FICTION

THE AUGUSTAN AGE AND THE NOVEL

SAMUEL RICHARDSON: Pamela or Virtue Rewarded

JANE

AUSTEN: Sense and Sensibility

CHARLES

DICKENS: David Copperfield

CHARLOTTE BRONTË: The Woman Question

THE AUGUSTAN AGE AND THE NOVEL

da

Only

Connect vol 1

Da C22 a C32 – THE AUGUSTAN

AGE

C33 THE RISE OF THE NOVEL

Fiction 1 Intro to

fiction as a genre: The Novel, The Short Story

Fiction 2 The Features

of a Narrative text: Setting, Story/plot, Point of View, First-person Narrator,

Characters,

The

commonest form of fiction as a genre is the novel. Fiction comes

from the Latin word fingere; in fact it depicts imaginary events

and characters. However, even though its characters and actions are imaginary,

they are in some sense representative of real life, since they bear an

important resemblance to the real. The novel is written in prose, rather than verse, although a

novel can include very poetic elements

as far as its language is concerned. The novel is a narrative: in other words it is a

telling, it has characters, actions, and

a plot. Finally the novel

involves an investigation of an issue of human significance whose complexity

requires a certain length.

It was in the XVIII century that the novel

as we know it nowadays established itself as an independent and successful

genre, distinct from the prose fiction of the past.

The conditions that favoured

the rise of the new genre were both

social and cultural. Among them were:

. the growth in power — both economic and

political — of the middle classes and their search for a cultural identity and

their need to create for themselves a code of conventions, both social and

literary, distinct from that of the still influential aristocracy;

. the contemporary rise of journalism — The Tatler (1709)

and The Spectator (1711) —

which offered a dignified expression to the needs and aspirations of the

emerging middle-classes.

. the sudden

growth of the reading public and particularly women readers. The growth was due

partly to the diffusion of newspapers, and partly to the increasing affluence

of the middle class, which could now afford many and more expensive books;

. the growing

demand for novels after the creation of circulating libraries. Their moderate

subscription fees increased the number of readers, thus starting continuous

cyclical process of supply and demand;

. the influence of Descartes' and Locke's

philosophical realism which — in the second half of the previous century — had

posited the superiority of the individual experience over tradition and stated

that truth can be achieved by the individual through his senses.

All these conditions favoured

the development of a narrative method which aimed at a realistic

characterization of time, place and characters, and which met the demand of the

middle-classes for a literary genre in which they could recognize their set of

values and their view of the world.

If realism meant

imitation of human life at its average, the first novels pretended to be

authentic accounts of actual human experiences of individuals who had all the

characteristics of their readers.

The 18th- century novelist was

the spokesman of the middle classes; the novel was primarily concerned with

everything that could affect social status and it was mainly directed to a

bourgeois public.

So the plots which

had traditionally formed the backbone of English literature for centuries —

plots taken from history, legend, and mythology — were abandoned. The writer's

primary aim was no longer to satisfy the standards of patrons and the literary

elite, but to write in a simple way in order to be understood even by less

well- educated readers. Since it was the bookseller and not the patron who

rewarded the writer, speed and copiousness became the most important economic

virtues.

The story was

particularly appealing to the practical-minded tradesman, who was self-made and

self-reliant. The writer aimed at realism. The subject of the novel was always

the `bourgeois man' and his problems. He was a definite 'character' and the

hero of the narrative; he was generally the mouthpiece of his author and the

reader was expected to sympathise with him. All the

characters struggled either for survival or social success

The fact that characters were given contemporary names

and surnames was something new and served to reinforce the impression of

realism. The writer was omnipresent and the narrator omniscient, and he never

abandoned his characters.

A chronological sequence of events was generally

adopted by the novelists. Characters seemed to be very much rooted in a

temporal dimension and references were made to particular times of the year or

of the day. Great attention was paid to the setting. In previous fiction the

idea of place had been vague and fragmentary; but in the new novels, specific

references to names of streets and towns, together with detailed descriptions

of interiors, helped render the narrative even more realistic.

THE SETTING

The setting

is the place and the time of the story.

Place setting can be interior or

exterior and it deals with the description of the landscape, interiors and

objects. Time setting usually refers to the time of the day, the season, the

year; but it is important to be aware of the context within which the action of

a novel takes place, so social historical factors are also important.

A narrative

text is made up of a sequence of events, the 'story, that are not always

presented in chronological order. The author can combine them in different ways

using flashbacks, anticipation of events or digressions, or by omitting details

of the story. This original sequence of events is the 'plot'.

NARRATIVE MODES

The author chooses the way to tell his story

using dialogue, description or narration.

Usually these modes are interwoven according to the

writer's aim.

POINT OF VIEW

Suppose you are watching the initial scene of a film in

which a room is the setting. The camera may either take a panoramic view (=

wide angle = obiettivo grandangolare)

of the room or can slowly approach a door (zoom in), get into the room, linger

on some details of the furniture or of the walls and finally take a panoramic

view of the whole room. The camera can be considered to represent the point of

view in a novel.

In the case of the panoramic view of the room, the camera represents the

omniscient narrator's point of view; in the second case it represents the point

of view of a character who has a partial and gradual perception of what

surrounds him/her.

The point of view is, therefore, the angle from which a story or an

episode or any aspect of the fictional reality is presented and narrated. It

can be fixed — in this case it is generally the narrator's point of view —, or

it can shift from the narrator to a character or from one character to another.

It is essential to define the difference between the narrative voice and the point of view.

Read the following examples:

The wind caught the houses with full force.

Paul heard the wind catching the houses with full force.

In both

sentences the narrative voice is the same, but the point of view differs: the

first statement seems to lack a precise point of view, but we may say the point

of view adopted is that of an external

narrator. In the second statement the point of view is Paul's since the

narrator says what Paul hears.

The point of view does not simply refer to the

description or perception of facts and events, but also to their

interpretation. Read these examples:

Mrs Morel was a puritan.

Her husband thought Mrs Morel was a puritan.

Even in this

case the narrative voice is the same, but the point of view differs: in the

first sentence it is the narrator's (narrative voice and point of view

coincide); in the second the point of view adopted belongs to the character of

her husband.

To sum up:

. narrative voice and point of view do not always

coincide;

. the narrative voice belongs to the person who is

speaking, be it an internal or an external narrator;

. the point of view regards the person who, inside the

story, sees the facts, thinks and judges;

. indeed the point of view may vary more often than

the narrative voice.

. The point of view can be fixed and therefore

restricted, or it can be shifting from the narrator's to the character's, or

from one character's to another's, as

often happens in modern fiction.

The

presentation of a character can be 'direct' (through the description which the

writer

makes of his/her personality and appearance) or 'indirect' (when the

reader has to infer the features of the character from his/her actions,

reactions and behaviour). Depending on their role in

the story there can be major and minor characters.

HOW CAN CHARACTERS BE APPREHENTED BY THE READER?

First of all, a character is constituted by a

combination of physical characteristics like height, handsomeness etc. and like

the way he/she dresses; of psychological features like vanity, generosity,

arrogance, prejudice etc. and of social definition in terms of social status

and of social or family relationships with the other characters.

Secondly, a character is sometimes given a name which

focuses on one distinctive aspect of his/her personality. For example in Clarissa Harlowe the

name "Lovelace", which sounds like "without love" or

"unable to love", immediately identifies the character of the

libertine seducer of Clarissa.

Thirdly, a character is given individuality through

the speech and thoughts that the novelist attributes to him/her.

Finally a character performs a role in the structure

of the plot. If he disappeared, the plot itself would be seriously impaired.

Characters and events are the essential elements of

any story and their interaction forms the subiect

matter of any fictional narrative. Their various combinations and the relative

predominance which is assigned to them in turn creates the most remarkable

differences between one novel and another. For example an adventure novel will

privilege action (the events) and will not waste much attention on

psychological characterization.

FLAT CHARACTERS AND ROUND CHARACTERS

A further distinction can be made

between 'round' and 'flat' characters. The former change their personality as

the narration develops and can even influence the plot; the latter do not

change throughout the story and are the so-called 'stereotypes'.

Flat characters are like photographs: they can

be easily recognised because they are always

identical to themselves. They are characterised by

one particular feature, either physical or psychological or linguistic, and

they never change their behaviour or way of speaking,

however the situation may change. They are not subject to evolution. They can

be also called types and they represent the typical in human nature.

Round characters, on the other hand, are

modified by events and in their turn modify events; they have a multiplicity of

features that make them life-like; they grow and evolve in parallel with the

progression of the story.

Da Only Connect

C37 DANIEL DEFOE

C38-39-40 Robinson Crusoe

C47 Moll Flanders

Da Only Connect

C60 SAMUEL RICHARDSON

C61 Pamela or Virtue Rewarded

The term short story is generally applied to almost any kind of fictitious prose

narrative briefer than a novel, capable of being read in one sitting, as Poe

said.

This brief

section analyses the features of the short story as a genre distinct from the

novel. Although length is the obvious distinguishing feature which separates the

novel from the short story, it is by no means the only one. Edgar Allan

Poe, besides writing remarkable short stories, was the first theorist on the

genre.

PARTICULAR

FEATURES OF THE SHORT STORIES

The short story typically limits itself to a brief span of time, and rather

than showing its characters developing and maturing, it shows them at some

revealing moments of crisis, whether internal or external.

Since the

setting is often simplified or circumscribed, much skill of the short-story

writers has to be devoted to rendering atmosphere and situation convincingly.

Very often they will use a key-note to elicit the reader's curiosity and

interest.

Short stories rarely have complex plots; the focus is upon a particular

episode or situation rather than a chain of events. The plot usually develops

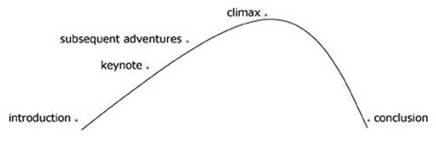

according to a regular pattern:

In the introduction

the author usually presents the setting and the characters.

The key-note

— usually an incident, a crisis or, as often occurs in Poe's tales, an animal

or an object arouses the reader's interest and serves as a catalyst to the

development of the story.

The climax

often comes unexpected and has the function of creating surprise in the reader.

The

conclusion of the story can vary: it can imply a change as regards the initial

situation, the solution of the conflicts, the achievement of the character's

aim, his/her failure or even death; it can re-establish the initial situation;

it can be open, leaving the conflicts unresolved. In this case the

story is meant to continue beyond the limits of fiction.

In about two

centuries, the short story has developed into different forms and many famous

writers have written collections of stories that represent an important step in

their careers, such as James Joyce.

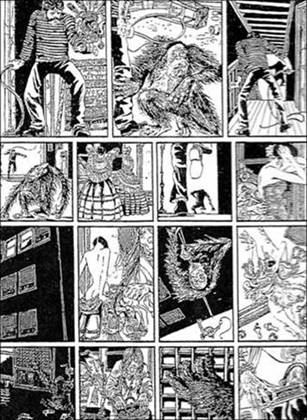

Illustration for The Murders in the Rue Morgue. by Guido Crepax,

1963.

The

fantastic tales of Edgar Allan Poe have inspired illustrations in different artistic

styles, including contemporary cartoons: in the sequence details from the tale

are strikingly highlighted.

THE VICTORIAN COMPROMISE

It is the

period covered by the reign of Victoria (1832-1901).

The particular situation, which

saw prosperity and progress on the one hand, and poverty, ugliness and

injustice on the other, which opposed ethical conformism to corruption, moralism and philanthropy to money and capitalistic

greediness, and which separated private life from public behaviour,

is usually referred to as the "Victorian

Compromise". However, it also aroused the concern of more

and more theorists and reformers who tried to improve living conditions at all

levels, including hospitals, schools and prisons.

The word Victorian has come to be

used to describe a set of moral and sexual values. The Victorians were great moraliser, probably because they faced numerous problems on

such a scale that they felt obliged to advocate certain values which offered

solution or escape. As a rule the values they promoted reflected not the world

as they saw it the harsh social reality around them, but the world as they

would have like it to be.

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

The

Victorians were proud of their welfare, of their good manners and of their

middle-class values, and tended to ignore the problems which still afflicted

England. There was, in fact, a part of society mainly the working class, among

which misery and distress were still widespread. The new urban conditions, made

worse by growth of slums, had created a lot of health problems. Whole families

were often crowded in single rooms, where lack of hygiene occasionally led to

cholera. Poverty, whether the result of bad luck or thoughtless behaviour, was considered a crime and penalized as such.

Debtors, for example, were still punished with jail, and life in prison was

appalling. Education, too, had its problems. Teachers were often incompetent

and corporal punishment was still regularly applied to maintain discipline.

RESPECTABILITY

The idea of respectability distinguished

the middle from the lower class. Respectability was a mixture of both morality

and hypocrisy, severity and conformity to social standards. Manners underwent a

deep change in this period. Under the influence of Queen Victoria herself, the

age turned excessively puritanical. Sex became a taboo subject, and all the

words with vaguely sexual or "indelicate"

connotation were driven out of every day language, or replaced by euphemisms.

Manners and speech were to be retrained and sober, so that "respectability"

became the key word of Victorianism.

THE VICTORIAN

FAMILY

The somewhat conventional

morality the time found its best expression inside the family, where the father

proved even more authoritarian than before and the mother was to be submissive

and fruitful. Victorian families were usually very big and the Queen herself

proved a very prolific mother, with nine children. Middle-class women in

general were to adhere to a strict code of behaviour,

which expected them to be frail and pure, confined within the family walls.

Rules and restrictions involved men too, who were forbidden to gamble, swear or

drink. Appearance being very important, middle-class people's clothes tended to

be very formal even in the privacy of family life.

THE VICTORIAN NOVEL

During the

Victorian Age there was for the first time a communion of interests and

opinions between writers and their readers. One reason for this close

relationship was the enormous growth of the middle classes who, although

consisting of many different strata where literacy had penetrated in a

heterogeneous way, were avid consumers of literature. They borrowed books from

circulating libraries and read the various periodicals, which the age abounded

in. Moreover, Victorian writers often belonged to the middle class.

A great deal

of Victorian literature was first published in this form: essays, verse and

even novels made their first appearance in instalments

in the pages of periodicals, which allowed the writer to feel he was in

constant contact with his public. He was obliged to maintain the interest of

his story at certain levels, because one boring instalment

would cause the public not to buy that periodical anymore; moreover he could

always alter the story, according to its success or failure.

Reviewers also had a strong influence on the

reception of literary works and on the shaping of public opinion.

The

Victorians showed a marked interest in prose, and the greatest literary

achievement of the age is to be found in the novel, which soon became the most

popular form of literature and the main form of entertainment. The spread of

scientific knowledge made the novel realistic and analytical, the spread of

democracy made it social and humanitarian, while the spirit of moral unrest

made it inquisitive and critical.

During the 18th century, novels

generally dealt with the adventures either of a social outcast or a more

virtuous hero, but their episodic structure remained the same.

In the 1840s novelists felt they

had a moral and social responsibility to fulfil: they

aimed at reflecting the social changes that had been in progress for a long

time, Such as the Industrial Revolution, the struggle for democracy and the

growth of towns.

The novelists of the first part

of the Victorian period depicted society as they saw it, and, with the

exception of those sentiments which offended current morals, particularly sex,

no side of it escaped their scrutiny. They were aware of the evils of their

society, such as the terrible conditions of manual workers and the exploitation

of children. However, their criticism was much less radical than that of

contemporary European writers, like Balzac, Flaubert, Turgenev and

Dostoevsky, because the historical conditions of Britain were quite different

from those of France or Russia.

As

the Victorian novelists conceived literature also as a vehicle to correct the

vices and weaknesses of the age, didacticism is one of the main features of

their work. The voice of the omniscient narrator provided a comment on the plot

and erected a rigid barrier between 'right' and 'wrong', light and darkness.

Retribution and punishment were dutifully administered in the final chapter,

where the whole texture of events, adventures, incidents had to be explained and

justified.

The

setting chosen by most Victorian novelists was the city, which was the main

symbol of the industrial civilisation as well as the

expression of anonymous lives and lost identities. In their effort to portray

the individual motives for human action and all that binds men and women to the

community, Victorian writers concentrated on the creation of characters. From

the characters of Dickens's novels, two lines of development arose: the former

moved towards a deeper analysis of the character's inner life; the latter,

typical of later novelists, was nearer to the European development of

'Naturalism', an almost scientific look at human behaviour,

upon which the narrator no longer had power to comment.

JANE AUSTEN:

Life and works

Jane Austen was born in 1775 in a small village in the

southwest of England where her father was rector of the church. The sixth of

seven children, she spent her short, uneventful life within the circle of her

very close, affectionate family, and her lifelong, inseparable companion was

her sister Cassandra who, like Jane, never married.

She was educated at home by her

father, and showed an interest in literature and writing very early. In 1811

she published Sense and Sensibility , in 1813 Pride and

Prejudice and in 1815 Persuasion…

All her novels had been

published anonymously; her identity was revealed by her brother Henry. Jane's

fame, however, was already well established among her contemporaries.

Jane Austen owes much to the 18th-century novelists

from whom she learned the subtleties of the ordinary events of life, like

balls, walks, tea-parties and visits to friends and neighbours.

She restricted her view to the world of the country gentry which she knew best:

"three or four country families", she said, "is the very thing

to work on".

The traditional

values of these families such as property, decorum, money and marriage,

provided the basis of the plots and

settings of her novels.

She writes about the oldest England, based on the possession of land, parks and

country houses; in her stories people from different counties get married as a

result of growing social mobility.

Austen's treatment of love

Austen had no

place for great passions, her real concern was with people, and the analysis of

character and conduct. She remained fully committed to the common sense and

moral principles of the previous generation. Her work is very amusing and, at

the same time, deals with the serious matters of love, marriage, gossip,

flirts, seductions, adulteries and parenthood. The happy ending is a common element to her

novels: they all end in the marriage of hero and heroine. What makes them

interesting is the concentration on the steps through which the protagonists

successfully reach this stage in their lives.

Romantic love gives Jane Austen a

focus where individual values can achieve high definition, usually in conflict

with the social code that encourages marriages for money and social standing.

Her treatment of love and sexual attraction is in line with her general view

that strong impulses and intensely emotional states should be regulated,

controlled and brought to order by private reflection, not in favour of some abstract standard of reason but to fulfil a social obligation.

Sense and Sensibility

The novel is about two two

sisters, Elinor and Marianne Dashwood.

On the death of Mr Henry Dashwood, his estate passes to Mr

John Dashwood. His widow and his three daughters, Elinor, Marianne and Margaret, move to Barton Cottage in

Devonshire at the invitation of a distant relative. There Marianne falls in

love with Willoughby, an attractive young man who seems to share her romantic

tastes. They display their affection openly until he suddenly leaves for

London. Elinor, had become fond of Edward Ferrars, but his

family opposes their engagement because Elinor is not

wealthy. When Elinor and Marianne go to London, they

find out that Willoughby is going to marry an heiress and that Edward has been

secretly engaged to Miss Lucy Steel for five years. After a period of distress,

marked by Marianne's serious illness, the two sisters finally settle down.

Edward goes to Barton to declare that Lucy has broken their engagement and

married his brother. Robert. Elinor and

Edward get married and Marianne eventually becomes the wife of Colonel Brandon,

a family friend who has always admired Marianne.

The title

The title shows the writer's interest in the impulses

that move people to think and behave in certain ways. Elinor's

sense makes her cautious when managing her own affairs and helps her

promote the happiness of her family and friends. Marianne adopts sensibility

as a doctrine which inclines her to artistic enthusiasm, rather than to

sober judgement, and finally exposes her to betrayal

and sorrow.

Characters

Elinor's scrupolous

inner life is the dominant medium of the novel. She represents the author's

conscience and is never a target of irony. It is easy to mistake her sense for

coldness. Actually, through her portrait Austen shows that the complete human

personality needs certain qualities in balanced proportion. Sense and

sensibility; reason and passion complement each other in her. Elinor controls her emotions and regulate her behaviour according to the conventions of society, she

achieves strength and balance of character. Marianne, on the contrary, does not

try to please other people, she refuses to conform. She is lively, sensitive,

intelligent, but she is inclined to rely on first impressions. However, she

gradually acquires sense and settles down by prudent middle-class marriage.

Charles DICKENS: Life and works

Dickens was born in Portsmouth, on the south coast of

England, in 1812. He had an unhappy childhood, since his father went to prison for

debt and he had to work in a factory at the age of twelve. These days of

suffering were to inspire much of the content of his novels. When he realised that he had a talent for writing, he taught

himself shorthand and became a journalist at the Parliament and Law Courts. He

adopted the pen name ‘Boz’

and his Sketches by Boz, a

collection of articles describing London people and scenes, was published in

the "Monthly Magazine" in 1836. It was immediately followed by The

Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, published in instalments,

which demonstrate his humour and satire. Dickens's

success continued with the novels, Oliver Twist (1838), David Copper

field (1849-50), Little Dorrit (1857),

which drew on his own childhood, and his journalism. He exposed the exploited

lives of children

in the slums and factories. Other novels include Bleak

House (1853), Hard Times (1854) and Great Expectations (1860-61).

These novels are set against the background of social issues, highlighting the

conditions of the poor and the working class.

He was also the busy editor of magazines,

"Household Words" and later "All The Year Round" which

published not only his own work but the writings of other novelists. He spent

his last years travelling round giving theatrical readings of his own work. He

died in 1870 and was buried in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey.

The plots of

Dickens's novels

Dickens was first and foremost a storyteller. His

novels were influenced by the Bible, fairy tales, fables and nursery rhymes, by

the 18th-century novelists and essayists, and by Gothic novels. His plots are

well-planned even if at times they sound a bit artificial, sentimental, and

episodic. Certainly the conditions of publication in monthly or weeldy instalments discouraged

unified plotting and created pressure on Dickens to conform to the public

taste.

London was the setting of most of his novels: he knew

and described it in realistic details. At first, Dickens created middle class

characters, though often satirised. He gradually

developed a more radical social view although he was not a revolutionary

thinker. He was aware of the spiritual and material corruption under the impact

of industrialism and he became increasingly critical of society. In his mature works Dickens succeeded in drawing popular attention to public abuses, evils

and wrongs by juxtaposing terrible descriptions of London misery and crime with

amusing sketches of the town.

Characters

Dickens created caricatures. He exaggerated and ridiculed the peculiar social characteristics

of the middle, lower and lowest classes, using their own voices and dialogue.

His female characters, were weak, and black and white. He was always on the

side of the poor and the outcast, and shifted the social frontiers of the

novel: the 18th-century realistic upper middle-class world was replaced by the

one of the lower orders.

A didactic aim

Children are often the most important characters in

Dickens's novels. By giving instances of good children and worthless parents or

hypocritical adults he reverses, in fiction, the natural order of things, by

making children the moral teachers instead of the taught, the examples instead

of the imitators. The novelist's ability lay both in making his readers love

his children, and putting them forward as models of the way people ought to

behave to one another. This didactic stance was very effective, since the

result was that the more educated, the wealthier classes throughout England

acquired a knowledge of their poorer neighbours of which

many were previously ignorant. Dickens's task was never to induce revolution,

or even encourage discontent, but to get the common intelligence of the

country, in all its different classes alike, to alleviate undeniable

sufferings.

Style and reputation

For these purposes he employed the most effective

language and accomplished the most graphic and powerful descriptions of life

and character ever attempted by any novelist, by means of a careful choice of

adjectives, repetitions of words and structures, juxtapositions of images and

ideas, hyperbolic and ironic remarks.

Fictions of

the City

To read Dickens is to encounter an urban writer whose

work does not only rely on the city for the setting of plot and character, but

rather situates London at the centre of his fictions: it is the generator of

plot and the determining element of scene and setting. In describing this

London, he makes it our living presence.

Dickens's representations of lower-class life echo those

of journalists of his time.

Oliver

Twist - Plot

Oliver Twist first appeared in instalments in 1837 and was later published as a book. The

novel fictionalizes the economic insecurity and humiliation Dickens experienced

when he was a boy.

The name Twist, though it is given to the protagonist

by accident, represents the outrageous reversals of fortune that he will

experience. Oliver Twist is a poor boy of unknown parents; he is brought up in

a workhouse in an inhuman way. He is later sold to an undertaker as an

apprentice, but the cruelty and the unhappiness he experiences with his new

master get him to run away to London. There he falls into the hands of a nasty

gang of young pickpockets, who try to make a thief out of him, but the boy is

helped by an old gentleman. Oliver is eventually kidnapped by the gang and

forced to commit burglary; during the job he is shot and wounded. It is a

middle-class family that adopts Oliver and shows kindness and affection towards

him, at last. Investigations are made about who the boy is and it is discovered

he has noble origins. The gang of pickpockets and Oliver's half-brother, who

paid the thieves in order to ruin Oliver and have their father's property all

for himself, are arrested in the end.

London's life

The most important setting of the novel is London,

which is depicted at three different social levels. First, the parochial world

of the workhouse is revealed. The inhabitants of this world, belonging to the lower-middle-class

stratum of society, are calculating and insensible to the feelings of the poor.

Second, the criminal world is described with pickpockets and murderers. Poverty

drives them to crime and the weapon they use to achieve their end is violence.

They live in dirty, squalid slums with fear and generally die a miserable

death. Finally, the world of the Victorian middle-class is presented. In this

world live respectable people who show a regard for moral values and believe in

the principle of human dignity.

The world of the

workhouse

Dickens attacked the social evils of his times such as

poor houses, unjust courts, and the underworld. With the rise in the level of

poverty, workhouses run by parishes sprang up all over England to give relief

to the poor. However, the conditions prevailing in the workhouses were

appalling. Their residents were subject to a host of hard regulations: labour was required, families were almost always separated,

and rations of food and clothing were meagre. The

idea upon which the workhouses were founded was that poverty was the

consequence of laziness and that the dreadful conditions in the workhouse would

inspire the poor to get better their own conditions. Yet the economic

dislocation of the Industrial Revolution made it impossible for many to do so,

and the workhouses did not provide any means for social or economic

improvement. Furthermore, as Dickens points out, instead of alleviating the

sufferings of the poor, the officials who ran workhouses, abused their rights as

individuals and caused them further misery.

David Copperfield Plot

David

Copperfield is David's narration in his maturity of the events and

incidents through which he remembers his life. The protagonist's recollections can

be divided into three main parts:

- his childhood and early youth, starting with his

birth in Blunderstone and ending when he completes

his time at Strong's school in Canterbury (chapters 1-18);

- his later youth and early manhood, from looking for

a career to the death of his first wife, Dora;

-

his maturity, starting from his mourning for Dora and ending with his marriage

to Agnes Wickfield and happy life afterwards.

Born a posthumous child to an immature and ineffectual

mother, Clara Copperfield, David starts life in a state of happiness with his

mother and his nurse, Peggotty. This condition is

destroyed by the arrival of his cruel stepfather, Mr Murdstone, and his sister Jane. Eventually they drive Clara

to an early grave because of their terrible 'firmness'. David is, then sent

away to Salem House, a school far from home; here he is tormented and brutalised by Mr Crealde, the harsh, cruel headmaster. After his mother's

death, he is consigned to Murdstone and Grinsby's wine warehouse in London where he works,

experiencing poverty, despair and loneliness. He lives with the family of Mr Micawber, whose continual

financial difficulties lead to his eventual imprisonment for debt.

Running

away from this fate, David decides to reach his aunt Betsey in Dover. In spite

of her eccentricity, she makes him grow up and dismisses the Murdstones from their responsibility for him. David

concludes his education and looks for a career in London, where he starts to

work at first as Doctor Strong's secretary and then as a parliamentary

reporter. Later he becomes a successful writer, but he makes a disastrous

marriage with Dora Spenlow, loses his inheritance

from Aunt Betsey and is betrayed by his closest friend.

It

is only at the very end of the novel, after his first wife's death and his own

symbolic death and rebirth, that he marries his predestined love, Agnes Wickfield, and lives happily ever after.

Narrative technique

David Copperfield is

a Bildungsroman, that is a novel that

follows the development of the hero from childhood into adulthood, through a

troubled quest for identity. The emotional identification of Dickens with David

is very strong; trivial clues, like the use of his own initials in reverse, are

interwoven into a more straightforward identification of careers. David, like

Dickens, is a parliamentary reporter who becomes a literary man. By speaking in

thefirst person, the author enjoyed all the pleasures

of sentimental reminiscence. The protagonist of the novel functions also as

narrator and the book is built as a fictional autobiography. David is never

offstage: all the events and characters are revealed through his presence and

consciousness.

The characters of the novel are both realistic and

romantic; they are exaggerated, like all Dickens's figures, and characterised by a particular psychological trait, which

can be a particular way of speaking, of moving and behaving.

Main themes

The first chapters of David Copper-field introduce

the main themes of the whole novel:

- the struggle of the weak in society: David is

an orphan and a victim, he stands for the uncertainty, the loneliness and the

terrible evanescence which characterised the life of

those people who were not helped by a cruel, competitive society;

- the great importance given by the respectable Victorians

to strict education based on hard and physical punishment;

-

cruelty to children who were exploited by the adults;

-

the bad living conditions of the poor who lived in slums;

- the

importance of social status: after a hard childhood David succeeds in improving

his social condition thanks to his determination and perseverance.

-

friendship and love leading to marriage.

Is David a hero?

The first five paragraphs raise a central question

which is whether we are to regard David as the hero of the novel. The answer is

both yes and no. David is not a hero in the ordinary sense of the term, since

he is not an example of integrity who either by brave actions or spiritual

strength defeats the forces of evil. In fact, his lack

of discipline, romanticism

and self-deception

· lead him to disaster. However he can be called a hero because he learns, through experience and suffering, how to improve his character and his circumstances. Realism and enchantment

·

The pervading atmosphere of the novel is a combination

of realism and

·

enchantment. There is an apparent realism in the

people, places and events of the story, but those protagonists are also imbued

with the magic of a fairy tale.

·

The Murdstones enter the

scene like ogres; they fade away like a nightmare. Even Betsey Trotwood is in

the tradition of the fairy godmother, omnipotent, wilful

and kind. She has no human need to conform (not reflexive) to reality. All her

prejudices are treated as admirable. Peggotty's

brother's house belongs to fairytale and so does the account of the death of

her husband, Barkis, who suddenly disappears.

·

Uriah Heep, Wickfield's clerk, is a villain, a strange, repellent,

sinister creature, unable to smile. Uriah hates David because David is the

embodiment of what he might have been; on the other hand, David's attraction to

Uriah is the human attraction to evil. By distorting reality and fantasy,

Dickens helps us grasp reality and sharpen our awareness and knowledge of the

external world.

·

Throughout the book, there is no real pressure of

reality, no logic of cause and effect. David, employed in a wine warehouse,

needs a kind relative, money and education. He finds them. David wishes to

marry Dora against her father's consent; so Dora's father suddenly dies. Dora

is the type of feather-brained beauty who is only tolerable when she is young,

and David needs to escape to the safe arms of his good angel, Agnes. So Dora

too dies. Difficulties and dangers disappear like mist; and their main function

seems to give that quickened sense of joy and relief which follows their

miraculous removal.

Charlotte BRONTË – Life - Jane Eyre

Jane is a penniless orphan, brought up at Gateshead

by her cold and

hostile aunt, Mrs Reed. Jane is then sent to Lowood Institution, a

very strict school, where girls are not given enough food and clothing. When she grows up she becomes a teacher there but finally

she decides to accept a job as a governess at Thornfield Hall where she soon falls in love with Mr Rochester,

its owner. Her stay at the Hall is disturbed by strange noises and frightening

events.

The traditional 'Gothic' convention is used, but in a

personal way, from childhood terrors to all those mysterious and threatening sights and sounds that reveal the presence of some malevolent force and

that anticipate the tragedy at Thornfield.

With Charlotte’s

limited knowledge of the world, it should come as no surprise that the plot of

her first published novel, Jane Eyre, contains many parallels to her own life.

Regardless of her intentions while writing Jane Eyre, it is clear that

Charlotte Brontë drew heavily on her own identity and

experiences in creating the character of Jane.

Jane Eyre’s childhood

seems in some respects to have been modeled after Brontë’s.

Like Charlotte herself, Jane’s father was “a poor clergyman” .

Jane’s

parents both died when she was a baby; whereas Charlotte’s

father outlived all his children, their mother died when Charlotte was five

years old. After Mrs. Brontë’s death, her unmarried

sister, Elizabeth Branwell, moved in with the family

to care for the six Brontë children. The parallels

between Aunt Branwell and Mrs. Reed continue into

adulthood.

Some parts of Jane Eyre’s childhood were taken directly from Charlotte Brontë’s memories; no matter how extreme seem the

conditions of Lowood, the school is, in fact,

intentionally modeled after Charlotte’s own experiences at Cowan Bridge.

The

relationship between Jane and her employer, Mr. Rochester, may have also been

suggested by events in Charlotte’s own life. During her stay in Brussels,

Charlotte apparently fell in love with M. Heger, who

was first her teacher, and then her employer, as she

accepted a teaching position at the school at the end of her studies there.

That

Charlotte Brontë drew on her own limited life

experiences in the creation of Jane Eyre is demonstrated by the many parallels

between Charlotte’s life and her heroine’s. Jane evinces many of the characteristics

of her creator, to the point that Jane Eyre is a portrait of Charlotte herself.

It is clear that Charlotte Brontë put not only her

heart and soul into her writing, but her very life.

After spending some time at her

aunt's deathbed, Jane returns to Thornfield and Rochester

proposes to her. She agrees to marry him,

but two nights before the wedding she

wakes up and sees a figure standing by her

bed and her wedding veil torn into two pieces. The wedding is interrupted by Richard Mason who

declares that Rochester is already married to his sister Bertha Mason, a mad woman he married in the West Indies and who lives on the upper floor of the house,

looked after by Grace Poole. Rochester asks Jane to stay with him, but she leaves Thornfield

and goes to live with her cousins at

Moor House. There she meets St. John Rivers,

a religious man who plans to become a missionary and proposes to her.

Jane refuses and one night she hears

Rochester's voice calling her; she returns

to Thornfield Hall only to find out that the house has been destroyed by a fire caused by

Bertha, who then threw herself

downstairs and died. Mr Rochester lost an eye and a hand in the attempt

to save his wife from the fire; he now lives in Ferndean.

Jane visits him and agrees to marry him. He finally recovers his sight just when their first child is born.

Mode of narration

The novel shows the consequences of childhood experience in the fully-grown character, and draws largely upon the author's own experience at the

Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan

Bridge, and at the Pensionnat Heger

in Brussels, where Charlotte fell in love with Mr

Heger but was not reciprocated.

The use of the heroine as narrator is mainly responsible for the peculiar unity of Jane

Eyre. All is seen from the point of view of the central character, with whose experience the author has identified herself, and invited the engagement of every

reader. Jane continually occupies the centre, never receding into the role of mere reflector or observer. She

gains awareness not by long

introspection but by a habit of keeping

pace with her own experience.

The story is told in the first person and the popularity

of Jane Eyre as a subject for feminist criticism has in large part been

due to its employment of a female first-person narrator. The language is straightforward and develops differently according to the style and

mood of each character. This emotional use

of language conveys the author's concern with the nature of human relationships. There are also

repeated motifs, symbols, and images: the workings of

the supernatural, important dreams, patterns of light and dark, oppositions of

warmth and cold.

A

woman's standpoint

From the day of its appearance Jane

Eyre has been credited with having added something new to the tradition of the English novel. The new quality is the voice of a woman who speaks with perfect frankness

about herself; but Jane Eyre is also remarkable

for its passion and intensity, which is usually taken as sufficient to counteract what critics regard as

a sensational and poorly constructed plot.

The novel described passionate love from a woman's

standpoint in a way that shocked many

readers. The public preferred women to be presented with something of the unreality of romance; above all the heroine should be

beautiful and rich. Jane Eyre is

moderately plain, and this made her

very real; moreover, she falls in love with a man both rich and married

to a mad wife.

Each section of the novel represents a new phase in

Jane's experience and development. The protagonist's

character is developed very clearly: she is intense, imaginative,

passionate, rebellious, independent yet always looking for warmth and affection. She undergoes many struggles such as

the conflicts between spirit and flesh, duty and desire, denial and fulfilment.

The novel also establishes the theme

of the outsider, the free spirit fighting for recognition and

self-respect in the face of rejection by a

class-ridden and money-oriented society.

A

new perspective on characters

Even Jane is portrayed so as to evoke new feelings. As

a girl she is lonely, 'passionate',

'strange’ she experiences a nervous

breakdown; she can be ‘reckless and

feverish'; at Thornfield she is restless, given to

'bright visions'. However, she is also strong-willed and responsible for her

own decisions, like the final one to be Rochester's wife, which she tells the

reader directly: "Reader, I married him."

So the author leads away from conventional characterisation towards new insights of human reality. In

Rochester the old lustful villain is seen in a new perspective: (…) the

stereotyped seducer becomes a kind of lost nobleman of passion who is attracted

by Jane's soul and personality rather than by physical appearance.

Women

are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they

need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as

their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a

stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their

more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves

to making puddings….knitting stockings….playing on the piano….It is thoughtless

to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than

custom has pronounced necessary for their sex.-Ch. 12

The Woman Question

The Victorian period lasted more than half a century. During this time

England changed radically in almost all respects. One of these was the rising

consciousness of women about their rights and potentials. For

the first time in English history, women became conscious of their capabilities

and their rights. Soon, the social

awareness was transmitted to literature. It was during the Victorian era

that a series of changes - social, political and moral - swept all over

England. One of these concerned the issues of gender inequality in politics,

economic life, education and social intercourse for women known as the ‘Woman

Question’. Within a few years it gained momentum and became just as grave an

issue as evolution or industrialization.

With the

spread of education and the contribution of the printing press, which reduced

the cost of books greatly, the nineteenth century became the great age of the

English novel, partly because the novel was the vehicle best equipped to

present a picture of life and this is the kind of picture of life the middle

class reader wanted to read about. Literature became the mirror of society.

The only

woman in the political arena at the time was Queen Victoria who considered

women’s suffrage (although as a ‘crazy idea’). Thus for a long time women

remained second class citizens from the political point of view, along with

millions of working class men. They finally attained the right to vote in 1918.

In addition

to parliamentary reforms the feminists worked hard to enlarge educational

opportunities for women. In 1837 none of England’s universities was open to

women. By the end of the reign of Queen Victoria, women could take degrees at

twelve universities and could study without earning a degree at Oxford and

Cambridge. But before that, education for women was available only in schools

such as Lowood School in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

A large

number of women remained unmarried because of the imbalance between the number

of men and women in the Victorian population. Having few employment

opportunities and due to bad working conditions, many of these women were

driven to prostitution. The only employment option for a middle-class Victorian

woman, to earn a living, was to be employed as a governess.

In this

socio-literary background, female writers - like Jane Austen, the three Brontë sisters and many others - choose as their female

protagonists, women who would represent their thoughts and attitudes and that

prefer capability to beauty. Charlotte makes Jane intentionally unattractive

and not much gifted. But from the very first moment we meet the sickly, unloved

child we are attracted by her love of reading.

When

Rochester, failing to marry Jane legally, proposes to her to become his

mistress, she not only refuses but also resigns her position in his house and

finds another situation. This capacity to take responsibility in adverse

situations was one of the chief features which gained women the rights they

wished for. She later marries him when he is physically and financially reduced

by the accident which kills his wife. Many readers were shocked that Rochester,

who tried to make Jane his mistress, should be rewarded by marrying her. Some

readers were also shocked because Jane wanted to be regarded as a thinking and

independent person rather than a weak female. But here we must consider the fact

that Rochester’s love for Jane was genuine, as she was neither attractive, nor

able to pay a dowry, nor eligible for a man in his position when he first

proposed to her.

Charlotte Brontë and her sisters, in spite of living deep in the

bleak and barren Yorkshire moors, surprised the world by the consciousness,

expressed in their work, of the ‘Woman Question’. They have won a permanent

place in English literature by dint of the power and intensity of their work.

The sisters

used their masculine pseudonyms. Almost all female writers of the period

thought it fit to assume disguises in presenting themselves to the world as

novelists. Thus, their anonymity was never officially broken during their

lifetime. An opportunity for women in the late Victorian period was a career as

a novelist. Besides that, there was the advantage of maintaining anonymity

which made writing an attractive option for women who wanted to achieve

something without exposing themselves to the criticism of society.

In retrospect we find that many women writers emerged to achieve their

rights and to be given an opportunity to come out of the shells of quiet

submission enforced upon them and achieve something of their own.

The best way

to pay tribute to the predecessors of so many women who enjoy freedom all over

the world today, is to go forward maintaining those moral and social bindings

which once helped the Victorian women to break out of male tyranny and yet earn

their respect.

NB la versione read – print – ePub* del romanzo Jane Eyre si trova

presso:

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/bronte/charlotte/

* leggere sempre

le note relative al copyright

Fonti:

Spiazzi

Tavelli Only Connect Zanichelli

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Cody, David. Charlotte Brontë: A Brief Biography. 27

Nov 2004. Hartwick College.

Evans, Barbara and Gareth Lloyd. The Scribner Companion to the Brontës. New York:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1982.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë.

1857. 27 Nov. 2004.

http://lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/EG-Charlotte.html

Everett, Glenn. A Charlotte Brontë Chronology. 27

Nov. 2004. University of Tennessee

at Martin. 1987.

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/brontetl.html.

Miller, Lucasta. The Brontë

Myth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001.

Nestor, Pauline. Charlotte Brontë. Totowa, New

Jersey: Barnes & Noble Books, 1987.

Peters, Maureen. An Enigma of Brontës. New York: St.

Martin’s Press, 1974.

Joan Douglas Peters Feminist Metafiction and

the Evolution ofthe British Novel University of

Florida

Daiches, David (1969), A Critical

History of English Literature, London, Secker and Warburg,

Volume IV, p 1064- 1065-1066

The Norton Anthology of English Literature (1993), New York, W.W. Norton

and Company

Inc; Volume 2, p 902

14. ibid, p 1595

Basu, Nitish

Kumar (1998), Advanced Literary Essays, Calcutta, Presto Publishers, p

315

Traversi, Derek (1996),

The Bronte Sisters and Wuthering Heights, The New Pelican Guide to

English Literature, Edited by Boris Ford, London, Penguin Group, Volume

6, p 250

World Book Encyclopedia (1996), Chicago, World Book Inc., Volume B, p 587

Handley, Graham (1987), Introduction, Wuthering Heights, London,

Macmillan Education

Ltd., p xviii