VISIT TO TWO APARTMENTS

OF THE UNITE’

D’HABITATION

IN MARSEILLE

Premise:

Following

is an account of a visit to a renowned and important building of the history of

architecture, which is called Unité d’habitation, meaning “Housing Unit”, and

it was designed by the French architect Le Corbusier, who lived and worked in

the past century, in France and all over the world, and is one of the fathers

of modern architecture. The Unité was brought into being between 1946 and 1952,

and consists of a big residence building, with apartments of several different

arrangements and dimensions, and for the most part laid out on two floors,

connected by an interior staircase. They are integrated by a number of common

services, available to all the inhabitants of the building and also to any

users from outside, such as stores of basic needs, offices, professional

agencies, a hotel, and common rooms dedicated to several purposes. These

services are mostly located on the third floor of the building, which for this

reason has a particularly collective and public character with respect to all

the others. Moreover, on the terrace-ceiling are also a kindergarten school, a

gym, a track for outdoor jogging and an open-air theatre.

The

visit takes place in two different dwellings, of opposite arrangements of

spaces: in the first one, one enters from the common corridor of the building

into the lower floor of the apartment, and mounts the staircase to reach the

floor of the bed-rooms; in the second one, instead, one walks in on the upper

floor, and the staircase descends to the other floor, which is therefore below

the entrance level.

I am standing in front of the

Hotel Corbusier, on the third floor

I am standing in front of the

Hotel Corbusier, on the third floor

of the Unité d’Habitation, on Boulevard Michelet in Marseille;

it is about 9 o’clock of night, of August 23rd 2006. I’m

seeing

through the glass window a young man, probably 25-years-old,

who is setting the last glasses in place behind the counter of the

bar in the hall. After that, he heads for the desk by the entrance

of the hotel. The large wooden door, enclosed in an entirely glass

wall, is flung open, so I step closer:

-“Excuse me”, I address him in my awkward French, “you are

all full, aren’t you?”

- “Yes…”

- “Yes, I know, I had called. I wanted to ask: is it possible to

visit an apartment?”

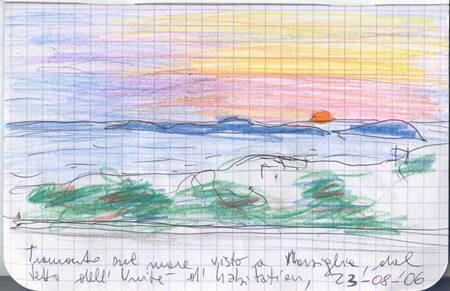

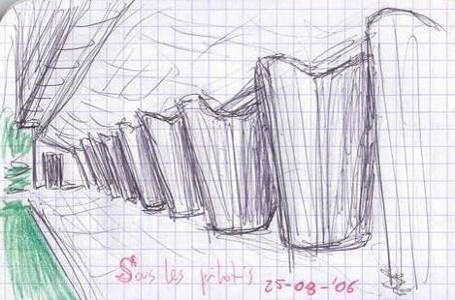

Sketch of the seaside that I made from the

roof of the building, minutes before going to the hotel.

He kindly answers that it is, and that it costs 5 euros (which I al-

ready

knew). To tell the truth, he adds, it would be possible to

visit two of them: “One which is descending, and another one

ascending”, that is one which has the entrance from the “rue inté-

rieure” (‘interior street’) on the lower floor and the bedrooms on the

upper floor, and the other one with the entrance above and

the bedrooms on the floor below.

“Tomorrow morning, about 10 o’clock”, and he scribbles on a piece of

paper the numbers of the apartments and the floors on

which they are located.

-“Thank you, bye-bye!”

The morning after I arrive on time at the first one of the two, on a

higher floor. A middle-aged lady answers the door, in a night

gown and with her hair all messed up, looking as if she woke up not too

long ago. After a moment in which I tell her the reason

why I’m standing there, she takes cover behind the door, and asks me to

come back later. Evidently, she was not expecting any-

body.

- “At what time?”, I ask her

- “In an hour”

- “Ok, I’m sorry, bye-bye!”.

I therefore descend to the second apartment, on a lower floor. I

ring the bell, and a tall, thin lady opens the door, closely followed by

her son who, as I will find out later, is 9-years-old, and whose name is

Gervaso (which I just made up right now). I ask her if I may visit the apartment, as they told me at the hotel. - “It is 5 euros!”, Gervaso promptly informs me. - “Yes, I know”, I answer him. The lady reproaches him, also for saying other things which I did

not quite catch. She sends him back inside, while he proves to be a

cheerfully lively and rebellious charac-ter. I smile, the scene strikes me

as somewhat amusing. The lady half-closes her eyes, as she is glancing down the hallway,

and with a medita-tive expression she tells me that she can start the visit

with me, and then proceed with other people that she had already planned to

receive. I hand her the 5 euros and we walk inside. The immediate impression that I get at the first glance inside the

apartment is the same one which I felt yesterday while peeking through a

glass window into the studio of an architect on the third floor: “ The

width here is double”, I thought, “They must have knocked down a wall

between two different spans and obtained a whole double-mea-sure space.” It

just seemed so abundantly large to me. Well, no, instead. It was a plain

typical width of

While she begins explaining to me the entrance and the kitchen,

Gervaso takes amusement in provoking, turning the radio on as she is

speaking, or singing straight out loud. She yells at him to go upstairs and

later on, when other people arrive, he will finally mo-ve there. I really

enjoy Gervaso. More than his mother, I must admit, who is so critical about

the building and Le Corbusier with observations that are often blunt and

coarse. As soon as we walk in she praises the narrow entrance space,

because it functions as an air chamber between the “rue intérieure” and the

living-room, effectively warding off noises and sounds. Not that the “rue

inté-rieure” appeared to me as a particularly noisy place, or, in any way,

as if it is inhabited any more than to just walk past, but of course, I

don’t live there. She accurately illustrates the kitchen, and she tells me that she

doesn’t often shop at the little supermarket on the commercial

floor, as she prefers the ampler variety of products of a larger store

outside the building. She will turn to the shop on the third

floor in particular cases or when in urgent need.

We move on to the living room. She criticizes the heating vents, saying

that they are too high (the height of a man). I can under-

stand that, at floor level they probably might have been more effective.

She shows me the loggia very satisfactorily, pointing out that she is

probably the only inhabitant who will open it all the way up

in the summer, letting the living-room space freely flow outside. In a

niche in the wall I notice a picture of the Heidi Weber

pavilion. Someone rings the bell at the door, the lady opens it up and there

is a group of about ten students, accompanied by professors, coming from

the - “You can start over again, if you like”, I speak up. - “Are you sure? That is very

kind of you! You can take pictures, in the meantime. Do you have a camera

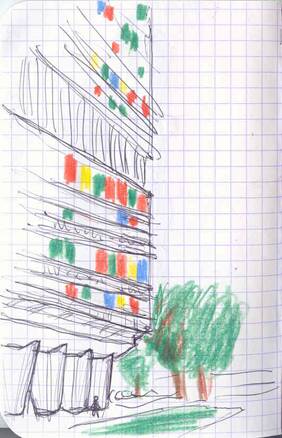

with you?”, and she points at my backpack. - “No, I don’t have one, but you can start over again”. I actually

didn’t have any camera with me, I made some sketches, instead, (few) of the

outside of the building. She then returns to illustrating the entrance and the kitchen. Here

she reprehends with a loud voice the commercial floor of the building,

recounting that at the beginning there were many more stores than right

now, and that a number of those have in time been replaced by offices and

studios, among which the ones of several architects. - “Now it is an almost dead zone!”, she asserts. I reply nothing,

much to my sorrow. I don’t breathe a word at any of the criticism that she

expresses, at times in a rather thea-trical manner, throughout the visit.

Maybe even now, with all that company, I wouldn’t say anything. After all,

for a woman who is at the moment alone with her kid, in her own home, one

should have some respect and comprehension. But still I regret it, because

even though that zone is not one of those with the heaviest traffic of

inhabitants in the whole building, it is all but “presque morte”. The group of the newly-arrived take pictures of the living-room,

while the lady describes,

among other things, the terrace roof, and there goes another

critique at the theatre: - “Le Corbusier sought to add a cultural note to the roof with the

theatre, but it doesn’t work as a theatre, it is small”, she claims, repeating the expression “note culturelle”. It is evident to me that

it is not meant to work as an actual theatre, with so much as a scene and actors, but as a podium for events, celebrations, parties,

reunions… We approach the staircase, where she points out to us the accurate

detail of the handrail, low on the outside for the children, at hip-height against the wall for the adults. After that, everybody is

upstairs, in the parents’ bedroom, from which one can look out the great window, toward the mountains outside, or downstairs,

toward the living-room below. Every now and then the lady looks around for

me and asks me if I am following, since I was “so kind as to let her start

the explanation over again”. We then move to the passage area between the different bedrooms, on

which overlook the technical room for the water-heater (individual for every apartment), and the shower for the kids, which

is provided with an entrance door that resembles those of boats or caravans. It is incredible how a work of this magnitude,

which hosts 1600 people, is so accurate in its details, so refined and meticulously elaborate in its layout of spaces inside the single

apartment. Since she doesn’t seem to me to be sparing criticism and complaints

about the place where she lives, as I walk into Gervaso’s bedroom I inquire if the sliding partition wall between the two

bedrooms is preferably kept open, or also comfortably closed. - “Oh no, c’est bon!”, she answers, indicating how it is not

necessary to keep it open in order to obtain a larger space. I didn’t reply to any of her critiques, and in return she reassured me about

a doubt inherent in my question. I probably felt that way be- cause of the number of people present in the same place at the same

moment. The visit to the first apartment is finished, the group of students

and I take yet another glance around at the rooms of the upper floor, and then I say: “Au revoir, Gervaso!”, who is lying on his

bed, reading an Asterix comic book. “Au revoir”, he answers af- ter a student also says hi to him. Then we descend, we say good-bye,

and we leave.

I also part from the Dutch group, and I make my way to the higher

floor again, since in the meantime it has come to be 11 o’clock. I ring the

door bell, the same lady appears, all dress- ed and ready. I walk in and I pay the fee. In this tour also I am guided by a lady, and this time I am alone.

The route through the house is practically identical to the pre-vious one,

except for the fact that here you descend to the bed-room floor, instead of

going up. The attitude toward the building and its architect is quite

differ-rent. There are critiques here also, but the tone is definitely more

respectful. She shows me the kitchen. She points out to me how the cabinet

communicating between the inside and the “rue intérieure”, for the

distribution of products from the stores and the common services, doesn’t

carry out its original function any more, and it is

is now closed and used as a cupboard. Neither do the ice supplies get

delivered individually to the apartments any longer after the

invention of the refrigerator.

- “But for that time, it was good”, she comments.

She explains to me that the heating vent at eye-level is still working,

evidently causing no bother as in the other apartment.

- “That’s nice!” I observe about a couple of shelves composed together

and hung on the living-room wall.

- “It’s Charlotte Perriand who made those. You know her?”

- “Yes, yes…not personally, but yes.”

She points at a lamp as tall as a man, by Vico Magistretti,

- “You know him?”

- “Yes, yes…not personally, but yes”.

Her apartment, as well as others in the building, does not have the

double-height space ( - “It wasn’t very practical”, she says, explaining the reason why

the mezzanine was extended as far as the glass window of the loggia,

eliminating the double-height space. - “Yes, otherwise the parents’ bedroom could have been closed in”, I

suggest, thinking that, even though I understand the observation, I

wouldn’t have given up on the double-height space. In the meantime we’ve descended downstairs, after she told me that

the staircase is Jean Prouvé’s work (“he died with no money”). Since the

dining area and the living-room are all located upstairs, the parents’

bedroom turns out to be quite ample.

- “This is nice too!”, I exclaim, observing the niche in the wall in the

same spot of the present floor as the shelves by

Perriand that we just saw upstairs.

- “Oh, the niche was already there, and then my husband made the shelves

and colored them!”. It is all white, with rectangles co-

lored in red, blue and yellow.

- “I like to make white things with the primary colors too”, I add, and

my stiff and awkward French isn’t getting any better.

As she is starting to make for the children’s bed-room she walks by the

bathroom:

- “This I will show you later”.

I gather that it is occupied, even though I haven’t seen anybody else in

the house.

- “Oh no, come on in, if you like!”, shouts a man’s voice from inside

the bathroom. At that, the lady opens the door, and I, from

outside where I am, see a man, with his shoulders turned to the door,

who is combing the long hair of a little girl standing in the

bathtub, wearing a bathrobe.

- “Bon jour!”, I exclaim in a loud voice, “Je suis Italian! (‘I am

Italian’)”. I don’t know why I add this particular fact, but if no-

thing else, I excuse myself for any howlers in French that I might make.

- “Oh!”, answers the gentleman, “Welcome!”. Merci, I’ll say to you now.

The 5 euros that I paid for the visit didn’t have much

to do with that moment.

After seeing the bathroom, we turn toward the kids’ bedrooms. We walk

through the passage area, where I am shown another

ter-heater and another shower. The bed-room doors are joyfully colored.

- “A red and a yellow door! This is beautiful! It is radiant!”, I cry

out.

As we move through the bed-rooms of the little girl, about 10-years-old

I believe, and her sister of 20, who is now not at home,

we step out into one of the two loggias. From right here you can enjoy

the beautiful view of the park at the bottom of the building,

and of the mountains in the distance. She explains that there are

“perroquets” in the trees of the park. I draw the dictionary out of

my backpack to check on the translation of that, and I’m surprised that

it is ‘parrots’ that are flying around at a short distance.

After that we set out for the exit of the apartment. I tell her that I

had visited the building already 8 years ago, but having composed

some projects inspired by Le Corbusier’s works, I wanted to see it

again, also because many aspects and details I did not know

the first time. She hands me her visiting card and I walk out.

A few hours later, I am still inside the building, on the third floor,

after several ascents and descents again, and trips in length and in

width. To tell the truth, I have visited every place, or almost, that it

is possible to visit.

As I am approaching the elevators to go down again, I turn around a

corner and I find myself in front of the lady of the second

apartment I visited, while she is discussing with a man.

- “Bon jour!”, I exclaim, surprised and glad to see her again. I call an

elevator, I wait a few minutes, and I move toward the first one

that appears. She is still talking, and I don’t want to bother her, so I

walk into the elevator without saying anything. As the doors are

closing, I realize that she is looking at me, so I say: “Au revoir!”,

glad in the same way, raising my hand. At that moment I thought,

even though I had not made the decision before, that I would descend to

leave, that visit to the Unité d’Habitation finished as well.