|

|

|

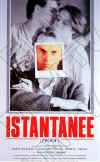

Proof - Istantanee, 1991 Proof - Istantanee, 1991

|

|

La curiosa storia di un uomo cieco che scatta fotografie

per avere la prova che il mondo e' davvero cosi' come gli altri glielo

descrivono |

|

| Titolo

originale: |

Proof |

| Nazione: |

Australia |

| Anno: |

1991 |

| Genere: |

Commedia |

| Durata: |

|

| Regia: |

Jocelyn Moorhouse |

| Sceneggiatura: |

Jocelyn Moorhouse |

| Musiche: |

Waving Not Drowning |

| Fotografia: |

Martin McGrath |

| Montaggio: |

Ken Sallows |

| Scenografia: |

Dimity Huntington |

| Costumi: |

Kerry Mazzocco |

| Cast: |

Russell Crowe

(Andy) |

|

Hugo Weaving (Martin) |

|

Genevieve Picot (Celia) |

|

Heather Mitchell (madre

di Martin) |

|

Jeffrey Walker (Martin

da piccolo) |

|

Daniel Pollock (punk) |

|

Frankie J. Holden

(Brian) |

|

Lisa Chambers

(infermiera) |

|

Belinda Davey

(dottoressa) |

| Produttore: |

Lynda Hoouse |

| Produzione: |

Australian Film

Commission, Film Victoria, House & Moorhouse Films |

| Distribuzione: |

Fine Line Features |

|

Proof

la trama

Martin, cieco, vive solo,

accudito da una governante, Celia. Martin ha l'abitudine di scattare

fotografie, per poi farsi descrivere cio' che ha ritratto e prendendone

nota nel linguaggio braille. E' legato a Celia da uno strano rapporto di

odio/amore. Lui sa che lei lo desidera, e sembra trarre piacere dal

trattarla male, respingendola. Un giorno conosce Andy, lavapiatti in un

ristorante, e inizia a farsi descrivere le sue foto da lui. All'inizio

riluttante, Andy finisce per diventare la persona della quale Martin si

fida di piu', per la sua integrita' morale e la sua schietta semplicita'.

I due finiranno per diventare amici. Ma Celia, sempre disperatamente

innamorata di Martin, e' in agguato. Si scopre che lei, mentre Martin

passeggia e scatta le sue foto casuali, a sua volta insegue Martin di

nascosto e lo fotografa. Un giorno Martin inconsapevolmente la fotografa.

Quando mostra quella foto ad Andy, questo per coprire il segreto di Celia

mente per la prima volta a Martin su cio' che e' ritratto nella foto.

Prendendo spunto da questa breccia che si crea nel rapporto di totale

fiducia reciproca nel rapporto tra Martin ed Andy, Celia seduce Andy,

facendo in modo che Martin li scopra; poi invita Andy a casa sua, dove

Andy, orripilato, trova le pareti coperte di fotografie che Celia ha

scattato ad un inconsapevole Martin, e si rende conto di essere stato

usato da Celia che era gelosa del rapporto creatosi tra i due uomini.

Martin, che basa la sua vita sulla completa onesta', si allontana da Andy

e licenzia Celia. In seguito pero', ci sara' un riavvicinamento con Andy,

e quindi si chiude con la speranza che l'amicizia e la fiducia reciproca

potranno essere recuperate.

|

|

Nel 1991, Russell Crowe ha vinto il

premio come miglior attore non protagonista dell'Australian Film Institute

per Proof

|

|

|

|

|

le tre ultime immagini sono tratte da Russell

Crowe slideshows

|

|

Recensione dal New York Times, 3 gennaio 2001

TACCUINO DEL CRITICO

‘Proof’: l’interruzione di un circolo

doloroso di Odio ed Amore

DI ELVIS MITCHELL

Il film australiano “Proof” del 1991 comincia con

una serie di fotografie che sono frammenti sensuali, ritratti che rivelano

solo parti di un mondo e trasmettono una disperazione che il resto del

film si dispone ad esplorare in modo essenziale, intelligente ed

umoristico.

L’immaginifico e straordinariamente soddisfacente

film del debutto cinematografico della scrittrice e regista Jocelyn

Moorhouse è così buono che provoca una domanda : che cosa le è

successo? L’itinerario della sua carriera negli anni successivi sembra

provare che non c’è posto nelle sedi istituzionali del grande cinema

americano per una donna capace di lavori così essenziali e seducenti.

“Proof”, che la Film Society del Lincoln Center

presenta con un’unica proiezione domani sera alle 7.30 per commemorarne

i 10 anni dall’uscita, ha il tipo di complessità che rende il film

difficile da vendere persino come film d’autore. Il film di Ms.

Moorehouse è un melodramma romantico con un substrato di paura, gelosia e

relatività della verità, reso vivo attraverso il triangolo che coinvolge

Martin, un cieco paranoico (Hugo Weaving); la sua governante, Celia (Genevieve

Picot); e Andy, il lavapiatti che entra nelle loro vite (Russell Crowe).

Martin e la sua governante conducono un’esistenza

conflittuale - le maniere caustiche di questa nascondono a malapena il

desiderio che prova per il suo datore di lavoro, che ne è a conoscenza e

gioca con lei continuando a tenerla al suo servizio. Entrambi si torturano

a vicenda, sinchè l’innocente Andy capita nella loro piccola guerra e

diventa il cuneo che ciascuna parte usa contro l’altra. Andy è il

raggio di luce che penetra il loro oscuro Giardino dell’Eden, e le cose

non saranno mai più le stesse per Martin o Celia dopo il suo arrivo.

Ms. Moorehouse dissemina queste fosche premesse di

dettagli comici - la sua ripresa dell’amore è costellata dagli

inconvenienti che l’ossessione causa. ”Proof“ è altrettanto

caratteristico dei film di Pedro Almodovar, sebbene senza la sua assoluta

assurdità. Questo non significa che “Proof” non sia pieno di tratti

singolari. Martin porta in giro la sua macchina fotografica per riprendere

avvenimenti della sua vita - che si fa descrivere e che cataloga in

Braille per avere una prova fisica degli avvenimenti. “La prova che

quello che c’è nella fotografia è quello che c’era qui,” dice,

come brusca spiegazione. (Andy non sa come prendere questa inclinazione di

Martin: “C’è un sacco di gente qui,” dice nervosamente Andy la

prima volta che Martin tira fuori la sua macchina fotografica).

“Proof” diventa un po’ semplicistico e

sentimentale solo quando Ms. Moorehouse cerca di spiegare la devozione di

Martin alla sua arte fotografica. Ella struttura il film in modo da dargli

meno peso di quello che un più convenzionale filmaker farebbe, usando dei

flashback che fluttuano attraverso il copione e poi vengono spazzati via

come fiocchi di neve nel turbinare dei momenti che si affastellano durante

il film. I suoi momenti climax sono molto più ingannevoli e raggiungono

lo scopo attraverso un’astuzia sottotono.

Il tocco agile di Ms. Moorehouse conduce a scene che

possono rivaleggiare con la tendenza di Almodovar di strappare fuori l’umorismo

dalla sessualità. Un’enorme ombra sullo schermo appare sopra Celia - un

clichè che qui è sollevato del suo tono sinistro; invece l’oscurità

avvolgente causa un freddo sorriso di anticipazione sul viso di Celia. E,

alcuni momenti prima, disturbata dal’intrusione di Andy, Celia passa al

setaccio i libri di Martin e mette assieme un ritratto cubista di Andy con

pezzi che ha selezionato del suo viso dalle foto di Martin.

“Proof” potrebbe essere facilmente liquidato come

un felice incidente, una realizzazione da una-volta-nella-vita dei doni

che un artista ha da offrire. Ma il film è colmo di indizi di segno

opposto, ad esempio l’agio che dimostra Ms. Moorehouse con i suoi

attori. Mr. Crowe qui è leggero ed appassionato - “Proof” è stato

realizzato prima che decidesse di limitarsi ad un sorriso per film. Mr.

Weaving ha un viso lungo e sottile con una fronte ampia e la bocca

prominente che gli aggiunge sensibilità; sembra esprimere il dolore come

farebbe un cieco, senza avere idea di come il dolore irrompa

improvvisamente quando la sua abituale espressione impassibile, una

maschera di alterigia indifferente, si rompe.

Ms. Picot ha la veloce alacrità della giovane Glenda

Jackson e la sua voce ha una simile risonanza autoritaria.

L’eleganza triste del film non può essere nemmeno

liquidata come un caso. La sua atmosfera è resa più profonda dal tema

musicale intorbidante suonato dalla band australiana “Not Drowning,

Waving”, che può fluttuare delicatamente come una brezza e poi colpire

come un improvviso scoppio di tuono. (il CD della colonna sonora, che è

un po’ più insistente della musica del film, vale la spesa, come anche

“Hammers” una colonna sonora che la band fece per un film minore di

Mr. Crowe “Hammers over the Anvil”).

La triste ironia è che la carriera di Ms. Moorehouse

si è impantanata durante una decade che è ampiamente - ed

inaccuratamente - considerata l’era del film d’autore negli Stati

Uniti e che per caso include qualcosa detto Anno della Donna. Ancora più

ironico il fatto che, grosso modo nello stesso periodo in cui il film “Proof”

stava languendo, film come “Strictly Ballroom” di Baz Luhrmann ed “Il

Matrimonio di Muriel” di P.J. Hogan venivano importati dall’Australia

ed il popolo dei cinema veniva bersagliato dalla loro pubblicità.

“Proof” può non essere stato aiutato dal titolo,

che, sebbene duro ed appropriato, sembra evocare altri lavori per molte

persone. Quando parlo di questo film, la gente mi chiede se sia parte del

canone di Hal Hartley, l’uomo che ha fatto del titolo di una sola parola

il suo Idaho privato. Quando Ms Moorehouse arrivò negli Stati Uniti fu

gravata da adattamenti affettati e consce della loro importanza quali “Come

fare un quilt americano” e “Un migliaio d’acri”.

Dopo essere sopravvissuta a questi film, Mr. Moorehouse

avrebbe potuto comprensibilmente decidere che non voleva nemmeno più “vedere”

un film, figuriamoci girarne uno. E dopo un anno in cui il miglior

risultato raggiunto da una donna nel campo del cinema è “What Women

Want”, “Proof” è più che una ventata d’aria fresca. E’ un

intero serbatoio di ossigeno.

|

'Proof': Bitter Cycle of Love and Loathing Interrupted

By ELVIS MITCHELL

The 1991 Australian film "Proof" begins with a series of photographs that are sensual

shards, pictures that reveal only pieces of a world and convey a desperation that the rest of the film sets out to explore with

economy, intelligence and humor. The inventive and extraordinarily satisfying feature-film debut of the writer and director Jocelyn Moorhouse is so good that it provokes a

question: Whatever happened to her? Her career trajectory in the years that followed seems to prove that the American mainstream movie establishment has no place for a woman capable of such beguiling and spare work.

"Proof," which the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting in a single showing tomorrow night at 7:30 at the Walter Reade Theater to commemorate the decade since its

release, has the kind of complexity that made the movie difficult to sell even as an art-house

presentation. Ms. Moorhouse's picture is a romantic melodrama with a subtext of

fear, jealousy and the relativity of truth, brought to life through a triangle involving

Martin, a blind paranoiac (Hugo Weaving); his housekeeper, Celia (Genevieve

Picot); and Andy, the dishwasher who enters their lives (Russell Crowe).

Martin and his housekeeper lead a combative existence - her caustic manner barely covers her desire for her

employer, who knows that she wants him and toys with her by keeping her on. They both torture each other until the innocent Andy wanders into their little war and becomes a wedge that each side uses against the

other. Andy is a shaft of light penetrating their shady Garden of Eden, and things are never the same for Martin or Celia after he shows up.

Ms. Moorhouse seeds this grim-sounding premise with comic highlights - her take on love is filled with the stumbles that obsession

causes. "Proof" is as distinctive as Pedro Almodóvar's films, though without his full-on

absurdity. This doesn't mean that "Proof" isn't ripe with

singularity. Martin carries a camera around and snaps pictures of events in his life - which he has described to him so that he can label them in Braille - not because he wants to keep an album of Kodak moments but because he needs physical evidence of the

events. "Proof that what's in the photograph is what was there," he

says, by way of curt explanation. (Andy doesn't know what to make of

Martin's bent: "There's lot of people here," he nervously blurts the first time Martin whips out his

camera.)

"Proof" gets a bit simplistic and sentimental only when Ms. Moorhouse attempts to explain

Martin's devotion to his photographic craft. She structures the film to give this less weight than a more conventional filmmaker

might, using flashbacks that float through the scenario and then fly off like snowflakes in the blizzard of moments that pile up through the film. Its climaxes are far more insidious and succeed through low-key

cunning.

Ms. Moorhouse's agility leads to scenes that rival Mr. Almodóvar's penchant for wringing humor out of

sexuality. A huge on-screen shadow looms over Celia a cliché that is here relieved of its ominous tone;

instead, the enveloping darkness brings a coldblooded smile of anticipation to

Celia's face. And earlier, disturbed by Andy's intrusion, Celia goes through

Martin's books and assembles a Cubist portrait of Andy that she has culled from pieces of his face in

Martin's snapshots.

"Proof" could be written off as a happy accident, a once-in-a-lifetime realization of all of the gifts that an artist has to

offer. But the picture is filled with indications to the contrary, like Ms.

Moorhouse's ease with her actors. Mr. Crowe is eager and lithe here -

"Proof" was made before he began to limit himself to one smile per

picture. Mr. Weaving has a long, thin face with a large forehead and a prominent mouth that adds to its

sensitivity; he seems to register hurt as a blind person might, with no idea how pain bursts through when his usual impassive

expression, a mask of indifferent haughtiness, cracks open. Ms. Picot has the swift alacrity of the young Glenda

Jackson, and her voice has a similar authoritative resonance.

The film's moody elegance can't be dismissed as a fluke either. Its

atmosphere is deepened by the roiling score played by the Australian band

Not Drowning, Waving, which can waft as delicately as a breeze and then

slam like a thunderclap. (The CD soundtrack, which is a bit more insistent

than the music in the movie, is worth having, as is "Hammers," a

score the band did for a lesser movie starring Mr. Crowe, "Hammers

Under the Anvil."

The sad irony is that Ms. Moorhouse's

career stalled during a decade that is widely — and inaccurately —

considered to be the era of the art-house picture in the United States and

that also happened to include something called the Year of the Woman. Even

more ironic, at roughly the same time that "Proof" was

languishing, movies like Baz Luhrmann's "Strictly Ballroom" and

P. J. Hogan's "Muriel's Wedding" were imported from Australia,

and moviegoers were assaulted with publicity about them.

"Proof" may not have been helped

by its title, which, while stark and appropriate, seems to evoke other

works for many people. Whenever I bring the movie up, people ask me if it's

a part of the canon of Hal Hartley, the man who has turned the one- word

film title into his own private Idaho. When Ms. Moorhead came to the

United States to work, she was saddled with plummy, self-important

adaptations like "How to Make an American Quilt" and "A

Thousand Acres."

After surviving those pictures, Ms.

Moorhouse understandably might not even have wanted to see a movie again,

let alone direct one. And after a year in which a woman's peak filmmaking

achievement is "What Women Want," "Proof" feels like

more than a breath of fresh air. It's an oxygen tank. |

|

|