| THE MISSION OF MONGLIN | |

| THE MISSION OF MONGPING | |

| RETURN TO ITALY | |

| THE DEATH OF FATHER VISMARA | |

| FATHER CLEMENTE’S LAST LETTERS |

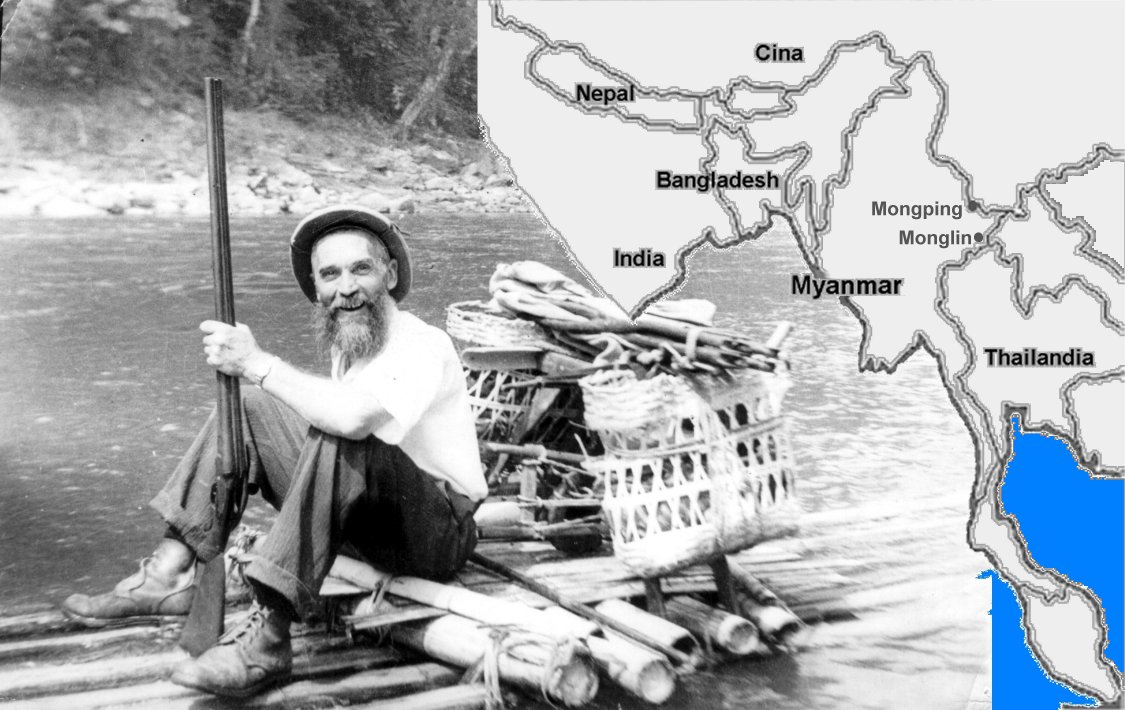

The mission to which Father Clemente Vismara was sent, Burma, is now Myanmar, a

land of adventure then wrapped in mystery.

Leaving from Venice on

August 2nd 1923, he arrived in Rangoon (now Yangon) on September 9th but he

had not yet arrived at his mission, Monglin, which he reached in October 1924.

He stopped in Toungoo for five months to learn English and a little of the

'local languages, then with his traveling companions, Father Luigi Sironi

and Father Erminio Bonetta, founder of the mission of Kengtung, he left for

Taunggyi, the extreme outpost of English colonisation. The region destined

to Father Vismara was beyond the Salween River and was under the authority of

“Sabwa”, a native king who came from the dominant race in the region, the

Shan.

The mission of eastern Burma had been entrusted by the Holy See

to the Missionaries of the Lombard Seminary (now PIME, the Pontifical Institute

for Foreign Missions) in 1867, but started only in 1911, whereas the

Apostolic Prefecture of Kengtung was established by Pope Pius XI as late as

April 27th, 1927.

To the Superior of the Lombard Seminary, Father Paolo Manna, he wrote: “I

am delighted to have been destined to Burma, because they say it is the most

apostolic among missions and it was my ardent desire to go to a place of

sacrifice and hard work /. .. / I am going to my mission with a right and true

intention to do good for the glory of God (and mine too, but in Paradise). I

would love my sacrifice to be complete, absolute and obscure, and trust I will

be able to do this with the help of God”.

Endowed with an

exceptional adaptability and a good dose of that “Ambrosian good humour”,

originating from a serene soul, even the hardships of missionary life, as

Father Clemente describes them in his early letters to The Catholic

Missions, journal of his Institute, acquire the flavour and charm of adventure

and conquered to missionary life, the enthusiasm of many vocations. So we can

say that there was no inconvenience to which Father Clement could not find ways

to adapt himself or face, with the good humour deriving from of his calm and

confident nature, but above all from the conviction that he was doing everything

for God.

Finally in October 1924, Father Clemente reached Monglin,

after a six days’ journey on horseback from Kengtung and having forded 28

rivers and streams. He also had to cross the Salween river, the mythical

border of the mission.

This is how Father Clemente described that

moment in an article in “The Catholic Missions” of his Institute:

“How many years of hard work, aspirations and trepidation found their conclusion

in that river, never known before and yet so often dreamed and desired! How

many hopes of sacrifice, immolation, and dedication for the good of unknown but

dearly loved brothers, did that river open! All our past life came to our

minds, as a light burden and we saw the great and beautiful future ahead of us,

but we also felt as though we had expected and dared too much, and we were

invaded by a shudder before the sacrifice ahead of us. But it was only a

moment...

... Faith in God who sent us made us continue with the hope and joy of

offering ourselves to the holy work of spreading that faith which leads and

guides us on the divine wings of the Spirit. We are the priests, the young

priests, the successors of the fishermen of Galilee. Our battle is their battle,

our weapon is the same weapon they had, the Crucifix, but is our virtue the same

as theirs? How much emptiness before this question! How much need of virtue, and

of prayers!

O you who love the missions, pray, pray for us, as prayers

are powerful and holy. Our work will be your work. He who is the Father of all

in seeing us all united in the same effort: “Hallowed be thy name, thy

kingdom come;” cannot but bless our work as it is His work and grant us, one

day, the crown granted only to those who have legitimately fought our

battles".

In this spirit, Clemente began his mission in Monglin, a

remote village in the mountains of Shan State.

The most accurate description of Monglin is provided by the same Servant of

God:

“I think no one of you readers knows where Monglin is. But this

is not due to ignorance, because I too, to know where this blessed country was,

had to come and live here.

Monglin a hundred years ago did not exist,

but shortly we will celebrate its centennial. It is not a big town, but a series

of many small villages, one after the other on either side of the road for

about six miles.

The elderly say that the place where all these villages

now stand, was inhabited by wild elephants.

Monglin means “borderland” and

is located on approximately 21 degrees north latitude and 100 degrees east of

Greenwich. We are in Indochina. The Mekong River is 8 miles to the south-east.

Kengtung, the capital of this state, is 125 km from here and almost as many

from the northern border of Thailand. Sixteen miles to the west lies

Laos.

How many are the residents of these small villages, I do not know,

because here there are no records of births. I think it would be exaggerated

to calculate two thousand inhabitants”.

The first home of Father Vismara was a large room divided into five

rooms:

“A room serves as chapel during the day and a dormitory at

night, another room for us and a third is used as pharmacy, dining and

conversation room, etc.. , the middle one is the kitchen, and a small room for

the catechist.

The clay floor is a bit uneven. There is no furniture, not

even a chair. The cases we brought with us serve as : chairs, table and

dresser ... and all around is thick bush very difficult to

penetrate”.

There was also great abundance of mosquitoes, rats,

lice and ... other domestic animals, from which the missioners, Father

Vismara and Father Bonetta who stayed for some time with him, defended

themselves smoking local tobacco in their pipes, so that “entering the house

at night, it is like entering a cave in the slum of Rome in the days of

Quo Vadis”, Clemente wrote in one of his early letters.

Gradually Father Clemente became aware of the new world in which he lived: the

scourge of opium smoking, poverty, pagan beliefs still deeply rooted and

leading to a certain fatalism that did not stimulate people to engage in work

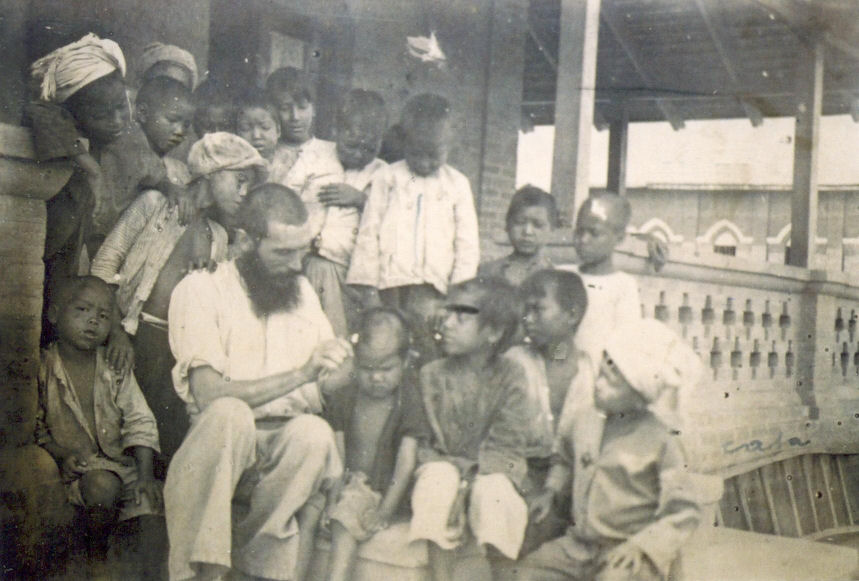

and achievement. Since the early months of the mission, Clemente discovered

what was the main target of his ministry: children and young people whom

he considered the future of that people, both as Christians and as

nation.

Despite the extreme poverty that Father Vismara had to face, he

soon began to receive the first orphans. Nine are the children who formed

the first small group of hundreds that Father Clemente would have

collected, raised and educated and many of them became priests, nuns and

catechists.

Extreme poverty was not the only virtue that Father Clemente

had to exercise: harder to achieve was the patience to wait for the fruits

that did not seem to mature and the duty to accept the eastern

philosophical calm, as the dynamic Father Vismara, like any good Lombard,

wanted his job done well and quickly,

“We are here to live the life of

the poor of Christ, but we feel the happiness and joy of Heaven, the

cares about tomorrow are relatively light, since the work is not ours, it is

the Lord’s. /.../ We leave to posterity a Monglin better equipped with

Christians and with the necessary, we keep the first sowing for

ourselves”.br>

It is practically impossible to describe what the

Servant of God did in the years of mission in Monglin. He built churches

in various districts, health clinics, hospitals, small schools, converted

and baptised hundreds of Christians.

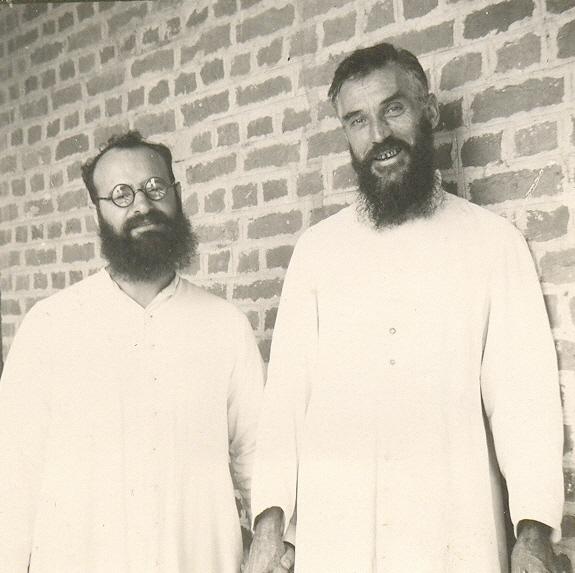

He had at his side several brothers to help in his mission, but Father Vismara

was almost always on his own because due to the poverty and hardship of those

years, many died soon, so that even he feared for his life and prepared his own

coffin:

“I care about my skin, so I want it to be put away

properly”,

but he certainly did not foresee that the coffin he had

so carefully prepared, would have had to be given away and redone eighteen

times!

In Monglin he built the church first and his own house only in

1929; then the orphanage, which still houses many poor children and orphans,

and a convent for the sisters who arrived in Monglin in 1931.

He

founded new missionary districts and explored villages never seen by a foreigner

before. In these visits, the activity that occupied him most was to gather

children and young people. The natural suspicion of the people was defeated by

his attitude towards the poor, the sick and by his prayers.

In Monglin orphanage, the children soon became hundreds: abandoned boys and

girls, either because they were orphans or had been sold by their parents to

buy opium.

Father Clemente welcomed them all, whatever their race or

religion, without calculating whether the room or the food he had were

enough.

In order to keep them, he invented a thousand different trades

and taught them to grow rice, raise chickens and hogs, to hunt in the

forest, to grow vegetables and flowers that were sold at the weekly market in

Kengtung.

Intelligence and common sense helped him to be sure, but above

all Clemente had a great trust in Providence. Even when he lacked everything

he used to say: “The Lord Provides” and, as witnessed by many Burmese,

nuns and laity, Providence always came to the rescue.

Father Clemente stayed in Monglin until 1955, for over thirty years without

returning to Italy.

He did much, very much indeed, and the secret of his

success was the novelty that he carried in him, the enthusiasm that made

him young even at ninety , the desire never to be tired of working for God, of

renewing himself in children, lepers and the sick.

In 1955, his mission was

prospering and had many conversions among the Buddhists with whom he had

excellent relations of dialogue and mutual respect based on the value of

man.

His love for all was the most effective mean of teaching and

witnessing his faith. Father Vismara was always smiling, so that he is

remembered by his people as “the priest who was always laughing and joking”,

but as the Burmese witnesses say, he had a way of teaching even with his

jokes.

In 1955, after 32 years of intense and fruitful work in Monglin, where

Father Clemente was considered the father of all, came the request for him to

move to another mission.

“My dear, my heart wavers! – he wrote

to his friend Pietro Migone recalling his move - after 32 years, when I

least expected it, I was moved from Monglin to Mongping (225 km away). I obeyed

because I was absolutely persuaded that if I did something of my own will I

would have done wrong and would not be successful”.

When the Bishop

Monsignor Guercilena told Father Clemente: “You will have to move from

Monglin to Mongping”.

“All right – Clemente said – do you want me

to come away with you or are you going to give me a few days’ time to say

goodbye to everyone? /.../ I will be happy wherever you send me. Just let me

go to church to digest this unexpected blow before the Lord”.In this

circumstance too, Father Clement showed his obedience, promptness and great

fortitude.

At 58, he started another adventure Mongping.

Father Vismara’s new destination was not like the one he had left in

Monglin:

“In Monglin I had built half a city, a school of nearly

one hundred orphans, boys and girls etc.. etc.. In addition I managed (or,

rather, the Lord did) to take into our flock some Buddhists who are quite

influential in this area.

Rather than my Christians (and they were all

mine), I was sorry to leave the pagans, both of the plains and of the

mountains.

We knew each other so well that whether Catholic or pagan, I was

granted the same reception in every village and I had such high hopes.

Now

I find myself in Mongping: a cold shower for many reasons: the main one is

that too many here smoke opium; for two years the missioner’s house and

the village were occupied by soldiers who left heavy signs of their

presence.

The convent, which was large and flourishing, is now down to

twelve tiny little girls.

The buildings all need to be repaired, only the

house is in bricks, the wooden church is now forty years old, and an

orphanage is most necessary. At the moment it is just a pile of bamboo and

straw.

I brought with me some people from Monglin to help me, but they soon

ran back there, and ,in my heart, I could not blame them”.

Everything in Mongping had the flavour of desolation and abandon. However,

after only a few months, the Servant of God had visited almost every

village of the mission, but the situation was difficult everywhere; the

separatist guerrillas, followed by independence in 1948, aggravated the

situation of poverty and precariousness.

The second part of the

missionary life of the Servant of God was marked by the presence of guerrillas

and bandits:

“I'm here in Mongping and I feel as though I had fallen into

the second underground floor of the Mamertino prison – he wrote to the

General Superior of PIME, Father Luigi Risso on May 15th 1955 – Will I

make it? In terms of materials, especially food, I am worse off, and you can’t

find goods. Father Gerosa (his predecessor, Ed) lived like the natives, so I

had to buy plates, glasses, chairs and finally the table saw a tablecloth. I

redid the whole floor of the house with cement. The house roof is leaking. I

replaced the church windows. I painted the whole house and I even put in a

pendulum clock. /.../

I still have two villages to visit, then I will have visited all my

people. In no chapel did I find a chair, a table or even the crudest kind of

comforts, but worst of all, they sell opium”.

That of opium smoking

was a widespread scourge of that mission and seemed unstoppable; it caused

a moral and material misery that brought families to ruin, and to rid

themselves of their children.

Father Clemente, in Mongping, started all

anew and after four years he wrote: “... I left my unforgettable Monglin with

everything: home, church, convent, hospital, two orphanages, etc.. etc.. and

I came here with only my clothes, what's more I found almost nothing, there

is only one passable house in bricks. The first year was very hard indeed and

it took me some time to get back in the saddle. Now I am back on it, but

unfortunately I am sixty-five; if I were as handsome as ever, I would not

care about it”.

Father Vismara did not quail, he started to do what

he had done in Monglin: he collected orphans and educated them, he built

the church, a school, an orphanage, and continued to visit all the small

villages, scattered in the mountains. All this in an increasingly difficult

situation. In fact, from 1950 onward, the government began an open

hostility towards the missioners: 5 missioners of P.I.M.E. were killed in

six years. This meant, for Father Vismara and his brother missioners, living

with the prospect of a possible martyrdom.

Father Vismara knew how

to be cautious and, in 1960, he left the mission and hid not to endanger the

lives of his Christians: “I will be unavailable for I don’t know how many

days, nor do I know where I will go and how to get there, because there are

rebels everywhere even in my village. But, as I consider myself unworthy of

martyrdom, I will try to sneack off, as I already managed to do twice, even

under the bullets”.

This does not mean that he was not ready to give his life, but Father Vismara

had his feet well planted on the ground: until it was possible it was better to

remain alive, not for his own good, but for the good of the people. The

missioners were few, too few and survival was above all a duty to the people.

One of his brother missioners, Father Badiali Rizieri, said that, while the

others were prostrared and discouraged by the many losses, Clemente used to

say: “We have to survive to do what they cannot do anymore”. He

- Father Badiali continued – had this basic courage, full of faith and love of

life. A life to be lived with joy, as it is given us by the Lord. And then he

had a great desire to save from death as many lives as he could, particularly

the children. Save many lives, save many children.

Besides the killing

of the missioners, no less painful was the killing of catechists,

perpetrated to eliminate the Catholic faith and invite people to return to

ancient beliefs. Father Vismara did his best to save them and also to understand

the reasons for the defection of some: “All the catechists have taken

refuge here. I'm sorry, because, with the fear they have in them and no one to

defend them and give them courage, they are not to blame if they return to

paganism, if only temporarily. I do not know what to do. Let’s hope for

better days”.

Those were hard years for Father Vismara, but his

faith and hope sustained him in every situation.

Father Rizieri

still remembers the short time spent with father Vismara in Myanmar: “We

prayed together in the sense that we were in church to pray as did the priests

of the past. Father Vismara prayed and prayed ofter. He said: “How could I be

cheerful all the time without prayers? How could I accept the arduous labours of

some hard days?”. He prayed constantly with great devotion and intensity,

even when we were in pagan villages. The Word of God was a great support to

us, it was our constant reference and food, because it pointed our way every

day, because the Gospel is the missioner’s manual. Father Vismara especially

loved the figures of Abraham and Moses leading His people out of Egypt. It

gave him the strength to be patient with the people: he used to say that if

God had been so patient, so he had to be with his people”.

Determined not to return to Italy, after 34 years of mission his brother

missioners prepared his return and Father Vismara, although reluctantly,

finally accepted.

He arrived in Italy in February 1957, welcomed as a friend

by everyone, even those who had never seen or known him, because his letters

and writings (he always kept in touch with relatives and the many benefactors)

had preceded him, and made people know and love him.

Father Clemente

met his brother Franco, the last of his siblings still alive and several

nieces and nephews. He arrived in Agrate greeted by the sound of the church

bells and by the local band; the religious and civil authorities and all the

people living in Agrate, welcomed their missioner with great joy.

He was

no longer young, but sure-footed and with a proud carriage; the look in his

eyes was made austere by his long beard, however his shining eyes were

clear and sweet, but just as piercing.

The image that the people of Agrate

preserved of this meeting is that of a man proud of his choice and happy to

do good.

His presence in Agrate, although intermittent (he spent his

stay in Italy in many meetings of missionary animation in seminars and in

various parishes, arousing enthusiasm and interest) strengthened a bond of

friendship that in 34 years had never slackened and was prepared to live

just as many more, overcoming barriers of time and distance, involving old and

new generations.

Clemente took advantage of his holiday to see his old

friends, but he felt also an urgent need to restore his spirit and decided to

spend a month at the home of spirituality “Villa Mater Dei” in Masnago (Varese)

for the month of Ignatian spiritual exercises, despite the protests of

friends and relatives to whom a month seemed too long, considering the

fact that he had returned home after thirty-four years and that most probably

he would never return.

Father Clemente, almost at the end of his Italian sojourn, during the month of

September went on a pilgrimage to Lourdes, as he was particularly devoted to

Our Lady of Lourdes. In his villages of Monglin and Mongping there is a

grotto built by him with the help of his people.

The day of his

departure was approaching. Italy, after all, was becoming a little tight for

him and after eleven months of intense holiday he greeted the people of

Agrate saying, “Take a good look at me: we won’t see each other

again”.

To a reporter from the newspaper Italia who asked

him about the missionary life, he replied: “Redemption is a slow, hard and

penetrating work, it must take possession of our hearts. All the means we have

are accidental..., only Jesus can redeem, the missioners are simply co

-operators. He carried the cross, we can do nothing else but act as he acted.

I am sixty and I have been holding a return ticket in my pocket for a long

time now. /.../ I am returning to my mission for a necessity of my own and for

my sense of duty I can not stay here. There are so many people scattered in

isolated villages without roads, in forests; they need a priest, we can not

abandon them”.

Clemente left Italy on 24th December 1957, happy

despite having only a one way ticket in his pocket...

Father Vismara

resumed his place in Mongping, restored in body and enriched by the encounter

with an evolving reality such as that of Italy in the fifties, very

different from what Clemente had left in 1923. The Italian interlude was

closed for ever, but it remains a fact that it attracted new friends and

benefactors into the orbit of the missions.

The sixties were difficult

years for Burma. With the coup of General Ne Win of March 2nd, 1962 began the

so called “Burmese way to socialism” which was an irreversible turning

point for the country, leading to economic and political decline.

In 1965 a new concern appeared on the horizon: the government was expelling

all the missioners who had come Burma after 1948, the year of independence,

confiscating their buildings: schools, hospitals,etc ... They were difficult

times for every day news came of new expulsions. Even Father Vismara, although

he had come to Burma before 1948, was told to be ready to leave. But he did

not lose his calm; he certainly knew that he would work until the last

minute.

“It would be dreadful – he wrote to his friend Father

Pedro Bertocchi – to be forced to abandon my flock after 42

years”.

“I can’t be persuaded and despite everything I have the

illusion I will stay until the end. My school is still mine, and we keep on as

usual. /.../ Of course I'm sorry but what pains me the most are the orphans

and children who are a great many. They can not even study anymore because

there are more taxes to pay and they have nobody. /.../ They would go back

into the woods to catch birds and fish”.

In 1966 the government decreed the expulsion of all foreign missioners and

prohibited the entry of new priests.

For Father Clemente to remain in

his mission meant to give up his chances of returning to Italy. A witness

for the Cause of Canonisation so remembers that time and the decision of Father

Vismara:

“When the government expelled all foreigners from Burma, a

fellow missioner urged Father Vismara to return to Italy with him. Father

Vismara said he would decide after celebrating the Holy Mass, to listen to the

Lord, to Whom he would have applied to enlighten him on what to do. He decided

to stay, as he had always thought, because he wanted to die near his people. He

stated that he would stay with us forever, until his death and that he would

never return to Italy because he had come here for the love of God”.

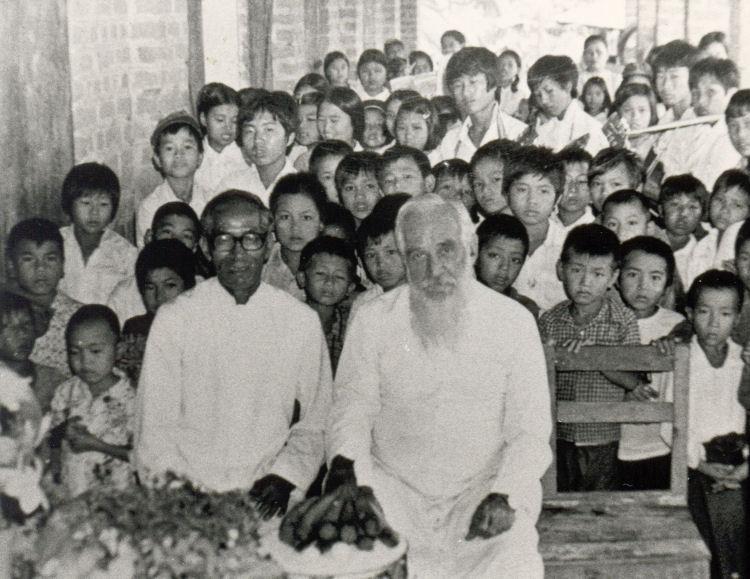

Years went by and although Clemente was no longer “young and handsome, with

eyes the colour of the sea” as he said when he left Italy in 1923, he

tirelessly continued his missionary work. It is impossible to describe all his

accomplishments, how many villages he visited, how many children he welcomed,

fed and educated, but we can make a record of the permanent works that are

still a reference point for the villages of Monglin and Mongping: orphanages,

churches schools, home for the missioners, Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes,

several chapels in the villages and brick churches, all this until the end of

his life.

With these constructions Father Clemente assured employment

to many families. He taught them to do masonry, farming, etc... And this

was an important aspect of his mission: promoting human development,

especially in young people so that they would overcome the natural fatalism

that led them to accept poverty as a normal condition and to ask without

committing themselves.

Father Vismara found and educated hundreds, thousands of orphans in the 65

years of his missionary life, but his whole work of education had this goal:

promoting the development of the person so as to acquire

dignity.

Accustoming his people to work was a form of education that

looked to the future. Father Vismara was a man of boundless charity, but he

also educated his people to the sense of the importance of work and worked with

them for this.

“If you accept to become a missioner - Father

Clement wrote - you must accept it unconditionally, otherwise you would be

a mercenary. Preaching is not enough; holy celebrations are not enough;

baptising pagans is not enough. The one and only way to achieve one's

ideal is “lose yourself to save the lives of those lost.” The missioner, if he

wants to live, and make others live has to adapt to all jobs both noble and

less noble ones: scholar, peasant, poet, cobbler, aristocrat, commoner ...

and the litany goes on. /.../ Our main goal is not money, but to educate people

to work in order to win the honour of earning their own food”.

Welcoming the poor, of whatever religion they were, was one of the principles

which Father Clement never failed to apply. His faith enabled him to see God

in all creation, especially in poor and abandoned people. He used to repeat to

the Sisters of Maria Bambina , who took care of the orphan girls,: “Do not

worry. Providence will not fail”. Even in his last days before his death,

he urged them not to refuse anyone saying that he would provide for his

children from Heaven.

His house was never closed for anyone, even for

the soldiers, camped near the mission, disliked by the population, but who

always respected Father Vismara.

Many conversions from paganism arose

mainly from the charity that the Servant of God lived without

distinction.

The consistency between word and life, gave credibility to

what he taught, as he used to face life simply day by day, without

speculation.

Father Clemente never became old, his was a youth that was

renewed in ever new giving of himself.

At the age of 76, on the

occasion of his sacerdotal jubilee he wrote: “I'm not old, I think I

have been through three successive youths. Aurora: youth made of dreams,

careless, restless and even irresponsible, the noon: youth as a priest,

active, laborious, arduous, but satisfactory, and the sunset: youth calm and

slow, less noisy, but more efficient, experienced, perhaps more human...

Life can not flourish if it remains locked within its narrow limits; it

renews and multiplies offering it. I believed in love and have loved without

expecting to be loved. I do not know what disillusionment and melancholy

are”.

Father Clemente’s long life reached its end on June 15th,

1988.

Monsignor Than, former bishop of Kengtung from 1969 to 2002,

recalls this first meeting with Father Vismara: “I met Father Clemente for

the first time in 1957 in Yangon. Father Vismara was returning from Italy

and I was leaving for Rome. It was a fleeting encounter. Then as the Lord

ordained, we met again many years later, on June 5th, 1969, and we stayed

together in the diocese of Kengtung for 19 years and 10 days, until June 15th,

1988, the day of his death.

In all those years we spoke, travelled, and

discussed many things, particularly about his orphans, whom he entrusted to

my care after his death. Because orphans are our future

hope:

“At least some of them will become priests and take our

place. Some will become nuns, and some will become good catechists and the

rest of them, good Catholics”,

our Father Vismara used to

say. From him I had very good and edifying examples both for my spiritual

and pastoral life.

Father Clemente Vismara was above all a man of faith.

He saw

things and every day life through the eyes of faith. His faith enabled him to

see God in all creation, especially in poor and abandoned people.

He

used to say: “As God created me, He created the poor, as He loves me, He

loves the poor, as he lives in me, He lives in the poor. We are all His

beloved children. So if I love the poor, I love God. If I do not love the poor,

I do not love God”.

Father Clement was a man of hope.

His strong hope and trust in

God and His Divine Providence, made him accept a large number, as large as

possible, of orphans in his orphanage.

He used to say: “For the poor

orphans I will do my best, and God will do the rest. With my work in the

garden and with my tongue in my mouth and with my own two hands, I will be

able, with God's help and his blessing, to take care of many orphans who are His

children. I take care, feed and educate His children and God certainly, without

fail, will help me. No problem. It does not matter if no one helps me to feed so

many orphans because Divine Providence will help me. I trust in Him and I'm

sure He will never leave me alone. More than that, I have every hope and

complete confidence that one day He will take us to His eternal home in Heaven

after our death. I and my poor orphans live together here on earth and

then we will be together again in Heaven. What happiness, what joy! My only

trust and hope is in God and His Divine Providence”.

Father Clemente Vismara was a man of charity.

The love of Father

Clemente was sublime. His love for others, especially for the poor orphans,

speaks for itself. He loved God with all his heart and his soul, with all his

mind and he loved his neighbour as himself for love of God, This was his

second life.

He was also extremely good and caring towards his fellow

priests, especially the poorest. He always shared with them the little money he

received from his generous friends and benefactors.

Father Clemente was a man of poverty.

Although he could be

considered a rich priest in the mission field with the money and other aids

received from his loved ones in Italy and other good and generous benefactors

all over the world, he did not want to be so. But he would rather share the

money and other things with his poor and abandoned people. He often shared

his food with his sick orphans.

He used to say: “Christ became

poor to make us rich ... He emptied himself to fill us. I also have to drain

myself to give my poor orphans sufficient daily food”.

When

Father Vismara died on June 15th, 1988, he only had 1500 kiats, more or less

equivalent to US$ 15, but many were the orphans bequeathed to his

successor.

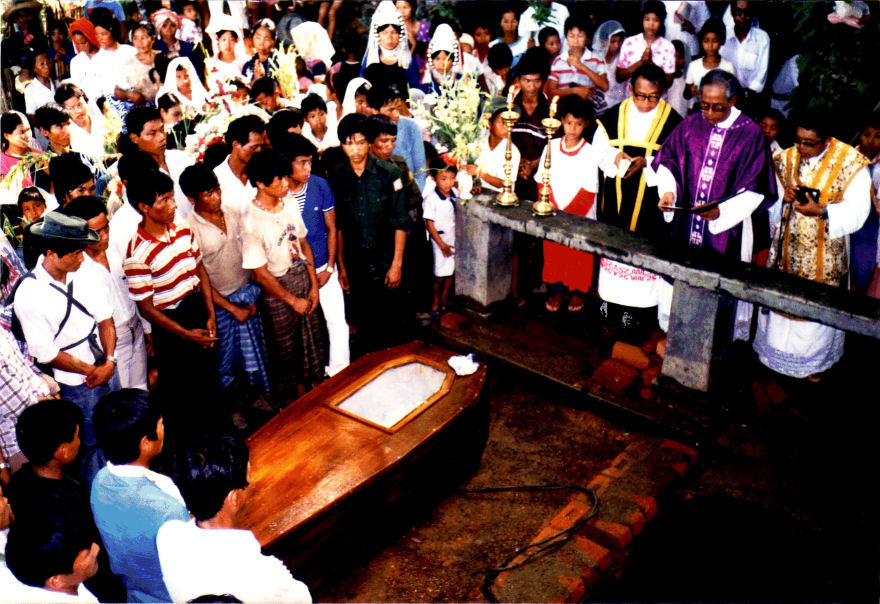

From 1st to 6th of June, 1988 Father Vismara was in Kengtung

and on June 7th, feeling unwell, he desired to go to Mongping because he said

he wanted to die among his orphans.

This is how Monsignor Than remembers the last moments of Father Clemente’s life:

“On my return from a village I was told that Father Clemente was ill, it was

June 15th , and I hurried to Mongping. I left at 11.00 a.m. and arrived by

Father Clement at 6.15 p.m., but he could not tell me anything. I remained with

him for two hours doing everything I had to do for him, praying, giving the last

rites and so on. Father Clemente closed his eyes for ever, in great peace, at

8.15 p.m. A great sorrow for us all!

According to the desire of his

Christians, his body was kept in a classroom for 6 days, giving the

opportunity to all Christians and his Buddhist and pagan friends to come and

pray and give their last respects to their Father for the last time. His

orphans were around him.

I was surprised to hear my priests, nuns,

catechists and faithful ask for his old and used clothes as a relic of Father

Clemente Vismara. This struck me and made me realise that they and the

children acknowledged him as a holy man, a saint in advance.

I am

happy to reiterate that the entire people of the diocese of Kengtung fully

support the Cause of Canonisation of Father Clemente Vismara.

I thank

you immensely for all you do for him and for the orphans of our dear,

unforgettable Father Clemente Vismara, your fellow-townsman

missioner.

We pray to have him declared Blessed and Holy Father

Clemente Vismara as soon as possible”.

Bishop Than Abraham, Bishop

Emeritus of Kengtung

Mongping, 20th December 1987

I am looking at your lovely faces. You

all have black hair, mine is all white. Your faces are all white, mine is

black. And yet, we are all beautiful because we are all from Agrate Brianza

and both you and I have a warm and red heart. This means that we all want the

whole world to know and love our Good God, the true and only

God.

This year I have built another wooden church. All my churches,

but 5, are made of bamboo and straw. All mountaineers have been ordered

to leave their dwellings and come to the plain to build new villages along

the main road. They say that, when there will be peace again, they will be

allowed to return there. What will become of the rice fields up in the

mountains? It is a problem without solution.

We have no bread here, we

only eat rice. Lucky you who cane eat rice soup without the toil of growing it!

O but all this will end one day!

In the picture you sent me there are 22

young men. Here I am the only one of my species and gender, but I have over 200

orphans living and eating with me.

I wish you all the best and hope to

see you in Heaven.

With love

Father Clemente

Mongping, 10th April 1988

Most Reverend Father,

Although I

have been away for 65 years, I cannot forget my nest!

I feel that my end

is approaching: it’s a year now since I lost the sight of one eye, but I am

still very handsome. I was born in the last century on 6th September and I was

baptised ( if I remember well) by Father Umberto who has long gone to

Heaven. I also fought in World War I, in the 80th Infantry Regiment and

was appointed Cavaliere di Vittorio Veneto , for which I receive every year

150 thousand liras.

What more do you want from one from Brianza like

me?

Of my gender and species I'm here all alone, I have so many

orphans, boys and girls, infants, 22 widows and forty villages up in the

mountains. They can all make the Sign of the Cross. Just think that the nun

cooks every day two and a half sacks of rice for them. They all eat but no one

earns any money.

We have four priests named Clemente: me from Agrate,

the other three belong to the Aka tribe. Here with me I have Sister

Clementina from Kengtung, Sister Josephine, etc..

I'm not completely

well. My first house was of mud and straw. I had three horses under the porch,

one for riding and two for carrying goods and equipment. And I travelled;

travelled throughout this area as a doctor, distributing Quinine, giving

injections, etc.. This is a place of malaria.

People did not know who

I was, I did not know who they were. But with time, we ended up knowing and even

loving each other.

Here the life span is too short, no one believes

that I am 91. Many missioners passed away too early at 27 - 29 - 30 - 33 - 40

and so on. The oldest is 65 years old. Foreign missioners are no longer allowed

to enter and live in Burma. But now the native priests are 12 and they are very

good, better than us.

Many greetings and good wishes.

Father Clemente