†††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††† WATERCOLORS at POSADA

I just painted a few watercolor drawings while

bicycling through the countryside of Posada, at the back of its hill, toward

Orvile. From the same place where I was standing, I

represented the views in four different directions: a dusty path among

cultivated fields, some bushes with violet flowers, a

slope to a ridge of the Posada river (the same name as the town), and

the town itself, perched on top of its promontory,

seen from beside a few tall trees, maybe birches. Then I moved, by

bicycle again, and I made a drawing of another view of

the ancient fortress of the town, at the very top of the hill, from

a closer and lower position.

I was basically painting watercolors in one go, that

is without tracing the pencil outline first. Even though it has been several

years now that I have used watercolors, I had never

happened to paint any coloring immediately, without an initial drawing

by pencil. If nothing else, not on a regular basis as

I have done over the past 2 or 3 days.

Not all the drawings came out very well, some donít

look too significant to me; others, however, are very interesting. Inde-

ed, in some cases, some paintings turned out to be

much more suggestive that I carried out most of all by chance, or as an

exercise, than others to which I dedicated more effort

and accuracy. Usually, I very much appreciate watercolors painted in

this fashion, so that they hint at the subject

represented, they give a sensation of it, rather than depicting it precisely

and in

detail. Not just the ones that Iíve made myself these

days, I mean, but in general. Just as I have always been fascinated by

drawings barely sketched and roughly outlined, which

however effectively synthesize the object portrayed, or an aspect of it.

I thought, lately, that the reason why I enjoy similar

watercolors could indeed be the fact that there isnít a linear drawing of

the various traits and aspects of the object, traced

with rationality and a more or less logic thought, to be subsequently col-

ored in its distinct parts. In the initial pencil

drawing a selective analysis of the object already takes place: one

distinguishes

the traits of it, its horizontal, vertical and

inclined lines, straight stretches and curves, which constitute it with regard

to the

eye that looks at it. After that, one takes care of

the colors, the shadings, of the lights and the shades. The operation of dra-

wing and then coloring, therefore, which by the way usually

takes me more time, is more rational, logic and deductive than

the coloring in one go.

In fact, if I start off immediately by dipping the

brush into the water and the watercolour, and I lay brush-strokes of color

on the white sheet of paper, I do far less conscious

analysing of what I am depicting. The lines, the volumes, the colors,

that is the light and the shades which portray nature,

become one in the immediate watercolor. In order to represent a body,

an entity that appears to me in the light, all I have

is colors and brush strokes. If a surface is wide, I will lay several traces,

one next to the other. In order to darken the color in

a shady area, I may make several passes over it, or get the most out of

the doses of water and color. All this while I am, at

the same time, drawing and coloring, in one coherent operation. That is

to say I am representing in color what I am seeing.

That is, maybe more precisely, at least with regard to the other operation,

I am producing a sensation of what I see. A

watercolour painted in this fashion is more felt than thought of. It is a

sensation

more than a thought.

In a watercolor drawn out beforehand, and then colored

in, I may very much admire the accuracy of the outline, the precision

of the trait in detail, and the integration of this

linear analysis with colors, which give reality, depth, and further information

a-

bout the representation.

In a watercolor made in one go of brush strokes, I may

admire the istinctive synthesis of the view, which communicates an

emotion much more than a thought; if it still implies

an analysis, it is a non-linear type, but one that is comprehensive, total,

unconscious, and on several levels

simultaneously.†

I believe, eventually, that it is about two different

types of practices, which pursue different goals, to a greater or lesser

degree,

at disposal of the one who may want to take advantage

of watercolors in order to portray nature.††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Posada viewed at the foot

of† its hill †††††††††††††††††††††††††† †††††††††† ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

The town seen from a path of

the countryside, toward the sea

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††

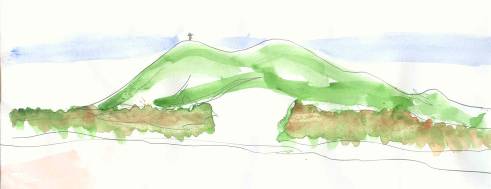

The hill seen from a path of the

countryside. This watercolor††††††††††††††††††††††††††† View of the

is one of the few, of this

occasion, in which I traced an outline.†††††††††††††††††††††††† church

††††††††††††††††††††††††† †

††††††††††††††††††††††††† †

From the beach††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

The hills behind Posada, toward the hinterland , and a pond

†††††††††††††††††††††††

†††††††††††††††††††††††

The ďbreastĒ mountain viewed from

the pond††††††† †††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††Some

green by the road side

†††† ††††† Some green on a ridge of the Posada

river†††††††††††††

††

††

Another watercolor with an

outline

††††††††††††††††††††††††

††††††††††††††††††††††††

A country path among the

fields†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

Slope to a ridge of the Posada river

†

From PAINTINGS

to VIDEOS††††††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††HOMEPAGE