| |

by Paolo Emilio Landi

In 1744, Carlo Goldoni was a young lawyer in Pisa, and theater had not yet come to him as a profession.  Then Antonio Sacchi, an actor well-known for playing the role of Truffaldino, asked Goldoni to write a scenario for him. Then Antonio Sacchi, an actor well-known for playing the role of Truffaldino, asked Goldoni to write a scenario for him.

According to the tradition of commedia dell'arte, which started about 200 years earlier, the lines of each role were not to be written by the author, but improvised by the actors. Goldoni wrote the plot for the theater troupe and the company left on tour. Four years later, the Venetian playwright met Sacchi and his company again. During this encounter, Goldoni watched the company perform the scenario he created and he transcribed the impromptu lines of the actors.  This is the unique story of this play which came from the stage to the page, rather than the other way around. This is its secret; the source of its never-ending success. This is the unique story of this play which came from the stage to the page, rather than the other way around. This is its secret; the source of its never-ending success.

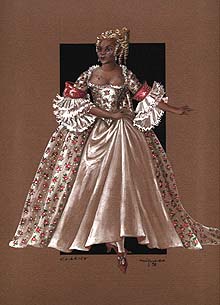

Theater companies of the time performed from October to December, and from Carnival to Easter in the public squares of villages and towns. Some companies performed in theaters, or before the court of a European king. For the first time in the history of Italian theater, women performed on stage.

Frequently, actors where paid in food or with lodging. Their hunger was the source of inspiration for their art, turning success into a matter of life and death.

They lived precariously between two lives: one of bliss when performing and the  other of tragedy due to poverty. The structure of the company was always the same: the actors would play the same role for many years, sometimes for their entire life, and the character would retain the same traits. other of tragedy due to poverty. The structure of the company was always the same: the actors would play the same role for many years, sometimes for their entire life, and the character would retain the same traits.

Some actors used masks, mainly the comedic characters. According to the Italian Nobel Prize winner Dario Fo, the use of the mask was for personal safety. Mocking the power of the time was safer when the true identity of the actor was hidden. They lost variety of facial expressions, but gained the freedom to express their thoughts. And at the same time, wearing a mask was a kind of rite, a mysterious veil that set free the Dionysian energy of the character.

Commedia dell' arte is not a dead tradition in theater. It survives through reincarnations in cinema, slapstick, stand up comics, and performances where gesture, movement, rhythm and sound are more important than the words. From Charlie Chaplin to Danny Kayc, and from Buster Keaton to Robin Williams, America keeps commedia in its DNA.

This particular translation attempts to overcome the differences of language by reproducing Goldoni's colourful use of words. The adaptation by Jeff Hatcher and Paolo Emilio Landi places the servant between two brackets of 'reality.' Here we reproduce a typical commedia performance as it may have taken place in a Venetian public square during the middle of the 18th century.

This is a play within a play where theater and its secrets are unveiled to the audience. The two plays are the real life of the company and the play, frequently overlapping and leading to an unexpected ending. Truffaldino strives to overcome the limits of serving two masters, while the actor attempts to overcome his limits as a professional and human being.

The only escape for him, as for us, is art.

|

|