EXCELLENT

ELISA FIORENZA – English II, LM, a.a. 2008/2009 - Task 1°B

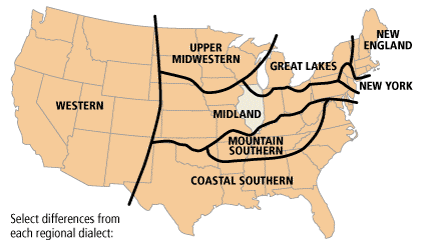

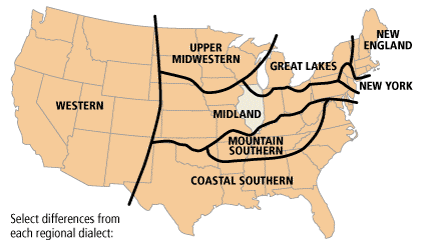

West Coast General American (henceforth, WcGA) is a regional dialect of General American (henceforth, GA) spoken in some western American countries states like Washington, Oregon and Idaho, as shown in the map1 below:

It shares many features of GA, and actually it shows important differences in opposition to other varieties of English, as for example Southeast British English. In the following analysis I will consider the main characteristics of WcGA with regard to the phonemic, morphemic, lexemic, syntactic, textual and (normative) pragmatic level.

Phonology

The pronunciation of WcGA is close to that of GA, therefore it has both innovative and archaic elements in opposition to BrE. It shows a rhotic accent, which is a significant marker in differentiating English varieties, and it is also considered by some linguistics as the least accented

form of English. A rhotic accent2 is one where r can be heard in all the places where it is found in the spelling, as in car and park.

As regards the vowels in words such as Mary, marry, merry, they are merged to the open-mid front unrounded vowel [ɛ]. Moreover, the sound /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a].

In the so-called “cot-caught merger”, the words cot and caught are homophones, since there is no distinction between the open-mid back rounded vowel [ɔ] and open back unrounded vowel [ɑ]. Other typical mergers are that of /ɑ/ and /ɒ/, which makes father and brother rhyme, and also the “pin-pen merger”, by which [ɛ] is raised to [ɪ] before nasal consonants, making pairs like pen/pin homophonous. This last merger originated in Southern American English but is now found in parts of the Midwest and West.

The flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to alveolar tap [ɾ] before unstressed vowels (as in butter, party), syllabic /l/ (bottle), and at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel (what else, whatever) is an innovation of GA, as well as the tendency to nasalize the vowels, mainly in the presence of /n/.

The phenomenon called “Canadian raising” characterizes some speakers (mainly in the rural areas, and in older speakers of Northern Washington) who have the tendency to slightly raise /ai/ and /aw/ before voiceless consonants, so that /aɪ/ (the vowel of "eye") becomes [ʌi]; [ɛ] and sometimes [æ] as [eɪ] before /g/: "leg" and "lag" pronounced [eɪg].

As regards intonation3, GA is very different from BrE: the overweight of the stressed over the unstressed syllable is a lot smaller in GA. Moreover, GA uses a "secondary stress" that can affect the position of the primary stress, too. Some examples:

advertisement: (GA) [![]() ]

/ (BrE) [

]

/ (BrE) [![]() ]

]

ceremony:

(GA) [![]() ]

/ (BrE) [

]

/ (BrE) [![]() ]

]

dictonary: (GA) [![]() ]

/ (BrE) [

]

/ (BrE) [![]() ]

]

GOOD POINT, Not usually mentioned.

Morphology

WcGA follows the typical GA tendency to use nouns as verbs, for instance interview, vacuum, lobby, room, pressure, torch, exit, gun.

Compounds coined in the U.S. are for example teenager, brainstorm, hitchhike, frontman; non-profit, free-for-all, ready-to-wear; happy hour, road trip; (verb plus preposition) add-on, stopover, lineup, shakedown, figure out, check in and check out.

Also particularly productive are noun endings such as -ee (retiree), -ery (bakery), -ster (gangster) and -cian (beautician); some verbs ending in –ize are uf U.S. origin, as accessorize, itemize, editorialize, customize.

Some words were formed by alteration of existing words, like phony, buddy, sundae; terms like motel or televangelist are American blends.

Instead of want

to and

going

to,

WcGA/GA frequently use wanna

and gonna

in speech, as in “What we gonna do now?”4,

“I

wanna

go home.”5

Gotta

(BrE:have got to) is used in a similar way to gonna

and wanna,

or as informal alternatives to

have to

or must,

as in “I gotta go now”.

ACTUALLY,

THIS IS THE TRANSCRIPTION OF A PHONOLOGICAL PHENOMENON; IT IS NOT A

MORPHOLOGICAL PHENOMENON AS IS, FOR EX., HAVE GOTTEN VS. HAVE GOT.

Some spelling variations (GA/BrE) are color/colour, advisor/adviser, program/programme, center/ centre, encyclopedia/ encyclopaedia.6

WcGA/GA has have a tendency to drop inflectional suffixes, thus favoring clipped forms, as in cookbook (vs. cookery book); dollhouse (vs. doll's house).

GOOD POINT, Not freqeuently metntioned

3. Lexicon

There are many lexical differences between WcGA/GA and BrE.

First of all, because, after the colonization, language had to evolve to describe new things (different landscapes, animals, food, clothes), qualities, ideas; then also because America has soon become a melting pot of different nationalities and cultures. For these reasons, many words were borrowed from the Indians (totem), Spanish (canyon, tequila), Dutch (cookie, boss), German (hamburger), Africans (jazz, voodoo) and other languages.

If we consider WcGA/GA in opposition to BrE, many interesting examples can be found: apartment (BrE: flat), appetizer (BrE: entree, starter), candy (BrE: sweets), chips (BrE: crisps), cookie (BrE: biscuit), eggplant (BrE: aubergine), jelly (BrE: jam). Elevator (BrE: lift), gasoline (BrE: petrol), movie (BrE: film), and others7.

Some words are typical of WcGA, as for example:

pop - carbonated beverages (widespread in West and North, while soda predominates in California, Arizona, southern Nevada)

davenport (widespread) - couch or sofa

Skid road or Skid Row (part of a city)

chechaco - derogatory word for new comers to the Northwest

crummy - a vehicle used to transport forest workers

tyee - Chief, boss, a person of distinction.

Some words – now, in general use - originated as American slang, as hijacking, disc jockey, bulldoze.

On the whole, GA is very rich in slang, and many words are widely known in the world all other varieties of English, as Yummy! (= tasting good), Hit me! (= another beer, please), joint (= hash cigarette), you bet! (= Of course!), shades (= sun glasses), play dirty (= be unfair), four-letter words (= invectives), square (= conservative uncool ), Good job! (= Well done!).

4. Syntax

Also in the

syntactic field WcGA/GA

show to be more conservative than BrE. For instance, during the 1700

speakers of English generally formed the past participle of get

as

gotten,

then in the 1800 BrE began to drop the –en

ending,

while most Americans continued using the older form gotten.

AS

MENTIONED, THIS IS MORPHOLOGY, NOT SYNTAX.

Regarding the use of the past simple, WcGA/GA show tend (THIS IS ABOUT G.A., NOT BRITISH ENGLISH, RIGHT?) to prefer forms as learned (BrE/learnt), burned (BrE/burnt). With the words already, just and yet, WcGA/GA use the present perfect (“I’ve just eaten”) or the simple past (“I just ate”), while BrE prefers the present perfect.

Another case in

which GA has been conservative and BrE innovating, is the following:

to a question like “Did

you leave the book at home?”

a BrE speaker could answer “I

may have done”

(using the word done

which has began being adopted during the 1950s by more prestigious

British people), while Americans would say “I

may have”

or “I

may have done so”.

GOOD

POINT. AND THIS IS SYNTAX

Tag questions are added to the end of a statement to convert it to a question, as in “You know what’s going on, don’t you?”

Where a statement involves two separate activities, WcGA/GA use “to go” + infinitive ( “I’ll go take a shower”), while BrE would use “to go and” + infinitive (“I'll go and have a shower”).

As regards the use of modals, in conversation, must, will, better and got to are less frequent than in BrE. However, to form the future, WcGA/GA mostly use the auxiliary will. In GA, when the main verb of a question is have, inversion has become ungrammatical (contrary to BrE), so a BrE speaker may ask either “Do have a pen?” or “Have you got a pen?”, while Americans would use the former.

Considering the noun phrase, WcGA/GA show the use of the amplifier real in pairs like real good and real fast; in conversation, American speakers prefer pretty, as in pretty good. Other words which can function as adverbs are now and immediately, but not in conjunctions.

A typical feature of WcGA/GA is the use of singular verbs with collective nouns as family, staff, committee, and names referring to sports teams, companies, organisations and institutions.

With noun phrases indicating point in space and time, WcGA/GA sometimes require an article, as in the next day, in the hospital. On the whole, there are differences from BrE also in the selection of prepositions, for example “it is different than mine”, (BrE: from); “a store on Main Street” (BrE: in); British sportsmen play in a team; American athletes play on a team.

In the journalistic field, American style is more tolerant of lengthy noun string modifiers.

5. Textuality

Among the systematic differences between British and American written texts, American written genres seem to be more colloquial and involved ??? than British ones, and also more nominal and jargony than the latter.

As regards conjunctions, some of the most used in WcGA/GA are and, but, for, nor, or, so, yet; after, although, as, because, before, how, if, once, since, than, that, though, till, until, when, where, whether, while; both...and, either...or, neither...nor, not only...but also, so...as, whether...or.

Regarding writing conventions, while WcGA/GA tend to use Mr., Mrs., St., Dr., BrE often prefers Mr, Mrs, St, Dr. Moreover, Americans place commas and periods inside quotation marks, while question marks and exclamation points follow the British convention to be placed inside if it belongs to the quotation and outside otherwise.

6. (Normative) pragmatics

From a pragmatic point of view, WcGA/GA show various ways of using the language during interactions, as for instance to express preferences, order something to drink, express congratulations. For example:

Americans typically use “Yummy!” to say something is good tasting;

“You bet!” means of course;

“good job!” (BrE “well done!”);

“it is a four-letter word!” means it is an invective;

if something is “hot” means it is good;

a “square person” is a conservative.

Americans use “definitely” or “I’m sure” to express strong assertions;

In answering a question like "Tea or coffee?", if either alternative is equally acceptable, an American may answer "I don't care", while a British person may answer "I don't mind";

Older BrE often uses the exclamation "No fear!" where current AmE has "No way!";

The expression "I couldn't care less" is used in WcGA/GA and BrE, however, in WcGA/GA it is possible to say "I could care less", meaning the opposite.

GA is rich in idioms and colloquialisms. Some typical colloquialisms of American origin are cool, have a nice day!, sure!. Idioms coming from the United States are take for a ride, take a backseat, have an edge over, take a shine to, inside track, bad hair day, it ain't over till it's over, what goes around comes around.

Among the English idioms that have essentially the same meaning, but show lexical differences between the British and the American version there are:

sweep under the carpet (BrE) /sweep under the rug (GA)

see the wood for the trees (BrE) / see the forest for the trees (GA)

skeleton in the cupboard (BrE) /skeleton in the closet (GA)

a drop in the ocean (BrE) / a drop in the bucket (GA)

storm in a teacup (BrE) / tempest in a teapot (GA)

haven't (got) a clue (BrE) / don't have a clue or have no clue (GA)

On the occasion of holidays greetings, when Christmas is mentioned in a greeting, Americans use to say Merry Christmas, while British also use Happy Christmas. Furthermore, it is common for Americans to say Happy Holidays, referring to all winter holidays (avoiding any specific religious reference), while British rarely use it.

ACTUALLY, PRAGMATICS (EVEN

NORMATIVE PRAGMATICS) IS NOT A QUESTION OF COLLOQUIALISMS, SUCH AS

THE ONES THAT YOU GIVE HERE (AND WHICH ARE A LEXICAL PHENOMENON).

AN EXAMPLE OF PRAGMATICS: GA/SBE > DIRECT ORDER /

INDIRECT ORDER

Bibliography and links:

Hogg M. R., Denison D., 2006, A history of the English language, Cambridge University Press.

(partially available on: http://books.google.it/books?id=U5FDi8WksqYC&pg=PA396&dq=%22american+english%22+syntax&lr=)

Hogg M. R., Blake N. F., Algeo J., Lass R., Romaine S., Burch R. W. , The Cambridge history of the English language, (partially available on: http://books.google.it/books?id=ia5tHVtQPn8C&pg=PA326&dq=%22american+english%22+syntax&lr=)

Onesti Francovich N. e Digilio M. R., 2004, Breve storia della lingua inglese, Carocci, Roma, pp. 83- 85.

http://www3.hi.is/~peturk/KENNSLA/02/TOP/rhoticism.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WIhMufAZV8&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bN5nVmhYyZw

http://www.seattlepi.com/local/225139_nwspeak20.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/grammar/learnit/learnitv165.shtml

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_and_British_English_differences#Use_of_tenses

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_and_British_English_spelling_differences

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_American

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_English_regional_phonology#Pacific_Northwest_English

http://www.effective-english.eu/resources/which_english.html

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Atlantis/2284

http://reese.linguist.de/English/america.htm

1 Map adapted from http://www.seattlepi.com/local/225139_nwspeak20.html

2 “Rhotic: of an English accent, pronouncing the letter r wherever it appears, as in bar or barred; this trait is common in much of the United States, many parts of the north of England, and Scotland.” (http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/rhotic)

3 See also http://www.fonetiks.org: this site offers pronunciation guides to 9 varieties of the English language, including American English.

4 In the interrogative, are is omitted in second person singular and first and second person plural.

5 “Wanna” can be used with all persons singular and plural, except third person singular.