ARUNDO DONAX: THE SOURCE OF NATURAL WOODWIND

REED

Marilyn S. Veselack

Editor's Note: This article

summarizes the presentation the author gave at the reed seminar at the Los

Angeles conference of IDRS. Ms Veselack is a candidate for the Doctor of

Arts degree at Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana. The studies

outlined in the article were done in the laboratory of Jerry J. Nisbet.

The Arundo plant (Arundo donax L.

) has been of significance to the various cultures of the Western world

because of its role in the development of music. This plant is also known

as Giant reed or Persian reed. It is indigenous to the areas surrounding

the Mediterranean Sea. Later it was cultivated and naturalized in the

warmer climatic regions of every major continent.

Scientifically, Arundo donax L.

belongs to a tribe of the extensive grass family Gramineae. It is

sometimes confused with bamboo, which differs in many internal structural

features. In its outward appearance Arundo resembles giant corn, having

stems that grow from four to six meters in height. The stem is very hard

and some of the epidermal cells contain silica, which is the same thing as

glass. Jaffrey reports that one can understand the hardness of this plant

from noting that a stem of a mature reed gives off sparks when it is hit

with an axe. Although the stem is hard, the sparks originate when the

metal of the axe strikes the silica. The Arundo stems are unique in their

ability to recover quickly from flexing. No other plant material can match

its natural spring and ability to recover from fatigue.

During World War II, the reed fields of

France were cut so that large mats could be woven from the stems and

leaves for use in aerial camouflage by the military. This process depleted

the source of maturing reed stems. As a consequence, the reed supplies for

musicians could not be replaced with mature reed material at the rate that

was needed to fill the demand.

Jaffrey recommends that the stems can

begin to be harvested after they have hardened sufficiently and turned a

golden yellow. The correct hardness may be attained after five to eight

years' growth, while strength and color may require from ten to twenty

years. If the stems are cut at a very early age, they will shrink to a

mere shell when dry. If cut at a later age, but prior to maturity, the

stems have a tendency to warp.

In accordance with pre-World War II

practices, mature stems were stored for a period of one to three years of

natural curing, prior to being used for the manufacture of woodwind reeds.

Prior to World War II, only three out of every forty harvested Arundo

stems were acceptable for manufacturing reeds. After World War II reed

companies were forced to practice little or no selectivity, and nearly all

available stems were used for manufacturing woodwind reeds. Woodwind

players found themselves faced with the problem of being able to use only

two to five reeds from every twenty-five reeds manufactured after World

War II.

Beginning in the early 1940's woodwind

musicians became aware of the need to experiment with and to study the

reed. Persons who have studied a particular aspect of the reed problem

state that their efforts are stymied by a lack of willingness to

communicate among musicians and scientists. The most serious deterrent to

investigating the reed problem was and still remains the task of bridging

the communication gap between music and science. The breakdown is brought

about by misunderstandings and differences in meanings of terms used by

each area of specialization.

I have been studying the cell structure

and characteristics of the mature stem of Arundo donax with the

view of identifying possible differences in stem anatomy, which may be

related to the quality of woodwind reeds. To acquire material for the

study, clarinet reeds were obtained that had been used in performance and

judged playable by forty knowledgeable musicians. The same musicians were

also asked to supply clarinet reeds which they judged to be non-playable.

Twenty-one of the musicians were professional clarinetists from twenty-one

major symphony orchestras in the United States. Eleven were musicians

associated with colleges and universities in the United States.

In preparing the material for study, the

heel end of the reed is sawed into small blocks. The central blocks of

tissue from each reed are softened by chemical treatments and embedded in

paraffin. The central blocks of tissue are used because they contain all

the cell types and cell arrangements typical of that part of the stem used

for clarinet and other woodwind reeds.

Squares of paraffin containing the

suspended reed material are attached to specimen holders and sliced into

10 micron sections. A micron is 1 /25,000 of an inch. A sheet of typing

paper is approximately 100 microns thick. The sections cut with the

microtome form a ribbon, which is transferred to microscope slides. The

paraffin is removed by a solvent and the sections are stained to increase

the visibility or contrast in tissues when examined under the microscope.

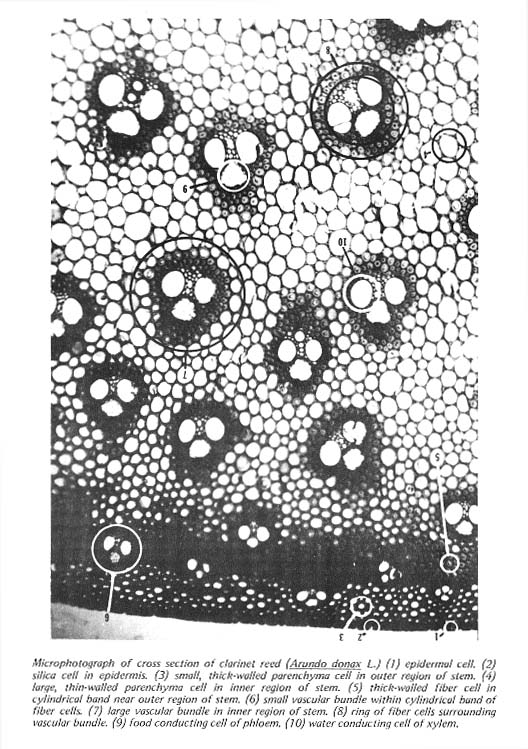

In the cross section of reed, the

epidermis shows a regular pattern of normal epidermal cells which are

small and thick walled interspersed with clear oval-shaped silica cells.

Several layers of parenchyma cells are found immediately under the

epidermis. In this region the parenchyma cells are relatively small and

thick walled in contrast to the large thin walled parenchyma cells found

in the inner region of the stem.

A band of fiber cells is located inside

the cylinder of small parenchyma cells. This band of fiber cells is

continuous around the stem and separates the outer stem tissues from the

inner tissues.

Vascular bundles are scattered

throughout the stem in a pattern very similar to that found in corn and

other members of the grass family. Very small vascular bundles are found

close to the surface of the stem. The size of the bundles increases toward

the center. Each vascular bundle consists of a ring of fiber cells

surrounding the xylem and phloem. The vascular bundles are what the

woodwind musician refers to as the "fiber" or "grain"

of the reed.

Stems in a more mature state of

development have more parenchyma cells with very thick walls. Fiber cells

also develop extremely thick walls with age.

The heel of a reed contains all of the

kinds of cells of the Arundo plant and woodwind reed. The blade of a

woodwind reed contains only parenchyma cells and vascular bundles. The

tapering cut made in the shaping of the reed removes all of the epidermal

cells and the underlying band of fiber cells from the reed blade. However,

all of the cells--both those in the heel as well as those in the blade--

contribute to the vibrational characteristics of the reed. When the

clarinet is played, the reed blade vibrates against the mouthpiece at

frequencies of 147 to 1,568 cycles per second. The quality of sound

produced by a reed depends in large measure upon the stage of development

of the Arundo stem at the time of harvesting.

As the Arundo stem grows older, the

thickness of the cell walls increases. Following harvesting of the Arundo

stems, a lengthy period of seasoning is required during which time fluids

in the cells slowly dry up.

Apparently much Arundo is currently

being harvested after only a few years of growth and the stems are

artificially dried for a period of a few weeks or months prior to being

used for the manufacture of woodwind reeds.

Aside from selecting reeds with uniform

distribution of vascular bundles, the musician can enhance the playability

of reeds by adjusting them to fit his or her specific mouthpiece/embouchure

combination. However, even when such adjustments are made, the most

obvious variable in performance with a good woodwind instrument is still

the reed. The majority of woodwind teachers and performers agree that the

quality of the reed material is a fundamental determining factor affecting

the playability of woodwind reeds.

Related Literature

Bhosys, Waldemar. "The Reed Problem."

Woodwind Magazine, 1948, 1(2), 4 and 8.

--------. "The Reed Problem." Woodwind

Magazine, 1949, 7(3), 5 and 8.

Christlieb, Don. Notes On The

Bassoon Reed. California: Don Christlieb, 1966.

Jaffrey, K. S. Reed Mastery.

Australia: K. S. Jaffrey, 1956.

Kotzin, Ezra. "The Reed Problem".

Woodwind Magazine, 1948, 1(1), 4.

Nederveen, C. J. "Influence of Reed

Motion On The Resonance Frequency of Reed-Blown Woodwind Instruments".

JASA, 1969, 45(2), 513-514.

Patterson, John. "An Experiment In

Growing And Curing Reed Cane (ARUNDO DONAX) In Louisiana". 16th

National Conference Yearbook Of College Band Directors National

Association, 1971, 152-153.

Perdue, Robert E., Jr. "Arundo

donax Source of Musical Reeds And Industrial Cellulose". Economic

Botany, 1958, 12, 368-404.

Waln, George E. "How To 'Raise

Cane' ". The Instrumentalist, 1961, XV(7), 56-60.

Williams, Alexander. "Reed Problem".

Woodwind Magazine, 1949, 1(4), 5-6.

|