LANGUAGE AND REALITY

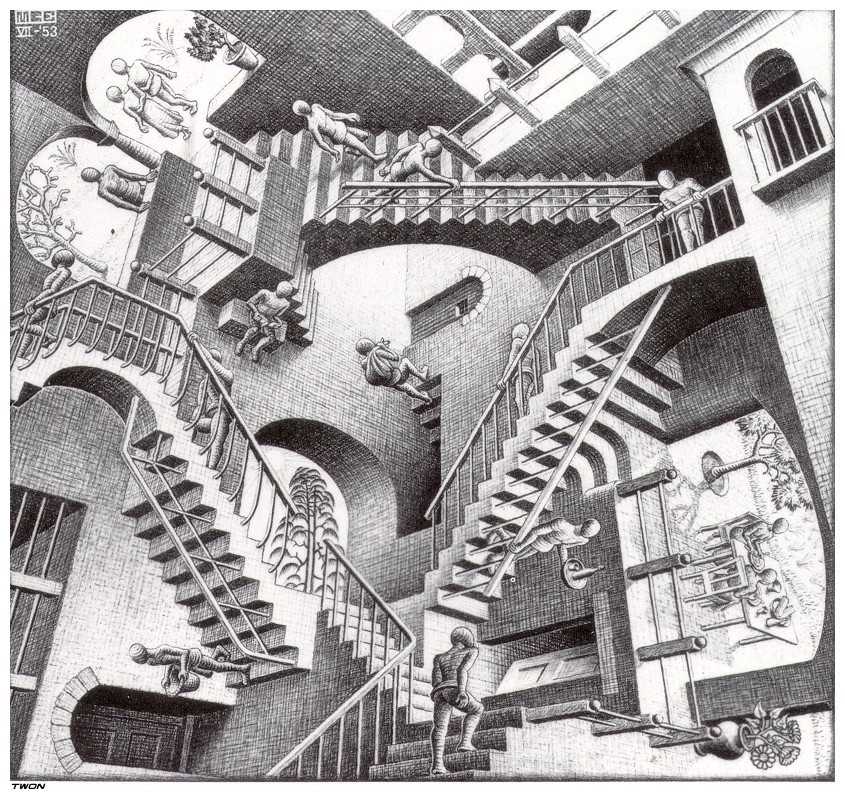

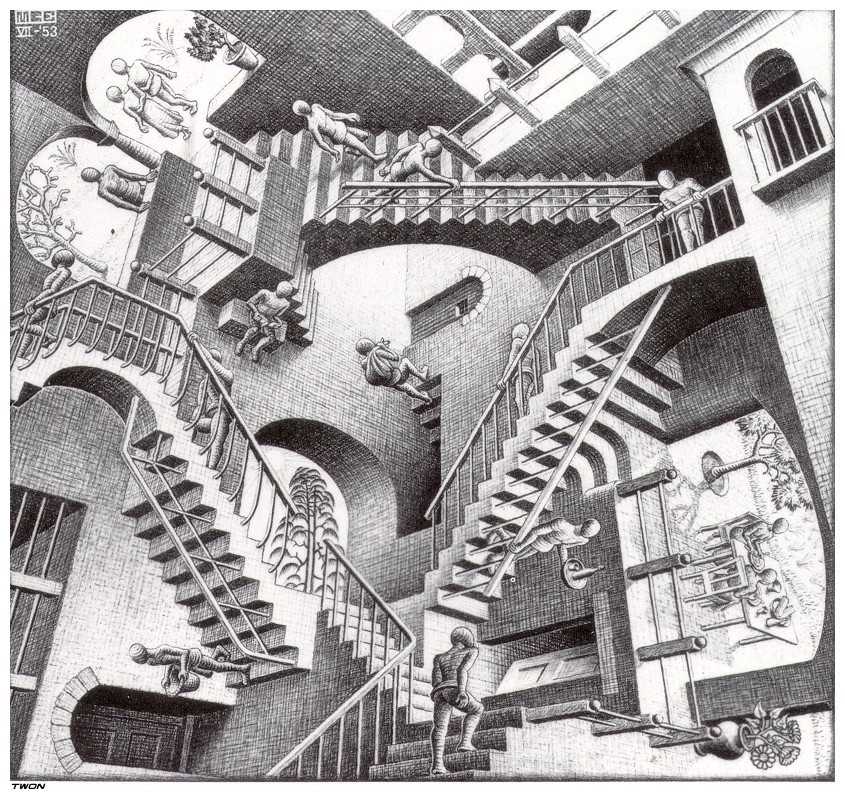

Relativity, 1953, by M.C. Escher

The world is not ready categorized by God or nature in ways that we are all forced to accept. It is constituted in one way or another as people talk it, write it, argue it. (Jonathan Potter)

I invite those who are interested in the investigation of the relationship between language and reality to read a thought-provoking and fascinating book written by Jonathan Potter, Representing Reality: Discourse, Rhetoric and Social Construction. This work tries to shed light on the controversial question: How does language construct social reality? Language, as we all know, is never transparent or neutral. Language does not confine itself to reflect or to represent the world like a mirror. We constantly use language to build up "factual descriptions" Potter claims. We continually use these descriptions to perform certain actions, or, borrowing the philosopher Austin's famous utterance , "to do things with words" . Everyday we produce successful and unsuccessful descriptions to achieve our purposes. A description is successful when it resists undermining and it is recognized as true, solid, unquestionable by our listeners. In the second part of his book Potter analyses how factual descriptions are built up in different kinds of texts: newspaper articles, counselling reports, everyday conversations, talks among documentary film makers. His method consists in identifying the strategies and devices the speakers adopt in establishing the epistemological and action orientation of their utterances. The factors involved in the epistemological orientation are: the speakers' interests, their category entitlements, their desire to get consensus, their capacity to corroborate their arguments, their ability to reproduce the factuality and objectivity of empiricist discourse, their way of expressing modality (e.g. X is a fact, I know that X, I claim that X, I believe that X, X is possible and so on). The factors involved in the action orientation include: categorization, the words used to categorize reality, in other words, the speakers' lexical choices; agency management (declaring or obscuring responsibility), ontological gerrymandering (what we choose to say and what we omit), extrematization and minimazation (the way we emphasize or smooth an event or an action). Obviously, Potter regards language as a social practice and his study focuses on discourse meant as "language in action".

Now, I would like to draw your attention on the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Unlike Potter, whose approach is openly "anti-cognitivist", (he does not take into account the schemata or mental representations stored in the human mind but focuses on the social dimension of language), Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf argue that it is our way of thinking that determines our language uses. Writing in 1929, Sapir argued in a classic passage that:

Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society. It is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection. The fact of the matter is that the 'real world' is to a large extent unconsciously built upon the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached... We see and hear and otherwise experience very largely as we do because the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation (In E. Sapir, 1958, Culture, Language and Personality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

A few years later, his student Whorf maintained that:

The background linguistic system of each language is not merely a reproducing instrument voicing ideas but rather is itself the shaper of ideas, the program and guide for the individual's mental activity. [...] We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. [...] The world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds. We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way - an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language.

The hypothesis of linguistic determinism involves serious consequences. If our language is determined by our thought, does this mean that we are imprisoned or trapped in it? If we learn another language, are we also capable of assimilating a new way of thinking? But, in the last analysis, can we learn another language? Is it possible to translate from one language into another? Is cross-cultural communication a mere utopia?