delegati OTTO JOEL etichettato come Ebreo oltre che massone e FEDERICO WEILL

A.D. dal 1908 al 1914 (dimissioni obbligate) e da Giuseppe Toeplitz con la

stessa carica dal ’17: Toeplitz nasce a Varsavia nel 1866, da famiglia della

borghesia ebraica ma frequenta la facoltà di ingegneria dell'università di

Aquisgrana. Nel 1891 viene in Italia chiamatovi da Otto Joel, suo lontano

cugino. Prima dell'assunzione alla Banca Commerciale (1895) lavora alle filiali

di Genova della Banca Generale e della Banca Russa per il Commercio Estero. E'

direttore della sede di Napoli della Commerciale (1898) e di quella di Venezia

(1900) poi condirettore e direttore della sede centrale di Milano nel 1906. Nel

1912 acquista la cittadinanza italiana e prima sembra lasci anche la fede

giudaica.. Alla sede centrale trova anche FEDERICO WEILL, altro tedesco

trapiantato in Italia, già direttore della filiale palermitana del Credito

Mobiliare. Nel 1914, alla vigilia della grande guerra, le posizioni neutraliste

di Toeplitz vengono attaccate dall’interventismo nazionalista: è la nascita

della banca degli spioni.

Mancava solo il prestito obbligazionario Fiat non collocato (siamo alla vigilia

di una guerra e per gli industriali son sempre soldi che corrono) per

qualificare la Banca come Giolittiana, l’uomo della neutralità. A dir il vero

anche la Fiat si dichiarava neutralista in vista delle commesse della Marina

Tedesca. Quando Toeplitz acquista dall’ex consigliere della tedesca Mannesmann,

Eugen Hannesen, la villa di Sant'Ambrogio Olona sul lago di Varese venne

tacciato di scambiare messaggi ottici dalla torretta osservatorio con agenti

tedeschi nella vicina svizzera (Monte Generoso).

Per concludere e non dilungare oltre di una chiacchiera che lascia il tempo che

trova riporto il titolo di un recente articolo apparso sul Corriere della Sera

del

04/03/2003 - Comit (Banca Commerciale Italiana), conto aperto al signor Mussolini: Dagli archivi della banca

le prove dei finanziamenti di Toeplitz al duce e al «Il Popolo d’Italia» !!! I

finanziamenti al Popolo d’Italia da parte della Comit aumentano quando il

fascismo è al potere. «Un primo finanziamento sicuro - scrive Giorgio Fabre

- risale al

26 gennaio 1924, altro periodo di crisi del giornale, ed era di 500 mila lire.

Una seconda tranche fu versata il 9 gennaio 1925 (250 mila lire); un’altra

ancora il 27 ottobre 1925 (250 mila lire); infine il 22 febbraio 1928 altre 500

mila lire. Siamo già su tutt’altra sponda. Fonte- Quaderni di

storia. Il figlio di Fabre Lodovico asserisce poi che il padre finanziò anche D’Annunzio

che per la verità lo cercò come Ministro delle Finanze ripiegando poi su Maffeo Pantaleoni che stava da tutt’altra parte !?.

come direbbe Preziosi.

|

The Mountain War 1a parte traduzione

http://www.frontedolomitico.it/Testimonianze/FronteDolomiticoWells.htm

altre sue opere oltre quelle in immagine

The Wheels of Chance (1896)

The History of Mr Polly (1910)

Bealby: A Holiday (1915)

Love and Mr Lewisham (1900)

The First Men in the Moon (1901)

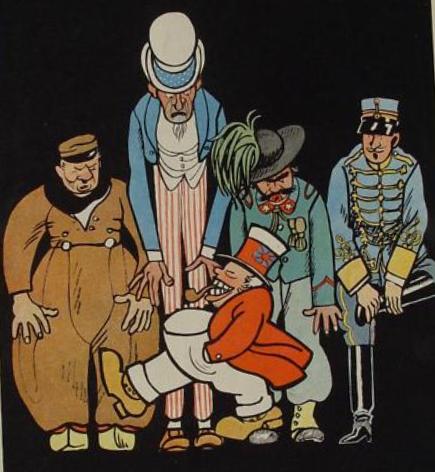

The “Prize-Taker” (From Lustige Blaetter, Berlin)

"How long will you allow this brute to

tread on your corns?"

[The allusion is to England's

attitude toward neutral shipping]

Il Pirata - "Per quanto tempo consentirai che questo bruto cammini sui

tuoi calli"? [l'allusione è all'atteggiamento dell'Inghilterra verso

i noli dei paesi neutrali]. Da sinistra l'olandese,

l'americano, l'italiano e xxxx naturalmente ante 1915 |

|

Torna

all'indice delle curiosità

|