Introduction to Turkey

The Country

General Outline

The lands of Turkey are

located at a point where the three continents making up the old world. Asia,

Africa and Europe are closest to each other, and straddle the point where

Europe and Asia meet. Geographically, the country is located in the northern

half of the hemisphere at a point that is about halfway between the equator

and the north pole, at a longitude of 36 degrees N to 42 degrees N and a

latitude of 26 degrees E to 45 degrees E. Turkey is roughly rectangular in

shape and is 1,660 kilometers wide.

Because of its geographical

location the mainland of Anatolia has always found favour throughout history,

and is the birthplace of many great civilizations. It has also been prominent

as a centre of commerce because of its land connections to three continents

and the sea surrounding it on three sides.

Area

The actual area of Turkey

inclusive of its lakes, is 814,578 square kilometres, of which 790,200 are in

Asia and 24,378 are located in Europe.

Boundaries

The land borders of Turkey

are 2,573 kilometres in total, and coastlines (including islands) are another

8,333 kilometres, Turkey has two European and six Asian countries for

neighbours along its land borders.

The land border to the

northeast with the commonwealth of Independent States is 610 kilometres long;

that with Iran, 454 kilometres long, and that with Iraq 331 kilometres long.

In the south is the 877 kilometre-long border with Syria, which took its

present form in 1939, when the Republic of Hatay joined Turkey. Turkey's

borders on the European continent consist of a 212-kilometre frontier with

Greece and a 269-kilometre border with Bulgaria.

Turkey is generally divided

into seven regions: the Black Sea region, the Marmara region, the Aegean, the

Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, the East and Southeast Anatolia regions. The

uneven north Anatolian terrain running along the Black Sea resembles a narrow

but long belt. The land of this region is approximately 1/6 of Turkey's total

land area.

The Marmara region

covers the area encircling the Sea of Marmara, includes the entire European

part of Turkey, as well as the northwest of the Anatolian plain. Whilst the

region is the smallest of the regions of Turkey after the Southeast Anatolia

region, it has the highest population density of all the regions.

The most important peak in

the region is Uludag (2,543 metres), at the same time it is a major winter

sports and tourist centre. In the Anatolian part of the region there are

fertile plains running from east to west.

The Aegean region

extends from the Aegean coast to the inner parts of western Anatolia. There

are significant differences between the coastal areas and those inland, in

terms of both geographical features and economic and social aspects.

In general, the mountains in

the region fall perpendicularly into the sea. and the plains run from east to

west. The plains through which Gediz, Kücük Menderes and Bakircay rivers

flow carry the same names as these rivers.

In the Mediterranean

region, located in the south of Turkey, the western and central Taurus

Mountains suddenly rise up behind the coastline. The Amanos mountain range is

also in the area.

The Central Anatolian

region is exactly in the middle of Turkey and gives the appearance of

being less mountainous compared with the other regions. The main peaks of the

region are Karadag, Karacadag, Hasandag and Erciyes (3.917 metres).

The Eastern Anatolia

region is Turkey's largest and highest region. About three fourths of it

is at an altitude of 1,500-2,000 metres. Eastern Anatolia is composed of

individual mountains as well as of whole mountain ranges, with vast plateaus

and plains. The mountains: There are numerous inactive volcanoes in the

region, including Nemrut, Suphan, Tendurek and Turkey's highest peak, Mount

Agri (Ararat), which is 5,165 metres high.

At the same time, several

plains extended along the course of the River Murat, a tributary of the Firat

(Euphrates). These are the plains of Malazgirt, Mus, Capakcur, Uluova and

Malatya.

The Southeast Anatolia

region is notable for the uniformity of its landscape, although the

eastern part of the region is comparatively more uneven than its western

areas.

Coastlines

Turkey is surrounded by sea

on three sides, by the Black Sea in the north, the Mediterranean in the south

and the Aegean Sea in the west. In the northwest there is also an important

internal sea, the Sea of Marmara, between the straits of the Dardanelles and

the Bosphorus, important waterways that connect the Black Sea with the rest of

the world.

Because the mountains in the

Black Sea region run parallel to the coastline, the coasts are fairly smooth,

without too many indentations or projections. The length of the Black Sea

coastline in Turkey is 1,595 kilometres, and the salinity of the sea is 17%.

The Mediterranean coastline runs for 1,577 kilometres and here too the

mountain ranges are parallel to the coastline.

The salinity level of the

Mediterranean is about double that of the Black Sea.

Although the Aegean coastline

is a continuation of the Mediterranean coast, it is quite irregular because

the mountains in the area fall perpendicularly into the Aegean Sea. As a

result, the length of the Aegean Sea coast is over 2,800 kilometres. The

coastline faces out to many islands.

The Marmara Sea is located

totally within national boundaries and occupies an area of 11,350 square

kilometres. The coastline of the Marmara Sea is over 1,000 kilometres long; it

is connected to the Black Sea by the Bosphorus and with the Mediterranean by

the Dardanelles.

Rivers

Most of the rivers of Turkey

flow into the seas surrounding the country. The Firat (Euphrates) and Dicle

(Tigris) join together in Iraq and flow into the Persian Gulf. Turkey's

longest rivers, the Kizilirmak, Yesilirmak and Sakarya, flow into the Black

Sea. The Susurluk, Biga and Gonen pour into the Sea of Marmara, the Gediz,

Kucuk Menderes, Buyuk Menderes and Meric into the Aegean, and the Seyhan,

Ceyhan and Goksu into the Mediterranean .

Lakes

In terms of numbers of lakes,

the Eastern Anatolian region is the richest. It contains Turkey's largest,

Lake Van (3.713 square kilometres), and the lakes of Ercek, Cildir and Hazar.

There are also many lakes in the Taurus mountains area: the Beysehir and

Egirdir lakes, and the lakes that contain bitter waters like the Burdur and

Acigoller lakes, for example. Around the Sea of Marmara are located the lakes

of Sapanca, Iznik, Ulubat, Manyas, Terkos, Kucukcekmece and Buyukcekmece. In

Central Anatoia is the second largest lake in Turkey: Tuzgolu: The waters of

this lake are shallow and very salty. The lakes of Aksehir and Eber are also

located in this region.

As a result of the

construction of dams during the past thirty years, several large dam lakes

have come into existence. Together with the Ataturk Dam lake which started to

collect water in January 1990, the following are good examples: Keban,

Karakaya, Altinkaya, Adiguzel, Kilickaya, Karacaoren, Menzelet, Kapulukaya,

Hirfanli, Sariyar and Demirkopru.

The Climate

Although Turkey is situated

in a geographical location where climatic conditions are quite temperate, the

diverse nature of the landscape , and the existence in particular of the

mountains that run parallel to the coasts, results in significant differences

in climatic conditions from one region to the other. While the coastal areas

enjoy milder climates, the inland Anatolian plateau experiences extremes of

hot summers and cold winters with limited rainfall.

A New World For The Turks : Anatolia

Anatolia

has given rise to many civilizations in the course of history. Although not as

advanced as Egypt or Mesopotamia, the Hatti, who spoke a language

characterized by prefixes,were nevertheless one of the more advanced societies

of their age(3000-2000B.C.). The objects on display at the Ankara Museum of

Anatolian Civilizations constitute the finest Bronze Age collection in the

world next to the Ur Treasure in the British Museum. The Ankara collection,

dated at 2000-1900B.C., comes from tumuli at Alacahoyuk, Horoztepe and

Mahmatlar, and includes artifacts in gold silver, electrum bronze and ceramic. Anatolia

has given rise to many civilizations in the course of history. Although not as

advanced as Egypt or Mesopotamia, the Hatti, who spoke a language

characterized by prefixes,were nevertheless one of the more advanced societies

of their age(3000-2000B.C.). The objects on display at the Ankara Museum of

Anatolian Civilizations constitute the finest Bronze Age collection in the

world next to the Ur Treasure in the British Museum. The Ankara collection,

dated at 2000-1900B.C., comes from tumuli at Alacahoyuk, Horoztepe and

Mahmatlar, and includes artifacts in gold silver, electrum bronze and ceramic.

An Outpost Against Invasion From The Balkans

: Troy

During

the time of the Hatti, Troy I (3000-2500) and Troy II (2500-2200) represented

the Bronze Age in northwestern Anatolia, that is to say at Canakkale.Both fell

within the sphere of Aegean culture, and Troy II had a particularly brilliant

age. The gold vessels unearthed by Heinrich Schliemann, and kept in the Berlin

Völkerkunde Museum, unfortunately vanished during World War II. The riches of

Troy are now represented by the gold jewellery on display in the Istanbul

museum of Archaelogy. Troy III-V (2200-1800B.C.) is a continuation of Troy II. During

the time of the Hatti, Troy I (3000-2500) and Troy II (2500-2200) represented

the Bronze Age in northwestern Anatolia, that is to say at Canakkale.Both fell

within the sphere of Aegean culture, and Troy II had a particularly brilliant

age. The gold vessels unearthed by Heinrich Schliemann, and kept in the Berlin

Völkerkunde Museum, unfortunately vanished during World War II. The riches of

Troy are now represented by the gold jewellery on display in the Istanbul

museum of Archaelogy. Troy III-V (2200-1800B.C.) is a continuation of Troy II.

Migration Of Indo-European Peoples Into

Anatolia

The Hatti-Hittite Princedoms

The Indo-European migrations, which took

place over a vast territory extending from Western Europe to India, brought

some peoples over the Caucasus into Anatolia. The Nesi people settled in

Central Anatolia, the Pala in Paphlygonia, and the Luwians in Southern

Anatolia. In the course of these migrations the new arrivals gradually

captured the Hatti princedoms to form first the Old Hittite Kingdom (1660-1460

B.C.), and than the Great Hittite Kingdom(1460-1190 B.C.).

The Hittite Empire (1660-1190 B.C.)

The

Hittites founded a federative feudal state, and during their final two

centuries constituted one of the two superpowers of the age, the other being

Egypt. Indo-European in origin, the Hittites recognized equality between men

and women,and indeed their law incoporated rights even for slaves. No other

legal system in the world at that time was so advanced. Although the monarchy

passed from father to son, this was a kingship based on the idea of

"primus inter pares",first among equals, for the ruler was required

to bring many matters before the senate, which was made up of aristocrats

known as the Pankus class. The

Hittites founded a federative feudal state, and during their final two

centuries constituted one of the two superpowers of the age, the other being

Egypt. Indo-European in origin, the Hittites recognized equality between men

and women,and indeed their law incoporated rights even for slaves. No other

legal system in the world at that time was so advanced. Although the monarchy

passed from father to son, this was a kingship based on the idea of

"primus inter pares",first among equals, for the ruler was required

to bring many matters before the senate, which was made up of aristocrats

known as the Pankus class.

At

a time in the Near East when the flaying and impaling of enemies was the rule,

when heads and hands would be lopped off and pyramids made of them, the

Hittites were astonishingly humane, almost like civilized of nations today. At

a time in the Near East when the flaying and impaling of enemies was the rule,

when heads and hands would be lopped off and pyramids made of them, the

Hittites were astonishingly humane, almost like civilized of nations today.

The

Hittites adopted the Hatti religion, mythology, language and customs, as well

as their names for places, mountains, rivers and persons. Because the

Mesopotamians called Anatolia "the Land of the Hatti", the newcomers

were mistakenly given the name "Hittite". The

Hittites adopted the Hatti religion, mythology, language and customs, as well

as their names for places, mountains, rivers and persons. Because the

Mesopotamians called Anatolia "the Land of the Hatti", the newcomers

were mistakenly given the name "Hittite".

Hittite architecture was highly original, and

included the strongest city walls of the Near East in the second millenium

B.C. They also built the most magnificent temples, and developed a figurative

art that was to be widespread in Anatolia.

The Ilium of Homer's Iliad

Troy VI (1800-1275 B.C.)

As the Hittites were settling in Central

Anatolia, another Indo-European people were flourishing in the Canakkale

region at Troy VI, which today is one of Turkey's finest ruins, with a city

wall preserved to a height of four meters, and a number of well preserved

megaron type houses.

The Ilium of King Priam, in Homer's epic,

corresponds to layer VIh(1325-1275 B.C.), and was destroyed in an earthquake,

while the city captured by the Achaeans was Troy VIIe (1275-1240/1200 B.C.).

When Troy VIh was destroyed in an earthquake in 1275 B.C., followed by the

pillaging of Troy VIIa in 1240/1200 at the hands of The Achaeans, a staunch

outpost against incursions from the nortwest- an outpost which had stood for

two thousand years was gone. And indeed, the crude hand-made pottery

discovered in Troy VIIb2 / 1240-1190 B.C.),like the Buckelceramic pots found

in Troy VIIb2 (1190-110), are of Balkan Origin. Having captured Troy in 1200,

the Balkan peoples proceeded to occupy Anatolia in waves; around 1190 they

destroyed the Hittite capital of Hattusas and penetrated as far south as the

Assyrian border.

Civilizations Which Influenced The Hellens

The Urartu Kingdom(860-580 B.C.) and The

Phrygians(750-300 B.C.)

In southeastern and eastern Anatolia, which

seem not to have been much affected by the migrations of the Balkan peoples,

the Late Hittite Princedoms(1200-700 B.C.) and the Urartu Kingdom (860-580

B.C.)produced a high level of culture.

In the 8th century B.C. the Hellenes came in

contact with the rich two-thousand-year-old heritage of Mesopotamia through

the intermediary of the Late Hittite Princedoms living in southeastern

Anatolia. The Hellenes acquired the Phoenician alphabet from Al Mina, and the

mythology and figurative art which we see in Homer and Hesiod, from such Late

Hittite cities as Kargamish and Malatya. The helmet of a Hellene in the 8th

century, along with his shield, various belts and different hair styles, were

just like Those of the Hittites. Hellenic figurative and decorative art in the

8th and 7th centuries followed Hittite styles and iconography.

Although

the Urartus were strongly influenced in their art by Assyrian and Late Hittite

example, they produced fine artifacts which they were able to export to Hellas

and Etruscan cities. Although

the Urartus were strongly influenced in their art by Assyrian and Late Hittite

example, they produced fine artifacts which they were able to export to Hellas

and Etruscan cities.

The Phrygians were among the Balkan peoples

who came into Anatolia around the year 1200 B.C., but they first appear on the

scene as a political entitiyafter the year 750 B.C. The Hellenic world knew of

the Phrygian King Midas as a legendary figure with long ears who turned to

gold everything that the touched. The Assyrians, on the other hand , record

that he qas king in 717, 715, 712 and 709 B.C. Although the powerful kingdom

which Midas founded was swept away by the Cimmerians in the First quarter of

the 7th century, scattered groupings of the Phrygians continued to evolve

their civilization in Central Anatolia though the 6th century B.C. The

Phrygian rock temples and treasures in the vicinity of Eskisehir and Afyon are

quite well preserved, and among the finest works produced by their age.

Three Intriguing Anatolian Peoples:

Lydia, Caria and Lycia

The Lydians and Lycians spoke languages that

were fundamentally Indo-European, but both languages had acquired

non-Indo-European elements prior to the Hittite and Hellenic periods. Both

alphabets closely resembled that of the Hellenes. During the reign of Creosus,

fabled for his wealth (575-545 B.C.) the Lydian capital of Sardes was one of

the most brilliant cities of the ancient world.

Although the Carian alphabet resembles the

Lycian, the Carian language has not been deciphered to date. Herodotus says

that according to a cretan legend the Carians were called Leleges and lived on

the islands during the time of the Minoan Kingdom, that is, in the mid-2nd

millenium B.C. The Carians themselves, however, claimed to be native

Anatolians, related to the Lydians and Mysians.

The archaelogical finds pertaining to all

three cultures show strong Hellenic influence. Of the three, the Lycians best

kept their own character. Their monuments hollowed out of the rock are among

the most interesting works of art in ancient Anatolia.

The Ionian Civilization (1050-1030 B.C.)

Following the destruction of Troy, the

Hellenes established cities all along the Western Anatolian shore. In the 9th

century B.C. they produced the first masterpiece of Western Civilization, the

Iliad of Homer.

During the era of the natural philosophers,

i.e. 600-545 B.C., Anatolian culture was of a brilliance unmatched in the

world of its time, superceding Egypt and Mesopotamia Rejecting the idea of

djinns, fairies and mythological causes, the natural philosophers investigated

natural phenomena in a free spirit; Thales, son of the Carian Hexamyes, using

the same methods we would today, predicted an eclipse of the sun for May 28,

585 B.C. This was the first prediction of a natural event in history.

During the occupation of the Persians

(545-333 B.C.), Anatolia relinguished its leadership, but regained it in the

Throughout these centuries, Milletus, Priene,

Ephesus and Teos were among the finest cities in the world, and the Anatolian

architecture of this era greatly influenced Rome.

Bluffer's Guide to the Anatolian Iron

Age By Roger Norman- Turkish Daily News

The Roman Age (30 B.C. - 595 A.D.)

The Romans developed the technique of

mortaring bricks together, thereby producing arches, vaults and domes of large

volume. These were the first major feats of enineering in history, and

although the very first were at Rome, it soon became the turn of Anatolia Fine

cities sprang up not only in the south and west of the peninsula, but also in

its heartland. In all of these cities there were such monumental works as an

agora, gymnasium, stadium, theater, baths and foundations, and many of them

were of marble. The roads, too, were paved with marble and lined with

colonnades, thus protecting the citizens from sun and dust in the summer, and

from cold and mud in the winter. Water channeledinto the cities via aquedects

sprang from the fountains, and a fine, well maintained network of roads and

stone bridges connected the cities on the peninsula. Dozens of ancient cities

in Western and Southern Anatolia, portions of them almost as they were in

Roman times, fill visitors with awe.

The First Christian State in the World

The Byzantine Empire (330-1453 A.D.)

Byzantine art was born in Anatolia at the end

of the Roman era. As the Roman art of sculpture and architectural decoration

entered a period of decline toward the end of the 3rd century, new life was

breathed into them by early Christian practitioners of both arts. One might

say that early Christian and Byzantine art were an expressionistics rendering

of Roman themes; where architectural space was concerned, they represented a

whole new approach.

For

two and a half centuries, from 300 to 565 A.D., Constantinople (Istanbul) was

the leading city of the world in art and culture. The most brilliant time for

the early Christian era was the reign of Justinian (527-565). Hagia Sophia, a

centrally domed basilica, was built perior to this (532-539), and is the

masterpiece of Byzantine art, one of the most famous works in the entire

world. For

two and a half centuries, from 300 to 565 A.D., Constantinople (Istanbul) was

the leading city of the world in art and culture. The most brilliant time for

the early Christian era was the reign of Justinian (527-565). Hagia Sophia, a

centrally domed basilica, was built perior to this (532-539), and is the

masterpiece of Byzantine art, one of the most famous works in the entire

world.

The best preserved Byzantine religious

buildings are Hagia Irini Church (6th and 8th centuries), the Basilica of St.

John (Justinian's reign) and the Church of Mary (4th and 6th centuries), both

in Ephesus, and the Alahan Church (5th and 6th centuries) in Southeastern

Anatolia. From the Late Byzantine era the best preserved and finest works are

St. Mary Pammakaristos (1310) next to Fethiye Mosque, and Kariye Mosque, that

is to say the Chora Church, both in Istanbul. In the latter two buildings, the

multidomed ceiling harmonizes beautifully with the walls and their

three-staged arches.

The first people to dwell in all of Anatolia

were the Turks. The Hittites, Phrygians and Greeks lived in only part of the

peninsula.

The Turks arrived in Anatolia from Central

Asia by way of continual migrations and incursions, and through their policy

of tolerance in government earned the love of the Indo-European peoples living

on the peninsula.It was the Turks who adopted Islam, and on this basis mingled

with the local peoples starting in 1071. The passage of nine centuries has

resulted in present-day Turkey.

Until recently it was thought that

contemporary Western civilization was based on the Greeks, but archaelogy and

history now show that it goes back rather to beginnings in western and

south-western Anatolia.

Historical Ages of the Works Displayed

Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Ages

During these ages between 600000-8000 B.C.

and also named as the Old Stone Age and the Middle Stone Age, man survived by

gathering and they Middle Stone Age, man survived by gathering and they made

tools and weapons of stone. Important finds related to this period are in the

settlement centers in Karain, Kadiini, Okuzini, Beldibi and Belbasi in Antalya

region and in Sehremuz near Adiyaman, in Duluk near Gaziantep.

Neolithic Age

The distinguishing characteristic of this age

between 8000-5000 B.C. is the start of production, farming and animal

husbandry. Man in this age, left the caves and began to live in stone and

mudbrick dwellings. The most important finds related to the Neolithic Age in

Anatolia are in Catalhoyuk.

Chalcolithic Age

In this age covering the years between

5000-3000 B.C., man started to make pottery of baked clay and to decorate the

ceramics. This is understood from the excavation finds in settlement centers

such as Hacilar, Can Hasan, Yumuktepe, Gozlukule, Beycesultan, Alisar,

Alacahoyuk. Relations with Mesopotamia developed by way of the rivers Tigris

and Euphrates.

Early Bronze Age

The people who lived in Anatolia between

3000-2000 B.C. acquired the knowledge to produce bronze by combining copper

and tin, and they started to produce weapons, pots and pans and ornaments from

this alloy. The most important finds of this period are in Troy and Alacahoyuk.

During this era when the pottery wheel was put into use, the Anatolian man

learned to make statuettes of baked clay, marble, alabaster, bronze and gold

with both religious and decorative purposes.

Middle and Late Bronze Ages

This age covering the period between

2000-1200 B.C. is the era when trading was prevalent and the first written

records were made in Anatolia. The trade relations with various Mesopotamian

states and especially with Assyria, caused cultural and artistic interaction

and as the result of this interaction an Anatolian style with characteristics

of its own was created. The political power dominating this age was the

Hittite Emire. The typical characteristics of the age can be understood from

the excavation finds in Bogazkoy-Hattusa in Central Anatolia, and the ceramics

found in Troy, Western Anatolia prove the relations with the Mycenaean

civilisation.

Late Hittite City States

Small kingdoms who were the inheritors of the

Hittite Empire between 1200-700 B.C. carried on the Hittite tradition for a

while. However, this tradition gradually lost its own characteristics and

began to take new forms under the influence of the Aramaean's who moved into

the region, the Assyrians in the south, the Phrygians in the west and the

Urartians in the east.

The Urartian Kingdom

The Urartion Kingdom (900-600 B.C. which

established a developed civilisation on the area between the lakes of Van,

Urmiye, Gokcegol and Cildir, on the one hand left many documents written in

cuneiform and hieroglyph and on the other hand they contributed a great deal

to the Near Eastern art in architecture and engineering fields. The Urartians

who knew how to make use of natural forces by constructing dams and water

channels, also made a great development in the field of metallurgy.

The Phrygian Kingdom

During the Phrygian Kingdom (700-550 B.C.)

founded in the area between the northern Kizilirmak and Sakarya rivers,

woodworks, ceramic production and the objects made both for daily use and for

artistic purposes showed a great development. The capital of the Phrygian

Kingdom was Gordian, their chief goddess was Kybele and their most famous king

was Midas.

The Lydian Kingdom

The most important historical characteristic

of the Lydian Kingdom which was founded in Western Anatolia (700-550 B.C. was

the coining of the first metal coin in the world.

Ionian City States

The settlement centers founded in Western

Anatolia since 3000-2000 B.C. carried on relations with the Aegean world on

one hand and Anatolia on the other. The resulting cultural and artistic

interaction created the Orientalising style during the 8th and 7th

centuries B.C. This development, influenced the art of the following Archaic

and Classical ages.

The Persian Period and Graeco-Persian

Style

After the Lydian Kingdom was defeated by the

Persian king Cyrus, Anatolia came under the control of the Persians. The most

important works remaining from this period which lasted between 546-334 B.C.

are the famous Royal Road and the Halicarnassus Mausoleum.

The Hellenistic Period

This period which started by the defeat of

Persian dominance by Alexander the Great lasted between 330-30 B.C. A major

part of Anatolia came under the power of Pergamon after Alexander's death.

Pergamon contributed a great deal to the world history of culture and art in

the field of sculpture and by using parchment as a writing material.

The Roman Period

When the last king of Pergamon bequeathed his

kingdom to Rome, Anatolia came under the sovereignty of Rome. In the beginning

of this era which laster between 30 B.C.-330 A.D. the influence of the

Hellenistic style preserved its being in the Anatolian art and culture.

Although the influence of Roman art and culture was later imposed, the

traditional culture nevertheless survived and regional characteristics in art

developed. The most important cultural and artistic centers of the period were

Aphrodisian and Perge.

The Byzantine Period

The Byzantine era which lasted for nearly a

thousand years between 330-1453 A.D. was greatly influenced by the former

civilisation accumulation. When regional characteristics were combined with

the influences of Christianity, new styles were created. Istanbul renowned

worldwide as a cultural and artistic center, played an important role in

turning over the art of the archaic ages to the medieval age. The Byzantine

architecture which reached its summit with Hagia Sofia, gave its most

beautiful examples with fortresses, water archways and cisterns, bridges and

places. The Byzantine era also witnessed great developments in sculpture,

mosaic, gilding and ornaments.

Seljuk Period

This period which started by Alpaslan's

victory (the nephew of Seljuk Bey, founder of the Seljuk dynasty) in 1071,

laster until 1300 A.D. After the collapse of the Great Seljuk Empire in 1157,

the Anatolian Seljuks centred their state in Konya. This state which had its

most glorious period during Sultan Alaaddin Keykubat's reign, gained supremacy

over Anatolia. Roads, bridges, caravanserais were built during this period.

The Seljuks, while having close links with Persian maintained their own art

and culture brought from Central Asia by the Turkish migrations. They created

the Turkish-Islamic culture by the synthesis, of the Anatolian cultural

accumulation and other cultural influences. The mosques, medreses, baths

formed the finest examples of the period in architecture. Developments in

various fields of art was so great as to influence the following ages. One of

the greatest contributions of the Seljuks to the Anatoian civilisation was the

introduction of knotted-carpet making.

The Ottoman Period

This period which lasted between 1299-1923,

is the era when not only Anatolia but also the land on the European side was

attached to the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman art based on the Turkish-Islamic

and Anatolian artistic synthesis created during the Seljuk period, developed

further under the direction of the palace by adopting the new techniques of

the age and created a characteristic Ottoman style. However, the

Westernisation trend of the 18th century, gave way to the Western

influence and consequently the traditional Ottoman art gradually lost its

impact. The Ottomans, besides all the other fields of art also proved their

superiority in architecture by mosques, tombs, medreses, libraries, covered

bazaars, baths, places, caravanserais, kiosks, mansions, aqueducts and

bridges. The most famous architect of the Ottoman period was Sinan and the

finest example of his work is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne.

Source:

Antika; The Turkish Journal of Collectable Art,

September 1985, Issue: 6

Anatolia: The Last Ten Thousand Years

Bluffer's Guide to the Anatolian Iron Age

By Roger Norman / Turkish Daily News

This is the second Bluffer's Guide, and takes

over more or less where the first one ended, at the close of the Anatolian

Bronze Age and the time of the upheavals of the 13th and 12th centuries B.C.

caused by largescale migrations in the Aegean region. The end of the 13th

century saw the end of the Hittite Empire that had dominated Anatolian history

for 500 years.

When to date the end of the Iron Age is a matter of taste, since in some ways

it can be said to be still continuing. For the purposes of this guide, the end

of the 6th century B.C. has been somewhat arbitrarily taken as the terminal

date, on the grounds that the 5th century onwards can better be considered

under the heading of Anatolia in classical times. We are thus dealing

approximately with the period 1200 to 500 B.C. As in the Bronze Age, the

center of power in the region remains the Near East, first in the shape of the

vast Assyrian Empire of Sargon II, afterwards with the emergence of the Medes

and Persians. Phrygia, and then Lydia, were the dominant Anatolian powers, and

Greek cities were starting to appear on the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts,

and, later, on the Black Sea. Cyrus the Great died in 530 B.C. and Croesus of

Lydia around the same time.

ARMENIANS -- A tribe, possibly of PHRYGIAN origin, which gradually occupied

the region of URARTIA towards the end of the 7th century. The position of a

kingdom sandwiched between the MEDES, the ASSYRIANS and whoever was the

dominant power in Anatolia proper guaranteed a chequered career for the first

Armenians, and for most of their successors. Armenia was to be ruled

successively by Medes, Persians, Seleucids, Romans etc. etc.

ASSYRIANS -- After a period of relative

decline in the 12th and 11th centuries, the Assyrian Empire not only recovered

but expanded rapidly, especially during the reign of Sargon II (722-706), so

that by the end of the 8th century B.C., Assyria comprised the whole of

present day Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Palestine and extensive territories in

present day Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Assyrian kings even ruled in Egypt

for 20 years in the mid 7th century. The empire collapsed with impressive

speed, however, during the final decades of the 7th century, defeated by a

coalition of MEDES and Babylonians. The Assyrian capital Nineveh fell in 612.

CIMMERIANS -- One of the

"destroyers" of historical record and, like others before and after

them, originating from somewhere in the broad steppes of southern Russia.

Swept into Anatolian history at the end of the 8th century, first harrying the

URARTIANS, then destroying the Phrygian capital GORDIUM in 695 and burning

Lydian SARDIS 50 years later. Always described as historians as advancing in

"hordes", technically an anachronism, since the word horde comes

from the Turkish <ITALIK ordu ITALIK> meaning army.

CROESUS -- Lydian king who reigned c. 560 to

547 B.C. Like the Phrygian Midas, a byword for great wealth, possibly because

the LYDIANS were the first to mint coins. Croesus was the subject of the

famous dialogue with Solon related by Herodotus. In reply to Croesus' leading

question "Who is the most fortunate of men?", Solon irritatingly

replied by naming various unknown and defunct Greeks, making the point that no

man could be called happy until he was dead. It was also Croesus who was

fooled by the ambiguous reply of the Delphic oracle -- "If you attack,

you will destroy a great nation". It turned out to be his own, and

Croesus became an (honored) captive of the Persian king Cyrus. Croesus has

come down to us as a very human and rather sympathetic character, thanks

largely to Herodotus. History proper starts somewhere here, one might say.

CYBELE -- The chief Phrygian divinity and

their version of the Anatolian mother goddess. She was suckled by wild

creatures as an infant, ministered to as a deity by castrated priests and her

cult was apparently characterized by frenzied orgies. A symbol of fertility,

often depicted as pregnant, sometimes many-breasted. Atys was her

omprehensively defeated (although somewhat unfairly, some would say, because

Cyrus apparently used the smell of his pack camels to deter the Lydian

cavalry) in 547 B.C. Sardis was taken and Lydia became a Persian satrapy.

MEDES -- An Iranian tribe who first appear as

the Mada and start threatening the power of Assyria in the 7th century.

Together with Babylonian forces they destroyed Nineveh in 612 and soon

afterwards took control of URARTIA. They were later defeated by the Persian

King Cyrus and were incorporated into the empire of the PERSIANS. The Greeks

tended to refer to the Persians as Medes and Cyrus as "the Mede". In

the later Persian Empire, the Medes were associated with the Magi, a

sacerdotal caste who followed the teachings of Zoroaster (Zarathustra).

MIDAS -- Known as Mita to the Assyrians and

Egyptians. Famous in legend for the "Midas touch" which turned

everything, even his food, to gold. Yet oddly there was no gold found in the

immense burial mound near GORDIUM that has come to be known as Midas' tomb.

There were however, a large number of wonderful bronze cauldrons and other

vessels which can now be seen in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in

Ankara. Actually, there is a second so-called Tomb of Midas, an intriguing

temple, possibly dedicated to CYBELE and to be found some 60 kilometers

southeast of Eskisehir. It consists of a huge facade sculptured on the living

rock. Midas himself was probably the last of the independent PHRYGIAN kings

and is said to have committed suicide after the defeat by the CIMMERIANS.

MOPSUS -- A Greek by the name of Mopsus has

the honor of being the very first figure of Greek legend to be authenticated

as a historical personality. (Remember that there is still no <ITALIK proof

ITALIK> that there were ever such people as Agamemnon or Achilles.) Legend

said that one Mopsus wandered the Anatolian peninsula after the fall of Troy

and ended up founding Greek colonies in Pamphylia and Cilicia (on the

Mediterranean coast). He appears in a Hittite document with the unappealing

name of Mukshush and also in an inscription at Karatepe in Cilicia. He is said

to have founded Aspendus, Phaselis and Mopsuestia.

NEO-HITTITES -- Remnants of the Hittites,

mixed with Hurrians, Hattians and others, who occupied a series of city states

in the northern regions of present day Syria and southern Turkey. The art and

architecture of the Neo-Hittite cities owe a good deal to Hittite traditions.

Carchemish and Zincirli, close to the present day Turco-Syrian border are the

best known of these.

PERSIANS -- An Iranian people who probably

arrived in the region of present day Iran during the 8th century B.C., a

little later than the MEDES, whom they later defeated and assimilated. It was

under Cyrus the Great that the Persians began to build the great empire that

was to be the dominant power of the Near East on and off for nearly a

millennium. The early period of Persian glory is usually referred to by the

name of its ruling dynasty, the Achaemenids, who were overthrown by Alexander.

(They were succeeded in turn by the Seleucids -- named after Alexander's

general Seleucus, the Parthians -- who fought the Romans over three centuries,

and the Sassanians -- who were finally defeated by the Arabs.) Cyrus took

Lydia and Babylonia; his son Cambyses occupied Egypt; and Darius I, who became

king in 486 B.C., was responsible for introducing a gold coinage, building a

huge network of roads -- including the Royal Road from SARDIS to Susa and

fostering commerce throughout the empire.

PHRYGIANS -- Federation of tribes who moved

into Anatolia from Eastern Europe during the last century of the Bronze Age

and who established a powerful kingdom centered on GORDIUM which included Troy

and Hierapolis. Replaced the Hittite Empire as the dominant force in central

Anatolia, building modest walled towns on the ruins of the old Hittite cities

-- at Bogazkoy, Alaca Hoyuk, Kultepe and elsewhere. Came up against Sargon II

of ASSYRIA in the 8th century and were wiped out by the fierce CIMMERIANS at

the beginning of the 7th century. Phrygian inscriptions remain unintelligible

and the reputation the Phrygian people have left behind them makes strange

reading. Stubborn, effeminate, servile and voluptuous according to various

Greek readers, they were famous as makers of grave and solemn music and also

for the wearing of a peculiar conical cap which was later worn by freed Roman

slaves and thus became a symbol of liberty to the French revolutionaries of

1789. Phrygia was also known among Greeks as a land of fabulous wealth (see

MIDAS).Their Chief divinity was CYBELE.

SARDIS -- Lydian capital, situated in the

broad and fertile valley of the Gediz Cayi. There's not much left now of the

Lydian city, although American excavators claim to have found the remains of

the first ever mint (see CROESUS). Ten kilometers to the north lies Bin Tepe,

the Lydian necropolis, where there are scores of burial mounds dating from the

great age of the Lydian kingdom. The largest of these, the Tomb of Alyattes

(father of Croesus), took ten minutes to ride around according to the

nineteenth century traveller W.J. Hamilton.

URARTIANS -- Possibly a Hurrian people, since

their language is closely related. Settled the area around Lake Van and

established a kingdom that included Mt. Ararat and the headwaters of the

Tigris and Euphrates. First mentioned in ASSYRIAN texts in the 13th century

B.C., reached their zenith three or four centuries later when they built a

characteristic series of massive hill fortresses in the region. Came into

conflict with the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century B.C. and disappeared from

history somewhat mysteriously in the 6th century at which period they were

replaced by the ARMENIANS. Urartia is sometimes known as the Kingdom of Van,

or the Vannic kingdom.

Anatolia: The Last Ten Thousand Years

Art is an indispensable feature of communal

life, quite irrespective of the structure of the community. Every change in

form and colour to be found in nature, in the sky or in the waters,

constitutes a source of artistic inspiration in man. In a sense, art lies at

the root of all tradition.

Art exists, at least to some degree, even in

periods of political upheaval or stagnation. The reason is obvious. Man, like

nature, is productive and creative. It is thus impossible to keep man bound

and inactive in face of the myriad forms and colours of nature. Even if his

hands were bound he would express himself in songs and poems.

The phenomenon we know as progress is the

result of a certain synthesis. The products of the fusion of art with the

habits and preferences of everyday life remain to future generations as

master-pieces of tradition.

Have you ever wondered how many drawing have

been made of a leaf?

How can we tell how many times the lines of

joy or grief on the human face have formed the subject of a drawing? As

infinite in number as instances of joy and grief themselves are infinite.

Even today there are scores of communities

and societies of which we know absolutely nothing! Where, we wonder, are the

sources of their poems, their songs, their pictures and decorations concealed?

And to this series of questions we can add

another -a question that is continually cropping up-the question of modernity.

We tend to think that everything produced in

the age in which we live is art, and that all the art we produce is modern and

original. Art cannot begin by repudiating the master-pieces of the past. No

matter what names we apply to the objects we create, and no matter how

fantastically we behave, it doesn't necessarily mean that we are modern and

progressive.

Art is a process of reduction. The power to

reduce to the simplest terms.

Tens of thousands of years ago anonymous

craftsmen using the most primitive tools produced works of art that could well

have been produced today. What name would you give to the following, for

example?

"Even running towards you is cool

water for thirst."

Or to this?

"This is a grave, there is no corpse

within it.

This is a corpse, there is no grave around

it.

This corpse is buried in itself."

Or this?

"You are in love with your own

beauty,

It is as if held a mirror to your face."

What period do you think these little

extracts belong? We certainly enjoy reading them. Could they all be the work

of contemporary poets?

The writer of the first couplet was an

Egyptian poet who lived four thousand years ago. We know the name of the

second writer. He was called Agation and lived in the Byzantine period.

The third couplet is by Omer Khayam.

And let us not forget Yunus Emre, who

could write lines like:

"I saw my moon on the ground.

The rain falls from the ground upon

me."

There are so many poems, paintings, statues

and decorative compositions created by artists who lived thousands of years

ago that still remain fresh and alive today.

But please don't inter from this that there

are no modern artist whose works will survive. The important thing is not to

boast of being modern, of producing work for the future. Since when has

incompetence and ineptitude been regarded as art?

Another disease lies in the rejection of all

the art and architecture of the past.

Universality is difficult to achieve. One

must mature and ripen, like Yunus in the dervish convent. But modern man is

always in a hurry. And he is also a chatterer.

Let us not forget that we till the same soil

as previous civilisations and breathe the same air. What is more, all our

skills are based, like those of our forefathers, on man and nature. In other

words, there is not a square inch of soil that has been left undisturbed. And

yet the soil of Anatolia goes so deep that there must be thousands of

unexamined, unheard of, unseen poems, statues and works of art awaiting the

interested researcher.

And what will happen when all these are

unearthed?

It was Shakespeare, not myself, who said, "The

past is a preface to the present."

Anatolia

possesses ten thousand years of history. Some of this is underground, some of

it above. During this long adventure of ten thousand years there have been

periods of war and periods of peace, but people and communities have always

gone out in pursuit of beauty and art. The source of beauty and art lies in

man and the soil. That is what I meant when I said that "there is not a

square inch of the soil that has been left undisturbed." Every community

has its poet of hope, love and grief. And I doubt if they differed very much

from the poets in our own society. They also roamed about, sang their songs,

set up a home and tried to penetrate to the essence of the real. But most of

us are quite unaware of all this. We regard the 20th century as the sole

reality! Anatolia

possesses ten thousand years of history. Some of this is underground, some of

it above. During this long adventure of ten thousand years there have been

periods of war and periods of peace, but people and communities have always

gone out in pursuit of beauty and art. The source of beauty and art lies in

man and the soil. That is what I meant when I said that "there is not a

square inch of the soil that has been left undisturbed." Every community

has its poet of hope, love and grief. And I doubt if they differed very much

from the poets in our own society. They also roamed about, sang their songs,

set up a home and tried to penetrate to the essence of the real. But most of

us are quite unaware of all this. We regard the 20th century as the sole

reality!

The

question of the new and the modern all comes down to this, and it is a

solution to this question that all the most distinguished scholars of our day

are seeking. Unanswered questions remain, concerning thousands of works

produced in Ancient Egyptian, Hittite, Phrygian, Urartian, Ionian, Byzantine,

Seljuk and Ottoman times. The

question of the new and the modern all comes down to this, and it is a

solution to this question that all the most distinguished scholars of our day

are seeking. Unanswered questions remain, concerning thousands of works

produced in Ancient Egyptian, Hittite, Phrygian, Urartian, Ionian, Byzantine,

Seljuk and Ottoman times.

Many of these questions rest in the soil of

Anatolia. You may seek out the answers to these or you may simply ignore them.

But everyone loves gossip. There was gossip thousands of years ago.

Everything begins with a symbol. In primitive

art the symbol acts as a guide. A system of communication. Gradually this

symbol becomes an indispensable feature of ritual worship in both monotheistic

and polytheistic religions.

Who will transform these symbols into

sketches, idols or icons, or into words or music for religious ceremonies? Let

he who feels he has the necessary power step forward!

Behold the anonymous artists and master

craftsmen!

The Anatolian Adventure

The inhabitants of Anatolia who lived through

the great Neolithic revolution ten thousand years ago attempted to solve the

change in nature by adopting a sedentary life. The finds yielded by the

excavations in the village of Hacilar near Burdur were the generous gifts of

the rain, the soil, the daylight, the water, the sun and man himself. They

were the precursors of civilisation.

The finds from Hacilar, Çatalhöyük, Kültepe

and Çayönü may well be described as a world of symbols.

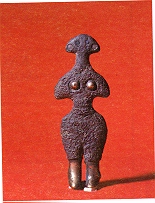

Everything imaginable is to be found in this

world of symbols. Murals, seals, jewellery, figurines of the mother goddess.

Men who had embarked on agriculture and cattle-raising must obviously have

feared the forces of nature. But here the question is: Why did they feel this

need for the beautiful?

No one could ever deny the beauty of form and

line possessed by the seals and jewellery.

It

is very understandable that special importance should be given to seals

symbolising property and ownership of property. Seals quite distinct one from

the other, with their own particular form and line. But what aesthetic

aspiration can explain meticulous attention to line and form in the

earthenware vessels from which they drank their water or sipped their wine,

and in which they sometimes stored the produce? The conscious conception of

art was a phenomenon that was to evolve thousands of years later. As for the

pursuit of the beautiful, they may be the answer to our question. It

is very understandable that special importance should be given to seals

symbolising property and ownership of property. Seals quite distinct one from

the other, with their own particular form and line. But what aesthetic

aspiration can explain meticulous attention to line and form in the

earthenware vessels from which they drank their water or sipped their wine,

and in which they sometimes stored the produce? The conscious conception of

art was a phenomenon that was to evolve thousands of years later. As for the

pursuit of the beautiful, they may be the answer to our question.

But now we are confronted with the world of

symbols in quite a different form. Heralds of a totally new world are to be

found in centres such as Alacahöyük. Horoztepe and Hasanoglu.

The men of that period seemed to be rebelling

against nature.

I stubbornly insist on asking the question

"What example of simple figural abstraction do you wish to see?"

The Horoztepe figurine of a mother and child?

The statuette of a goddess encircled with gold bands? The gold goblet with

grooved neck found in the royal graves? The twin idols holding each other by

the hand with their fertility transformed into buttons and perforations? The

bull and stag figures freely symbolising nature and the universe?

Fear and devotion could never produce

anything so beautiful. Leaving aside the technique employed in shaping the

bronze or the gold, what fear or anxiety could give rise to such abstraction?

Let's leave aside the period and provenance.

Which of them are not contemporary? Which of them are not contemporary? Which

of them conflict with the contemporary approach to sculpture?

Of those who share the same soil thousands of

years later the inhabitants of Alacahöyük, Horoztepe or Alisar for

example-which of them can be said to share the same evolution?

The statues and utensils of copper, lead,

bronze or gold must be regarded as memorials of the point in evolution

attained by human thought.

But this is not the end of the story of

polytheism in Anatolia. We are still, as it were, at the beginning. Now we

have the Anatolian woman, adorned with her jewellery, tidying up her hearth

and home. At Troy, what is more!.. Or were they preparing themselves a

different future with their ear-rings, gold brooches, idols and lapis lazuli

symbols?

In my opinion, the only aim of the artist in

those days was that the objects he created should please. If we had been in

their place, God knows what we would have done with all our advertisers and

publicity agents!

Who could have guessed that the old

concentric, geometrical forms would still be found in the 20th century

Anatolian kilim? It is as if it had all been loaded on to a caravan thousands

of years ago!

Beyond The Hittites

To express it in the simplest terms, a work

of art consists of line, form and interpretation. So many lines are timid and

hesitant, so many colours are dull and insipid when compared with the beauty

of nature.

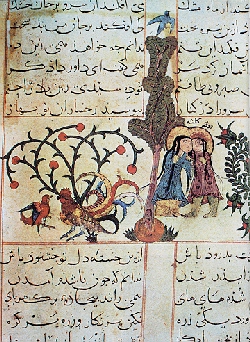

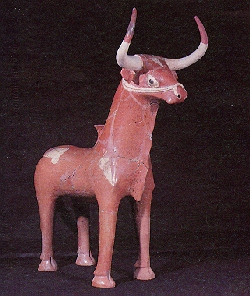

The

Ankara Museum of Anatolian Civilisations contains two clay figures of the

sky-god in a chariot drawn by bulls. The

Ankara Museum of Anatolian Civilisations contains two clay figures of the

sky-god in a chariot drawn by bulls.

Have you ever looked at them closely? I am

proud to say that I have actually handled them, with the greatest reverence. I

thrilled with emotion. What craftsman, or what craftsmen created these

statuettes two or three thousand years ago? They would appear to be utterly

free of all sin. They were so lovable that I felt like embracing them. Their

line and colour and interpretation might well have been the work of a

distinguished contemporary artist!

And here is a vase from the Hittite

Principalities discovered in the Kültepe excavations. It has all the

appearance of being produced in the 20th century. The body, widening out from

a narrow base with all the mastery of geometrical form, ends in a beak

stretching out to infinity. What are the two small projections on the smooth

surface of the body? Might they be symbols of the fertility of the mother

goddess?

I have no idea what the Hittite craftsman was

seeking to create, but today I look upon it as a statue.

This Hittite potter is challenged by the

craftsman who created the gold pitcher found at Horoztepe, leaving questions

for the world of symbols in its circles, spiral grooves and swastikas. This

fantastic specimen is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Line is of prime importance in painting,

sculpture, music and architecture. The path traced by the line might well be

accepted as the path traced by art.

The various communities that contributed to

the Anatolian communities lent each other a helping hand in both peace and

war. It is enough just to follow a single line traced on the soil, to observe

the changes it undergoes and the meanings with which it was endowed. In this

line you can observe all the destruction, all the annihilation, all the

revival and resuscitation that occurred around it.

If you are a community that asks questions

you can find all these questions asked thousands of years ago.

Let us not boast. Reality is not confined to

the one age that is reality to us. They too were fully aware of the natural

and human reality. We must admit to only one true reality; the reality of man

and nature in there partnership and rivalry. Communities find their identity

in this reality, and it is in art alone that this reality is enshrined.

Bulls, Men And Decorative Design

Any mention of King Midas immediately brings

the Phrygians to mind. But before turning to the Phrygians and the Mother

Goddess they took under their protection I should like to make one further

remark about the Hittites. In the Hittite Kingdom the king was not the

representative of God on earth as he was in the East and in the Indo-European

countries.

According to the customs and traditions

prevailing in the first quarter of the second millennium a women, on getting

married, was neither purchased by nor handed over to the man. Undoubtedly,

many examples of their laws which are still valid today must also have exerted

an influence on art. Concrete evidence of this is to be found both in love

letters and commercial correspondence.

The Urartu civilisation that reigned for

three hundred years in the Van region was characterised by its skill in

metalwork. The bronze artefacts they produced have been found in Phrygia,

Samos, Delphi and Olympia. This shows how long and how extensive is the path

traced by art.

Midas, the Phrygian King!

When Midas ascended the throne in 738 B.C.

his own nation occupied the lands of the Hittites. It is a matter of no small

significance that a legend created by the folk should describe how King Midas

preferred the melodies produced by the pipe of Pan in the musical contest

between the gods Pan and Apollo, and that Apollo should have punished him by

giving him the ears of an ass.

For at that time Phrygia was renowned for its

music.

Furthermore, the goblets manufactured on

Phrygian soil and the drinking vessels in the form of eagles and rams were

exported to Greece, in the same way as Phrygian music had influenced Hellenic

civilisation.

The two bronze cauldrons found in the grave

of Midas at Altuntepe and Gordian come to mind, one adorned with bull's heads,

the other with unsmiling human faces. In each case I would define the

workmanship as absolutely contemporary. And yet both of them are products of

the old Urartian civilisation.

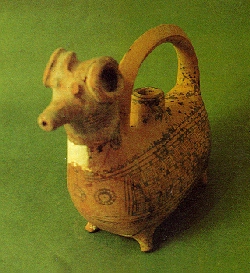

In the drinking vessels consisting of animal

figures fashioned in clay by the Phrygians there is a whole unsmiling world.

It had been so since the time of the Hittites. Or even since the first

introduction of metal.

All these specimens demonstrate the utmost

skill in the use of line. Even the simplest Phrygian bowl or utensil displays

a mastery of line and volume.

Every one of the artefacts produced in the

Mesopotamian tradition display the stamp of their own particular period. It

should not be forgotten that the floors of the houses in Gordion are adorned

with coloured pebbles.

If we leave Troy, an important settlement

from the Bronze Age onwards, and continue down to the shores of the Aegean we

shall encounter the Lydians, Carians, lonians and Lycians.

These were all dominated by a Mediterranean

culture that combined a polytheistic religion with a monumentally style of

architecture.

Two thousand five hundred years ago, in 585

B.C. to be precise, Thales foretold an eclipse of the sun a full year before

the event. This scientific achievement exerted a great influence on the Turks

and the Arabs, who laid the foundations for the scientific progress that

flourished in Europe during the Renaissance and in the 19th and 20th

centuries.

Miletus and the Ionian cities were centres of

poetry and the arts, while the temple and statues of Artemis at Ephesus

continued the tradition of the "Mother Goddess" on Anatolian soil.

The influence of Ionian architecture, first felt in Athens, became increasily

pervasive in Europe and America up to the beginning of the 20th century, and

traces of it are still to be seen in contemporary monumental architecture. In

parenthesis we may mention that Aphrodisiacs has always been a city famous for

its sculpture.

On entering the ancient cities of Kaunos,

Xanthos, Patara, Letoon, Phaselis or Termessos you will find yourself in a

completely different world. But again it is a question of houses, with a

monumental decoration of spirals and meanders, as from the time of the

Hittites onwards. Only the lives of the builders and the period to which they

belong are different.

An examination of tradition allows us to see

the lines of the civilisations before our own. Doesn't the single path taken

by the Mother Goddess, the goddess of beauty and fertility, Kybele, Artemis

and Aphrodite, suffice for the aim attained by art.

"My birthday will be celebrated every

month and every year. In these ceremonies, the gods, the head priest and

myself will, on my own authority and the authority generously given by the

laws, don Persian costume and place golden wreaths on the statues of the gods,

my ancestors and my self. For each one of us a great abundance of incense will

be burned. Due sacrifices will be made. The sacred tables will be loaded with

the finest foods and wines. My people will gather here eat their fill and

rejoice."

So commanded King Antiochos of Commagene two

thousand five hundred years ago. I have already quoted this noble and generous

decree in a number of different contexts. I keep coming back to lovely things

of this nature. The more often we remind ourselves of such things the better.

We live amid the remains of a great

sultanate, a magnificent sultanate that harbours a host of cities and

civilisations to which we have not, so far, referred.

Byzantine, Seljuk, Ottoman

So

many legends are enshrined in the world that extends from Cappadocia to the

Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors at Sultanahmet and the frescoes and

mosaics of Kariye and Ayasofya that one becomes utterly confused and

bewildered. One is overwhelmed by the luxuriant fertility of the civilisations. So

many legends are enshrined in the world that extends from Cappadocia to the

Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors at Sultanahmet and the frescoes and

mosaics of Kariye and Ayasofya that one becomes utterly confused and

bewildered. One is overwhelmed by the luxuriant fertility of the civilisations.

I see a picture before me. It is probably by

Mondrian. It draws me into a labyrinth of yellows, greens, blues, reds, blacks

and whites.

I read the label beneath the picture. 15th

century, Topkapi Palace Museum

It must be a leaf from an album. And it's

Seljuk.

What does this all mean? Let's put our heads

together and think about it. Is it line that is infinite, or is it the

civilisation that produced the creators of the line? Or both? Or is it a case

of man coming to terms with himself in the midst of empires, catastrophes,

extinctions, joys and sorrows?

There are so many examples of this on the

soil of Anatolia a soil on which the unknown far exceeds the known. And should

we rush to a hasty conclusion both on what existed before us and what we

ourselves have created?

The creations of every age necessarily differ

from those of the previous ages. But we must recognise that the 20th

century is not the sole possessor of truth and reality.

I ask again. What is meant by modernity?

Beware of assuming the infinity of man and

nature.

The best thing is to lose oneself in the

decorative designs of the great 16th century master Karamemi or the

saz yolu compositions of Shah Kulu, forced to leave Tabriz for Amasya at the

beginning of the 16th century.

The choice is yours.

Source: Türkiyemiz,

Culture and Art Magazine, October 1991

By : Gürol

Sözen

Anatolian Jewelry

Jewelry of the Hittites of a Thousand

Gods

At the beginning of the 2nd

Millennium B.C., Hittite art was born with the Assyrian trading colonies

during the period of the Hittite principalities. This art acquired a

distinctive character integrating the native Anatolian Hatti culture with the

cultures of Northern Syria and of Mesopotamia and during the Royal and

Imperial ages of the Hittites. This art turned into a religious palace art. It

was during this period that the production of large dimension plastic works

such as orthostats and cliff reliefs began, examples of which we do not

previously encounter in Anatolia.

In addition to the Procession of the Gods in

relief at Yazilikaya, an open-air temple near the capital city of Hattushash

(modern Bogazkoy), the lion and sphinx reliefs on the city gates at Alacahoyuk

are the most impressive examples of this art. Just as they are visible in this

gigantic art, the influences of the art of the imperial religious cult also

made themselves clearly felt in small plastic production as well (Figure 1,

a-b).

There are few pieces of jewelry which have

managed to survive from the Royal and Imperial Hittite Periods down to the

present day. Gold rings without stones were also used as seals. On some

examples of these we find figures worked in by an engraving technique (Figure

2), and in others we find helical motifs surround by cuneiform and

hieroglyphic script (Figure 3).

Figures of gods and goddesses (Figure 1.b)

done in cast gold, silver, or bronze, or produced by means of carving

techniques from materials such as ivory or quartz are also examples of

amulets, which were part of the religious art. Ivory, in addition to being

used in jewerly, was also worked for use as a decoration for furniture and

similar wooden objects.

Popular Hittite Jewelry

At archaeological excavations carried out in

recent years near Gordium (Machteld, Melling, 1956) and Afyon Yanarlar (Emre,

1978), materials acquired from two Hittite graves indicate the existence of a

popular art a Hittite jewelry in addition to that of the palace. Among these

finds are necklaces made of sea shells, which are examples of a tradition

continuing from Neolithic times. These widely divergent types of sea shells

found in great profusion in excavations of Assyrian city (Figure 5) were most

probably used in popular jewelry as charms or as fertility magic.

One encounters the metal needles found in the

graves mentioned above for the first time in the Bronze Age in the Royal Grave

at Alacahoyuk (Figure 6), and the Troy and other contemporary settlements. Use

of this material continued with the Hittites.

Lost Graves and Undiscovered Jewelry

The quartz figurine of a god at the Adana

Museum shows that form the Early Bronze Age onwards, the Hittites were quite

successful in working hard gems. Nevertheless there are a number of reasons

why one does not encounter the typical Early Bronze Age high-quality gem and

chased metal jewelry, found in the Hittite kings and of the nobility have not

been located. In addition, it should not be forgotten that the looting by the

Muski tribes coming down from the strats and invading Anatolia in the 1200th

Century B.C. was so thorough as to erase the name of the Hittites from

history.

With the destruction of the Hittite Empire,

Anatolia entered upon a Dark Ages of three to four hundred years duration,

during which time small states emerged. The contributions made by these to the

art and techniques of jewelry may be summarised as follows.

From Empire to City-State

The Late Hittite Principalities, which

developed in the Southeastern Anatolia-Northern Syria region (1200-700 B.C.),

on the one had continued the art of the Hittite Empire, while on the they

other were influenced by Babylonian, Assyrian, and Aramaic art. We know from

their orthostats, cliff reliefs, and statutes that they too were excellent

masters of stone work. Similarly the large-dimension works of this period

provide information about men's and women's jewelry. The famous relief of

Ivriz and the statue of King Tarhunza show that the men of the age also made

great use of jewelry (Figures 7, 8). By means of trade routes, late Hittite

art had considerable impact on the developing art of Ionia and Lydia in

western Anatolia.

The Urartus-Master Jewelers of Eastern

Anatolia

The Urartu State, which grew up around the

shores of Lake Van between 900 and 600 B.C. created an extremely theocratic

style of palace art, and at the same time remained to a large degree under the

influence of Assyrian art. The oldest examples of Urartu art were unearthed at

the royal graves at Altintepe (Figure 9). In the Urartu art of jewelry making,

the techniques of casting, granulation, and embossing were used quite

effectively, and a vertical or horizontal symmetry is dominant. The figures in

this jewelry show the stylistic features of the larger plastic works. The

Urartus were also masters in working ivory, and large quantities of pieces set

with carved ivory and of animal figures were produced (Figure 10). Oval,

cylindrical, and spherical gate beads in a variety of dimensions were also

quite common. Such agates are for the most part of homogeneous colour and the

occasional exposure of the colour of the interior in fragmented pieces could

be considered proof that the Urartus aware of the technique of colouring agate

(figure 11).

Urartu tripod handled cauldrons produced with

a casting technique and worked with figures of bulls, gryphons, and human

beings were carried by trade routes as far as Italy. Embossed Urartu shields

and helmets and their harness ornaments are all works of art of superior

quality. Popular arts, which developed among the Urartus alongside the art of

the palace was more stylised and primitive, but nevertheless, its livelier

figures and compositions are evident.

Phrygia-the Country of Midas (750-300

B.C.)

The Phrygians were one group of the sea

tribes which overthrew the Hittite Empire. Around 750 B.C. they founded a

kingdom whose capital was Gordium (near modern Polatli). During the reign of

Midas, who in mythology is known as the kings who turned everything the

touched to gold and who was adorned with donkey's ears, they established their

dominion over the whole of Central and Southeastern Anatolia. The Cimmerians

who arrived from the east in 695 B.C. destroyed Gordium, whereupon according

to legend, King Middas committed suicide by drinking the blood of a bull. A

short time later, Phrygia was conquered by the Lydians (650 B.C.) and then

subsequently continued its existence under Persian rule. Despite the fact that

the Phrygians were a Balkan tribe, in a short time the became Anatolian,

creating a unique culture affected by Late Hittite and Ionian art. In addition

to such arts as woodworking, furniture making, and weaving, they were also

masters of metal casting three-legged cauldrons and fiale bowls (similar to

Ottoman bath bowls) are examples of this famous Phrygian bronze work. The

Phrygians greatest contributions to jewelry making were their fibulae made in

various sizes (Figure 12). These were nass produced using a casting technique,

and spreading along trade routes as fas as Italy the created a fashion in

their day.

In the mounds around Gordium, articles of

well worked ivory have also been found in addition to such works of bronze

(Figure 13). The rich adornments on the Mother Goddess, which appear on rather

large perfume bottle made of onyx in he shape of the Mother Goddess Cybele,

give use information about the superior jewelry making abilities of the

Phrygians.

Ionia-The Integration of East and West in

the Aegean (1050-550 B.C.)

Starting from around 1050 B.C., the Ionian

cities in Western Anatolia continued their existence as primitive agricultural

societies for about three hundred years. On the one hand affected by the

island cultures to their west, these cities (Ephesus, Miletus, Didyma,

Erythrae, etc.) after the 750's B.C. to a large degree adopted Egyptian,

Phoenician, Assyrian, and Late Hittite art as a result of their commercial

relations, and internalising it, they grew. It was these original synthesis

which gave birth to "Orientalising" in Greek art. At the same time

between 800 and 600 B.C., the important contemporary neighbours of the Ionians

in Anatolia such as the Lydians and the Phrygians were also alive, and there

was continuous cultural interplay among them. The temple of Artemis at

Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World was an important center of the

Mother Gooddes cult. The oldest (800-700 B.C.) examples of Ionian jewelry are

fibulae and rings found around Izmir. These are in the form of simple bronze

or silver rings or spirals. The fibulae are generally of Aegean island types.

Rich ivory carvings, jewelry, and small statuettes offered to the Temple of

Artemis at Ephesus in the orientalising and Early Archaic Periods (700-600

B.C.) are among the important finds of this period (Akurgal, 1951). Some of

the ivory articles appear to have been imported from various eastern sources

by traders. Ionian ivory articles, produced under the influence of these

imported wares can be distinguished from those of foreign sources by means of

the softness of their lines.

The composite creatures of Eastern mythology

such as sphinxes, sirens, and gryphons were adopted and employed in Ionian

ivory carvings (Figure 14).

Among gold jewelry one finds boat-shaped

earrings (Figure 15), uniquely Anatolian pins, fibulae (Figure 16), and

brooches. Brooches in the shape of the bee (Figure 17), an animal sacred to

Artemis, and of a sparrow hawk are interesting examples. Quartz crystals,

which are common in the area, were also worked masterfully in the manufacture

of bead jewelry (Figure 18). It should not be forgotten that some of the

neighbouring country of Lydia, where the pinnacle was reached in gold mining

and well-entrenched jewelry making. It is known that from time to time the

Ionian cities remained under the rule of Lydia.

Sardis, the Capital of Lydia and City of

Gold and Jewelry Making

There is not much known about the origins of

the Lydian's. Whose capital was Sardis (around modern Salihli). They begin to

show their presence after 700 B.C. Although their language is of Indo-European

roots, it also bears elements of older Anatolian languages. Expanding from

time to time, Lydia also took within its borders its neighbours such as

Phrygia and Ionia. Following occupation of Anatolia by the Persians in 546

B.C. the Lydians collapsed, and like all other Anatolian cities, Sardis was a

satrapy under Persian domination. This period at the same time corresponds to

the development of an artistic style known their architecture, they themselves

were to a great degree inspired by Ionian culture.

Sardis was at a point where east-west trade

routes converged. To put it more correctly, all roads passed through Sardis,

the reason being that gold collected from Mount Tmolos (Bozdag in the south by

the river Paktalos (Sart Cayi) collected in the alluvial mud of the vally.

Aware of this fact, the Sardians were masters of working and purifying gold